Askeladden Capital letter to investors for the second quarter ended June 30, 2019. titled, “Askeladden Reloaded.”

Dear Partners,

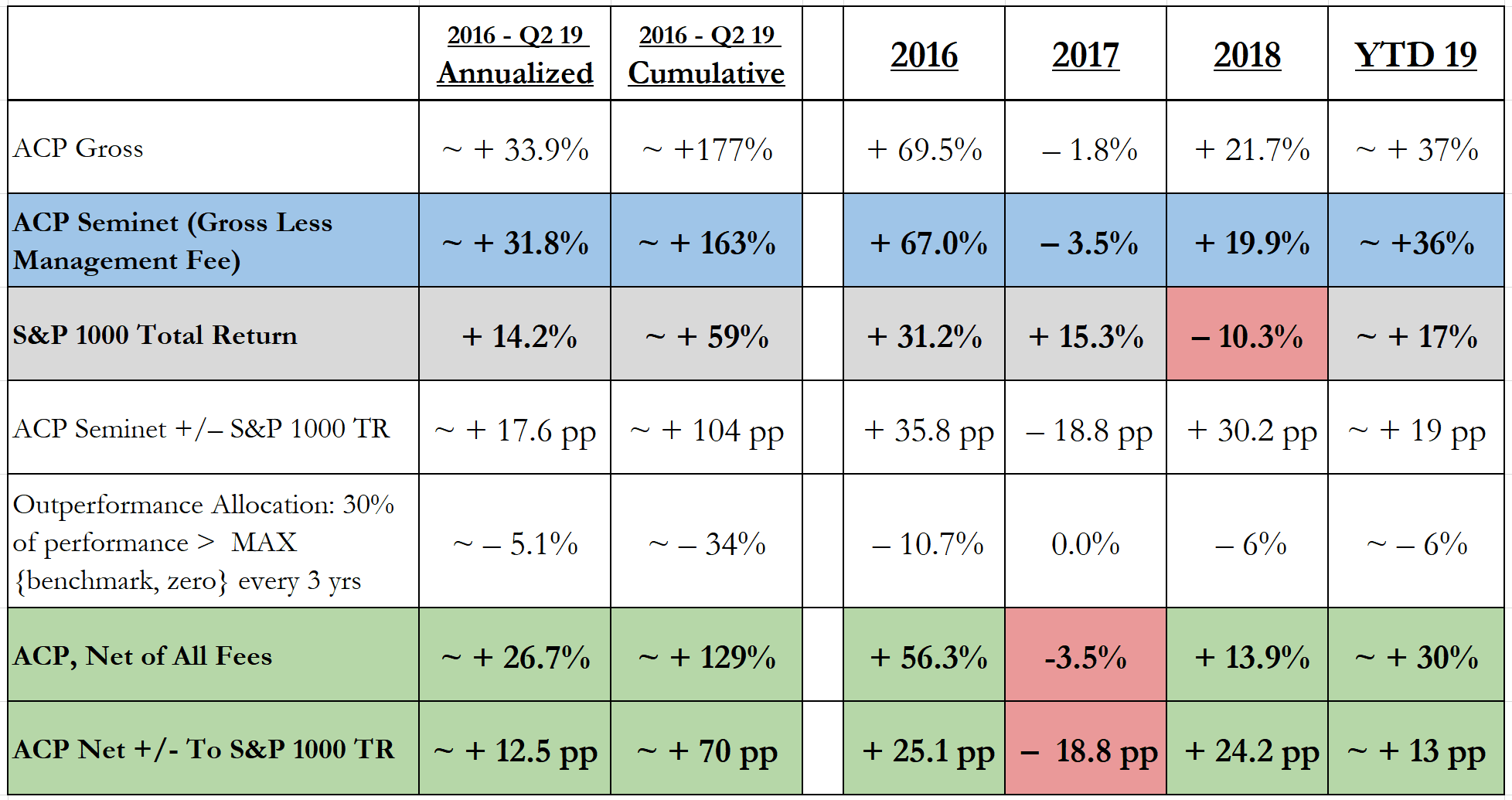

Year to date through 6/28/2019, Askeladden Capital Partners LP has returned in excess of ~ +37% gross, representing a positive spread of over 20 percentage points compared to the +17% return of our benchmark, the S&P 1000 Total Return. This brings our cumulative gross performance in the ~3.5 years since inception to ~ +177%, compared to benchmark performance of +59%.

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

On an annualized basis, returns since inception have been ~ +33.9% (gross) and ~ +26.7% (net), compared to benchmark performance of +14.2%. In light of our material outperformance over the past three years, the first outperformance allocations from a client account are due and payable this month and next.

Given the portfolio outlook, I am not withdrawing a single cent, and have instructed our fund administrators to roll the entire (low-mid-five-figure) balance of outperformance allocations to my LP account on the appropriate dates. Pro forma for this, roughly 70% of my investable (ex-cash) net worth will be held in Askeladden Capital Partners LP, with the balance in stocks held by the fund.

Across the fund and SMAs, actual fee-paying AUM as of 6/28/2019 exceeds $9 million, triple what it was less than a year ago, and meaningfully above last quarter. All of this capital was raised organically, mostly from people who first encountered me by reading a letter on the internet just like this one.

Given the long sales cycle for institutional investors, conversations sparked by the efforts of our third-party marketer Maury McCoy have not yet translated into capital. This is par for the course; Maury had the same experience when he was working with Brian Bares (who now manages billions of dollars.) When Maury’s efforts translate into capital, it will likely be with a far larger initial check than we typically get.

As usual, we have a number of clients in the process of signing up or contributing additional funds. Based solely on committed capital (not “prospects”), I would anticipate FPAUM exceeding $10 million by year-end. Of note, our clients (as well as prospective clients) now include numerous family offices and high net worth individuals who seem likely to substantially increase their allocation to Askeladden over time. I believe that we could easily exceed $20MM of FPAUM within a few years solely based on our existing client base.

On the next page, you will find the standard performance chart, with the appropriate disclaimers. Please see the appendix for additional important disclaimers. Please also remember that we do not use leverage or options; we are a long-only plain-vanilla small-cap equity shop. Our portfolio tends to be comprised of either good businesses at great prices, or great businesses at good prices – we have not participated in FAANG, cryptocurrency, or other such areas that have been popular (and high-return) since our inception. We run a classic, cash-flow oriented value portfolio; we buy when things are cheap and sell when they’re not.

In the balance of the letter, there are two topics I wish to convey:

1) How our watchlist process has enabled us to quickly “reload” the portfolio and maintain a robust (mid-twenties) three-year forward expected annualized return, despite substantial gains year to date.

Roughly 47% of our portfolio is allocated to companies we have followed for at least three years, with an additional 11% and 20% allocated to companies we have followed for at least two years and one year. This substantially reduces “familiarity risk” – most of the positions we own and are adding to are companies we have followed longitudinally, observing and learning patiently for quarters or years before turning them into meaningful positions.

2) Our evolving views on concentration/diversification (we now hold 15 stocks, with the largest position being merely 22% and the next four positions, in aggregate, representing 35% exposure.)

Do It Now, Remember It Later

Echoes of songs still lurk on distant foreign shores, where we

Danced just to please the gods… who only asked for more

And so it goes.

But still we give... ourselves to this

Can’t spend our lives waiting to live.

- “The Dirt Whispered” by Rise Against

In the investment management world, clients don’t care about how good your performance was last year, or for the trailing five years. Those might be inputs into their decision to invest new or additional capital with a manager - but they’re the equivalent of sunk costs. They’re in the past.

If you’ve made money, all clients care about is the future. It’s not your trailing three year track record that matters, but the forward three year returns. What have you done for me lately?

This is not a complaint, nor a premature sense of jadedness (I pride myself on being an optimist and have little tolerance for cynics or nihilists.) It’s simply the nature of reality in the profession that I have chosen. It’s not irrational behavior by clients; it’s reasonable behavior. There are many investment alternatives; continuing to hold a suboptimal one represents a large opportunity cost.

I don’t continue to hold stocks that I don’t think will generate superior returns, so I understand and appreciate why clients would not want to continue to hold investments with managers that they do not think will generate superior returns.

As such, I don’t want to talk extensively about past performance when it’s good. Past performance is done and gone. There will come a day where I look back at my track record and celebrate my success.

But today is not that day, because my track record is just getting started. Beating the market isn’t cause for celebration. It’s my job. There’s a reason these letters are signed with “westward on.” It’s a callback to Howard Schultz’s “Onward.” Ever forward, with a sprinkle of American exceptionalism. Manifest destiny.

Beating my own chest serves no purpose except contributing to a cascade of (negative) cognitive biases. So instead, I want to talk about future performance, and what I’m doing to maximize our chances of achieving an acceptable result over the next three years.

Askeladden, Reloaded

There is something I’m proud of right now, but it’s not, per-se, our trailing performance. Rather, it’s our expected future performance.

For a while now (I don’t remember exactly how long), I’ve had a cell on my portfolio-management spreadsheet called “CAGR.” This is a sum-product weighted expected return for our portfolio. There is, of course, no guarantee that such a return will be achieved; I’d like to stress that this is merely a portfolio-management KPI that I use, rather than any sort of explicit forecast about future returns (which are inherently unknowable and unpredictable.)

For each company in our portfolio and on our watchlist, I have an underwritten fair value estimate, i.e. the price at which the stock would be fairly-valued, using conservative estimates and a 10% equity discount rate.

From that estimate, and the market price, one can come up with a simple three-year forward return expectation, assuming that the stock trades at my estimate of fair value in three years’ time. The formula is:

CAGR = { [ (1.1 ^ 3) * (Fair Value) ] / Current Stock Price } ^ 0.3333 – 1

Of course, this is just a number. My assumptions may be wildly wrong. Even if they’re right, I have not, to the best of my recollection, had a stock trade at exactly my fair value estimate for more than a few seconds. Timing is variable, too – sometimes things rerate more quickly than three years; sometimes it may take longer.

So this number isn’t some sort of magical dictum from the investing gods; it’s just a number. But it does have a use – the higher the number, the higher our likely future returns are, assuming my underwritten assumptions are correct.

All things being equal, we want a higher number. A higher number means a higher probability of higher future returns. On an individual stock level, our CAGR number helps us think about whether it’s worth selling one holding to buy another. On the portfolio level, the number helps us determine whether our process is successfully generating suitable investment candidates.

Considering that my underwriting threshold is 20% annualized returns over a three-year period, the current figure – 24.1% – is quite robust, especially considering that we’ve had ~ +37% gains year to date and are at a high water mark for NAV (i.e. we’re at an all-time high, not recovering from any deep hole). 24% is not the highest figure we have ever seen (the number was above 30 during the December selloff last year), but it’s still a very good one. To translate it into more everyday terms, if actual returns meet or exceed this threshold, then it would take about three years and one quarter to double our capital.

An adjustment should be made, however. The number was above 26% a few days ago, prior to Franklin Covey Co. (NYSE:FC) reporting strong earnings. On the price strength, we trimmed our position some, leaving us with a cash balance in the 4 – 5% range. We intend to deploy at least some of this cash over the coming weeks and months, and on an ex-cash deployed-capital basis, the current CAGR is 25.3%.

Many funds would be in a challenging position after a + 37% first half of the year. In many cases, they would either be sitting on a lot of not-deeply-discounted stocks, presaging lower future returns – or they would have trimmed or sold these positions, thus being underinvested and ending up in the same predicament.

How have we managed to maintain such a robust forward returns outlook? The answer is our differentiated watchlist process, which I have discussed extensively before. When I launched Askeladden, my thesis was that building a watchlist of quality businesses would allow us to consistently identify good businesses at great prices, or great businesses at good prices.

In tangible terms, we today have a watchlist of 140 companies that we are intrigued by for one reason or another; we can build a portfolio of 15 companies from the 28 stocks in the lowest valuation quintile, picking and choosing based on qualitative factors (such as our affinity for the business and its management team, risk factors such as cyclicality and leverage, etc.)

Statistically speaking, some stocks will always be out of favor / overlooked / etc; it’s in fact quite surprising how often we look up to see yesterday’s high-flying growth darlings trading at a bargain-basement valuation to their cash flow. Sprouts (SFM) and Duluth Trading (DLTH) used to trade at multiples we’d never touch with a ten-foot pole, but today they’re classic value stocks at low-double-digit multiples to steady-state free cash flow – despite long, long runways for accretive capital reinvestment and capital-free comp growth. They, like the overwhelming majority of what we own, have a long history of compounding value per share.

So rather than trying to spend our time looking at what’s cheap today – in the process not developing any long-term IP, and also spending a lot of time sorting through crappy businesses – we prefer to build a database of business we like and rely on the statistical likelihood that some fraction of them will be compelling at any given time. We like compounders; we just don’t like typical “compounder” multiples.

We own 15 stocks today, but the watchlist – excluding companies that we’ve hidden for various reasons (i.e. we’re not interested in owning them at this time, but might be in the future) – offers us 22 companies with 20% or greater expected three-year CAGRs. The watchlist further offers 11 companies with 15 – 20% expected three-year CAGRs, many of which we haven’t looked at in a while – meaning that some of them could very well meet our expected returns threshold.

When our portfolio is essentially fully allocated, our focus (other than on monitoring portfolio positions) is to add new names to the watchlist. More names = a better statistical chance of owning the intersection of quality and value. Moreover, as has been frequently discussed in the past, following businesses longitudinally over time helps build a more nuanced understanding than trying to learn about them all at once.

Unlike a screener that surfaces cheap stocks with no regards for quality, our watchlist surfaces good businesses that we already understand very well and have followed for quarters or even years. In other words, it tees up great investment opportunities that are right in our sweet spot. And it will only get better over time as the breadth (number of companies) and depth (number of updates on existing companies) continues to increase.

It’s a simple process, but one that I believe provides us with a sustainable source of alpha for several reasons.

First, a substantial portion of the watchlist is comprised of stocks that we believe are too small to attract serious attention from larger funds; more than half of the watchlist is comprised of sub-$1B stocks, with a third comprised of sub-$500MM stocks and a fifth comprised of sub-$300MM stocks. Given that we are closing to new capital at $50MM and plan to continue compounding organically to somewhere in the $100MM - $200MM range, we will always be able to invest in such stocks, unlike many of our peers.

Second, just because there is no physical moat around a business process does not mean that it is trivial to replicate. As former Sprouts CEO Amin Maredia observed at an investment conference several years ago:

Every format you walk in and it always looks like it's easy to emulate or copy. We can all walk into Chik-fil-A right now and go, how hard is this? But it is, right? And it's really something we've built over 20 years that's special.

This rang true to me: while there are many examples we’ve seen (LGI Homes atop the list), the one that will resonate best with most readers is Chipotle. It seems deceptively simple: how hard is it to put out thirty boxes of ingredients and let patrons pick what they want on their burrito?

But despite the vast abundance of capital in the restaurant sector (there is no shortage of new restaurants), I cannot think of many concepts that have managed to execute a Chipotle-like model at scale. Remember when everyone got excited about Pie Five after a spiffy presentation at ICR? Anyone?

Our watchlist and research documentation process is like that – easy to describe; very hard to execute.

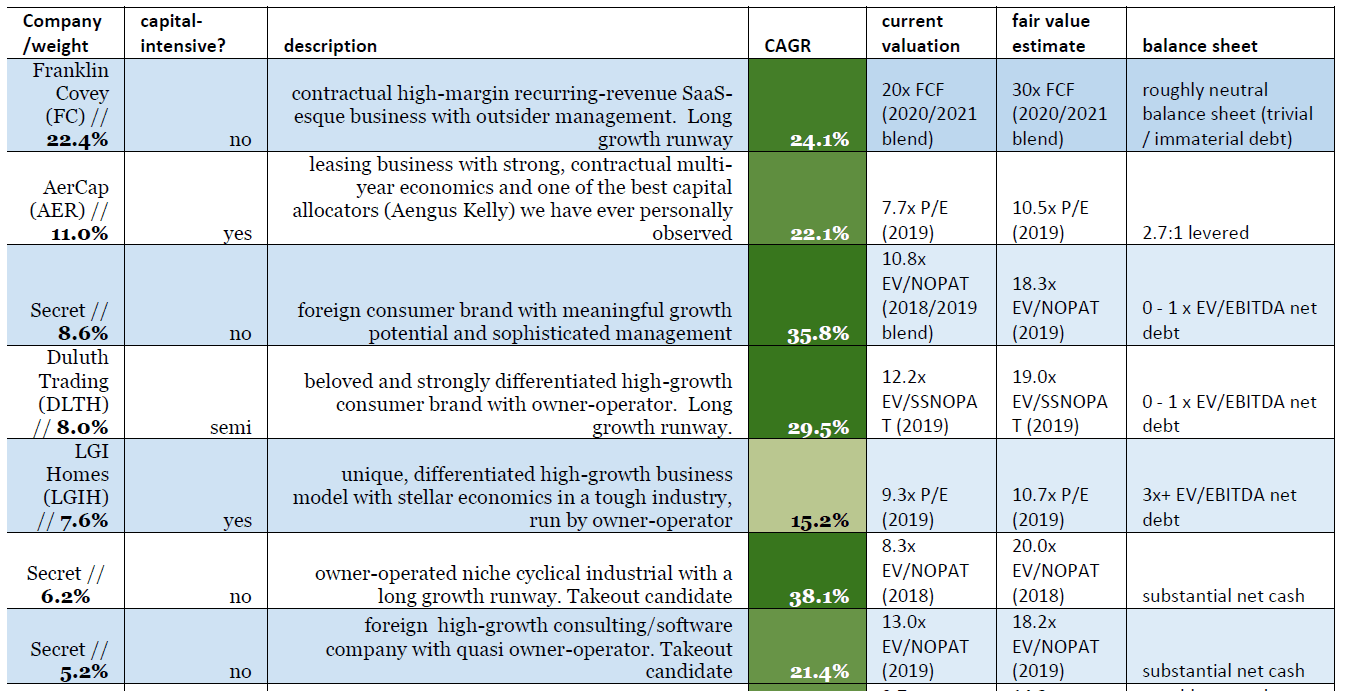

Enough theory. On the next page is a redacted table overviewing what we own (clients have access to the unredacted director’s cut in the separately-delivered 19-page quarterly portfolio commentary.)

Observe that we own a portfolio of generally modest to high growth businesses, with a skew towards owner-operators, with conservative balance sheets – most of which, with a few exceptions, trade no higher than a low-teens EV/NOPAT multiple, and some of which trade for single-digit EV/NOPAT multiples. We’re not sacrificing quality for price; we can have both at the same time because of our differentiated approach. Our portfolio is the equivalent of the produce section at Sprouts.

One thing to note here, again, is that “CAGR” is just a number. It is not the only decision metric we use. For example, purely on the basis of expected return, one could ask why we don’t sell some Franklin Covey (FC) and AerCap Holdings N.V. (NYSE:AER) to buy other, higher-return names, such as the two 8 – 9% positions.

There’s a simple reason for this: FC and AER stand head and shoulders above most of the rest of our portfolio with extremely low-risk business models and management teams for which we have extremely high regard and trust. Both Franklin Covey and AerCap are highly insulated from economic volatility and near-term competitive pressures, as they have multi-year contracts with locked-in profitability; said differently, unless their counterparties default en masse (extremely unlikely in both cases), then any negative variances vis-a-vis our expectations of their earnings should be modest, notwithstanding the macro.

No matter what happens in the world, we are very confident that Franklin Covey and AerCap will continue to have steady, predictable, and very profitable results. Moreover, both companies have a history of aggressively repurchasing shares, so any dips in the share price would result in higher long-term returns for shareholders.

Conversely, some of the still-large but smaller positions - while very attractive - have their own idiosyncratic risks, such as the competitive environment, or exposure to consumer spending that might partially (though not severely) dry up in a downturn.

Our goal is to run an all-weather portfolio; eschewing all leverage and consumer discretionary risk means foregoing plenty of quite-attractive opportunities that can provide great returns - and at a certain cash flow multiple, these businesses are often priced for “trough” earnings anyway (i.e., we have a big enough margin of safety to endure a challenging economic environment and still make money.)

On the other hand, of course, it would be unpleasant (not to mention overly-risky) to only own such businesses; having now seen hundreds of companies deliver probably thousands of earnings reports, I’ve come to appreciate the “no surprises” results that come with a business with contractually recurring revenue, vis-a-vis businesses that have to start each year with zero in revenue.

Some Thoughts on Concentration and Diversification

I’ve always maintained that hyper-concentration was more a temporary rather than permanent phenomenon; I’m not sure anyone believed me, but I have pretty consistently told existing and prospective clients, since inception, that running the fund with a 30%+ position was not what I intended to do on a continual basis – it simply seemed like the appropriate response to having a disproportionately attractive, extremely high-return and low-risk investment opportunity (most recently, Franklin Covey in the low $20s.)

Beyond this, I’ve also always maintained that running a sub-10 stock portfolio was not what I intended to do; it’s just where I found myself sometimes because I didn’t see enough breadth of opportunities to justify replacing allocations to stocks 1 – 7 with allocations to stocks 8 – 15. Today, that’s not the case, and – while it is always difficult to make forecasts, especially about the future – I would anticipate running closer to the higher than lower end of our targeted 10 – 15 stock portfolio.

There are several reasons for this. The first is that as I’ve matured as a portfolio manager, I have realized how silly some of the dictums oft-repeated by value investors are. For example, low turnover to the exclusion of all else is a dumb goal. As one of our clients – a professional investor himself – quips, “you really want to buy stocks that go up really fast, then sell them to buy other stocks that go up really fast.”

There are merits to tax sensitivity, familiarity with and affinity for the business, etc, which I do consider, but those can be incorporated without changing the thrust of the point – it’s silly to lock ourselves in to owning businesses for three years just because we underwrite for three years; if we buy something we think is worth $10 for $7, and a few months later we look up and see it’s trading for $9.50, it makes total sense to trim or liquidate the position and redeploy the proceeds into another 70-cent dollar from our watchlist.

There is actually a data-driven reason we are discussing this. Our experience has not necessarily suggested that our largest positions are always the biggest IRRs; while that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be the largest positions (as other considerations, such as invisible risk borne, are important too), the fact remains that every year, we’ve had some small positions skyrocket, and disproportionately contribute to returns.

Looking over trade records, here is some data – please note that I’m not sure if I’m capturing commissions in these numbers, but they would be completely immaterial to the scope of the discussion:

- We purchased a small position in MiX Telematics (MIXT) in May 2017 at a cost basis of $6.05. Between June and December 2017, we liquidated this position at a weighted price of $9.82 – a 60%+ premium to our purchase price. I’m too lazy to calculate per-lot IRR, but obviously, earning 60% in half a year is a very good outcome.

- Also in 2017, we purchased a small position in tiny Canadian home-security company AlarmForce (AF.TO). This position was established at a cost basis of $9.90 in September 2017; the company was acquired for a 60% premium later that year, and we sold our position for $15.99 per share in November 2017.

- In early 2018, we purchased a small position in Dynamic Materials / DMC Global (BOOM), paying an average of $22.81 per share. Although we loved the company, given their exposure to oil prices, and our other energy exposure in the portfolio, we did not feel it was appropriate to make the position very large. As the market reacted positively to strong earnings, we liquidated the position between April and July at an average price of $42.05 per share, or a premium of over 80% in, again, less than half a year.

- At the end of February 2018, we purchased a small position in high-margin recurring-revenue software company Zix (ZIXI), paying an average price of $3.95 per share. The market quickly realized that the business was better than the multiple, and before the company had even reported its next earnings report, we were able to liquidate our position for $4.89 – a gain of over 20% in merely a couple months. (ZIXI, today, trades for over $9 per share, for what it’s worth.)

- In mid to late 2018, as well as early 2019, we purchased shares in niche software company Globalscape (GSB). Focusing solely on our higher-cost purchases in 2019, we purchased shares on March 1st for $5.86 per share. Over the ensuing four months, we have entirely liquidated the position at prices between $7.39 and $10.04, with a weighted average of $9.11. Again, I’m too lazy to calculate IRR, but the point remains that we earned a 50%+ return in a short timeframe.

- Finally, in December 2018, we put on a tiny (and I mean really tiny, I think it was 20 bps) position in telematics company Pointer Telocation (PNTR) at a cost basis in the low $12s. A quarter later in mid-March, the company announced it was being acquired, and we liquidated our position in the high $15s – again, a greater than 20% gain in a very short time period.

There are a few other examples we have excluded for brevity. Admittedly it’s a small sample size, but the point here is that sometimes really good things happen to stocks really quickly, and they’re not really predictable ex ante – yet we seem to get at least one quick pop per year from a smaller position. Conversely, of course, we’ve had large positions like FC – that ended up working out well! – languish for quite some time.

Although we’re not trying to optimize for short-term performance, having more shots on goal seems like the best way to maximize our chances of getting some quick wins as well as more methodical, longer-term returns. I’ve always believed that if the returns expectations are the same and the risks not materially different, more positions are better than less all things equal, and as the watchlist has gotten larger, we’ve gotten more and more opportunities – I find it increasingly difficult to state categorically that 10 or fewer stocks are infinitely superior to all other opportunities we see, such that we should only own 8 stocks.

A second consideration is risk. With extremely large positions, there is obviously elevated risk that a single wrong assessment by me would materially impair returns; compounding this issue, it is far easier to get emotionally involved in large positions than in small ones – creating the potential for behavioral errors such as commitment bias / change blindness, etc. Conversely, nobody gets too attached to sub-500 bps positions.

One of the things I think I’ve improved on the most is having emotional distance between me and the portfolio; when I started Askeladden, I was definitely emotionally invested in my investment theses – today, that is the case much less frequently; I feel more like a dispassionate observer than a cheerleader. I’m much more willing to cut a position and move on, whether or not the position is showing a gain. It’s the difference between watching a sports game when you’re not a fan of either team, and when you are a fan of the team – you make far more objective judgments when you’re not rooting for either side.

Of course, there are tradeoffs here; for example, we are probably taking modestly more cyclical risk today than we would be if I simply put more money in Franklin Covey, AerCap, and several other non-cyclical positions. On balance, though, I still think the portfolio is lower-risk for the incremental diversification.

Importantly, I think there are limits. Empirical evidence is often quoted suggesting that the benefits of diversification tail off quickly beyond 15-20 stocks. More practically, as a one-man shop with an intensive research process, it’s simply not practical to run a 20 – 30 stock portfolio – all my time would be spent monitoring the portfolio, and so any benefits of diversification (or otherwise) would be offset by having less research time available to spend on identifying new opportunities.

Ultimately, while I’m not changing my targeted 10 – 15 stock range – and would be perfectly comfortable running a 10 stock portfolio – I do feel a preference for the higher end of the range (i.e., 12 to 15 stocks.) Please note that I would also be perfectly comfortable with a 16 – 17 stock portfolio, under the assumption that some of those stocks were close (but not all the way) to monetization.

Conclusions

We have been extremely fortunate to have such strong results over the past 3.5 years. While these returns are clearly unsustainable, I’m still very optimistic about being able to achieve superior returns over time – which is why I continue to deploy sizable chunks of my own capital into the fund as it becomes available.

We have also been extremely fortunate to have a base of long-term, value-oriented clients who understand our process. We have a heavy skew towards investment professionals, which is gratifying – many of our clients are current or former professional investors, whether that means active management or another area of the financial world (such as wealth management.)

Three and a half years ago, I launched Askeladden Capital with no paying clients, hoping it would turn into a sustainable business. While I’m never going to be a master of the universe, I am now the master of my own destiny – Askeladden has enough clients and business momentum to support a modest but comfortable lifestyle, and proprietary intellectual property that positions us well to continue generating strong results.

Westward on.

Samir

This article first appeared on ValueWalk Premium