U.S. multinationals have been at the forefront of the golden era of globalization, building out some of the most extensive supply chains in the world to their competitive advantage. However, the tide of globalization is in retreat, and the pendulum is swinging back toward protectionism, populism and nationalism. Escalating trade tensions not only portend weaker global growth and added market volatility near term but also a long-term rethink among multinationals on how to do business on a global scale.

What do investors need to know as the global supply chain starts to unwind? Joe Quinlan, head of CIO Market Strategy for Merrill and Bank of America Private Bank, says one of the main beneficiaries will be automation – or advanced robotics, artificial intelligence, additive manufacturing (3-D printing), digital platforms and related activities geared towards the ability to suppress costs, boost margins and nimbly reach more-demanding consumers.

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Moreover, despite higher relative U.S. labor costs, he sees the U.S. emerging as one of the most attractive places in the world for investment, particularly new greenfield investment among foreign investors.

The Golden Era for Multinationals is Over-Now What?

For decades, the world was their oyster. China’s “opening” to the West in 1979; the collapse of Communism in 1989; sweeping economic reforms in India in 1991; the creation of the European Single Market in 1992; the passage of the North America Free Trade Agreement in 1994; the European Union “enlargement” to 28 member states earlier this century—all of these seminal events helped forge a golden era for U.S. multinationals.

So did the spread of globalization—or unfettered cross-border flows of capital, goods, ideas, people and data—which knitted more and more nations into the fabric of the global economy, giving multinationals access to more resources, more workers and more consumers. One key upshot: rising earnings from abroad, with Rest of World profits of American firms rising by over 250% since the start of the century, or 6.9% annualized.

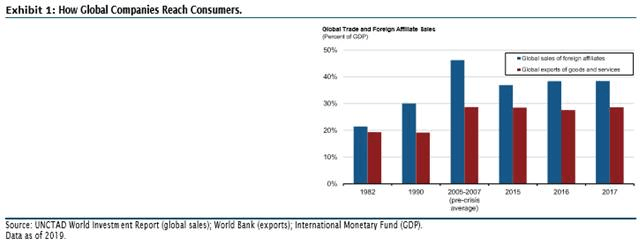

Falling transportation and communication costs also helped to grease the wheels of global commerce, allowing U.S. firms to operate virtually any place in the world. With American firms in the forefront, global foreign direct investment outflows have soared over the past few decades, rising from an annual average of just $47 billion over 1980–85 to an estimated $1.2 trillion last year. The more the investment, the more the trade, with global trade regularly outpacing the rate of global growth for decades. In turn, the combination of rising trade and investment has meant thicker and more complicated global supply chains and the rise of foreign affiliates as the main conduit for global commerce. Think of the latter as foot soldiers of globalization. They are at the core of any global supply chain—and key cogs in the financial success of any multinational. They are also the bedrock of the global economy.

According to the latest figures from the United Nations, the total assets of all foreign affiliates in the world topped a staggering $100 trillion in 2017, with total affiliate output (value added) in excess of $7.3 trillion, a figure well in excess of the aggregate output of the world’s largest economies, save China and the U.S. Affiliates employed over 73 million workers worldwide in 2017, while sales of affiliates were nearly $31 trillion. Affiliate sales were some 34% larger than global exports of goods and services in 2017, and accounted for roughly 38% of world GDP versus 29% for global exports (Exhibit 1).

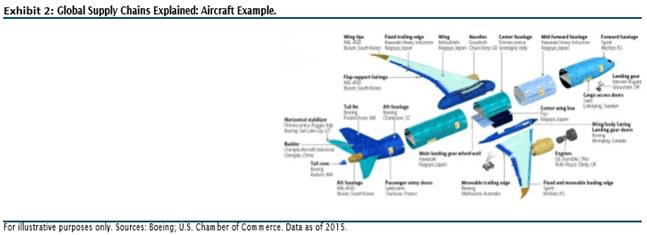

Underscoring the importance of foreign affiliates to U.S. multinationals, sales of affiliates totaled an estimated $6.9 trillion in 2018, almost three times larger than U.S. exports. [1] With more than 37,000 foreign affiliates scattered around the world—from Albania to Zimbabwe— U.S. multinationals have been at the forefront of the golden era of globalization, building out some of the most extensive and thickest supply chains in the world to their competitive advantage. As a real world example of a global supply chain—in this case Boeing—take a look at Exhibit 2, which underscores the complexity and global scale of building/assembling an aircraft.

However, given all of the above, times are changing. The days of U.S. multinationals being largely unbound are over. The tide of globalization is in retreat. To the disadvantage of many firms operating outside their own borders, nationalism and populism are on the rise around the world. Rather than being seamless, the world is becoming balkanized or fragmented, which is another way of saying that the golden era for multinationals is history.

The past won’t be the prologue, so what now?

It’s a new world for multinationals. Forty years of declining tariffs and non-tariff barriers, and relatively open borders that allowed companies to disaggregate production around the world, is reversing. The pendulum is swinging back toward protectionism, populism and nationalism, all of which are inimical to globalization and existing global supply chains of multinationals. Escalating trade tensions between the U.S. and China—in addition to friction with Mexico, India and Europe—not only portend weaker global growth and added market volatility near term but also a long-term rethink among multinationals on how to do business on a global scale.

Complex, multinational supply chains are under review and are likely to be gradually unwound in the years ahead. Where for the past four decades global manufacturing operations of firms were geographically diffuse, with plants spread across borders and reliant on a network of international suppliers, future operations will be more local and regional in scope. Think less ‘offshoring’ of production and a movement to ‘re-shore’ or ‘near-shore’ – that is, for U.S. firms to perform more of their manufacturing closer to home—a la Tijuana, Mexico or Toledo, Ohio. Given the ongoing spat with Mexico, the latter looks more attractive.

The U.S. is hardly the cheapest place in the world to manufacture, but higher relative U.S. labor costs will be offset by increased automation, greater supply chain mobility, lower shipping costs and very competitive energy costs thanks to the American energy renaissance. Add in tax reform and other government incentives like job training credits and favorable treatment of capex spending, in addition to a large and wealthy consumer, market, and the U.S. emerges as one of the most attractive places in the world for investment. (As a footnote, and as we recently highlighted, the U.S. ranked first in terms of new greenfield investment among foreign investors in 2018).[2]

Who wins?

One of the main beneficiaries around the rethink and reconfiguration of global supply chains will be automation, in our opinion—or advanced robotics, artificial intelligence, additive manufacturing (3-D printing), digital platforms and related activities geared towards the ability to suppress costs, boost margins and nimbly reach more-demanding consumers. Yes, lower-cost locales like Vietnam, Cambodia and perhaps Mexico will see a rise in foreign direct investment. But the attractiveness of these nations will be offset by the rapid adoption of robotics and related activities, the next advancements in 3-D printing, and the growing penchant among multinationals to shorten and simplify their global supply chains, and “build where they sell.”

U.S. firms bringing their supply chain closer to home will allow them to better serve the end consumer in two main ways. The first is simply by granting them more flexibility to respond to new orders and to reduce delivery times. But second, and perhaps more important, is by improving their product offering via better-integrated research & development (R&D). Housing manufacturing alongside core activities such as design, marketing and product development, the argument goes, should help to spur innovation, increasing responsiveness to shifts in consumer preferences and boosting competitiveness and profitability in the process.

Among sectors, robotic manufacturers should stand to gain as global robotic penetration accelerates not only in the U.S. and the developed nations but also in the emerging world, notably China. The mainland is already one of the largest users in the world of robots and will maintain this position as it adopts to the new world order in trade and rising wage costs at home.

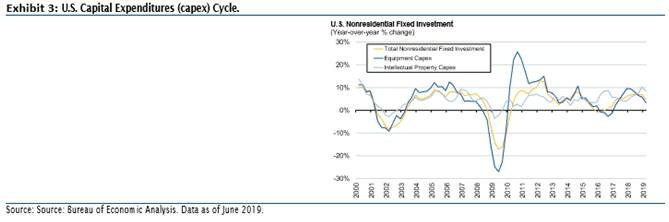

Although the U.S. capex cycle has recently lost momentum (Exhibit 3), we believe that demand for robotics and AI/data-driven production processes among multinationals is a secular trend that should help boost investments in capital equipment and intellectual property products (i.e., software, R&D spending) over the long run. This shift toward more automated manufacturing provides an important buying opportunity for long-term investors considering building exposure in leading global robotics companies.

Important Disclosures

This material was prepared by the Chief Investment Office (CIO) and is not a publication of BofA Merrill Lynch Global Research. The views expressed are those of the CIO only and are subject to change. This information should not be construed as investment advice. It is presented for information purposes only and is not intended to be either a specific offer by any Merrill or Bank of America entity to sell or provide, or a specific invitation for a consumer to apply for, any particular retail financial product or service that may be available.

Global Wealth & Investment Management (GWIM) is a division of Bank of America Corporation. The Chief Investment Office, which provides investment strategies, due diligence, portfolio construction guidance and wealth management solutions for GWIM clients, is part of the Investment Solutions Group (ISG) of GWIM.

Bank of America, Merrill, their affiliates, and advisors do not provide legal, tax, or accounting advice. Clients should consult their legal and/or tax advisors before making any financial decisions.

Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

All recommendations must be considered in the context of an individual investor’s goals, time horizon, liquidity needs and risk tolerance. Not all recommendations will be suitable for all investors. Asset allocation, diversification and rebalancing do not ensure a profit or protect against loss in declining markets.

Investments have varying degrees of risk. Some of the risks involved with equity securities include the possibility that the value of the stocks may fluctuate in response to events specific to the companies or markets, as well as economic, political or social events in the U.S. or abroad. Small cap and mid cap companies pose special risks, including possible illiquidity and greater price volatility than funds consisting of larger, more established companies. Bonds are subject to interest rate, inflation and credit risks. Municipal securities can be significantly affected by political changes as well as uncertainties in the municipal market related to taxation, legislative changes, or the rights of municipal security holders. Income from investing in municipal bonds is generally exempt from Federal and state taxes for residents of the issuing state. While the interest income is tax-exempt, any capital gains distributed are taxable to the investor. Income for some investors may be subject to the Federal Alternative Minimum Tax. Investing in lowergrade debt securities (“junk” bonds) may be subject to greater market fluctuations and risk of loss of income and principal than securities in higher rated categories. Treasury bills are less volatile than longer-term fixed income securities and are guaranteed as to timely payment of principal and interest by the U.S. government. Mortgage-backed securities are subject to credit risk and the risk that the mortgages will be prepaid, so that portfolio management may be faced with replenishing the portfolio in a possibly disadvantageous interest rate environment. Investments in foreign securities (including ADRs) involve special risks, including foreign currency risk and the possibility of substantial volatility due to adverse political, economic or other developments. These risks are magnified for investments made in emerging markets. Investments in a certain industry or sector may pose additional risk due to lack of diversification and sector concentration. Investments in real estate securities can be subject to fluctuations in the value of the underlying properties, the effect of economic conditions on real estate values, changes in interest rates, and risk related to renting properties, such as rental defaults. There are special risks associated with an investment in commodities, including market price fluctuations, regulatory changes, interest rate changes, credit risk, economic changes and the impact of adverse political or financial factors.

Companies may reduce or eliminate dividend payment to shareholders. Historically, dividends make up a large percentage of stocks’ total return.

Nonfinancial assets, such as closely-held businesses, real estate, oil, gas and mineral properties, and timber, farm and ranch land, are complex in nature and involve risks including total loss of value. Special risk considerations include natural events (for example, earthquakes or fires), complex tax considerations, and lack of liquidity. Nonfinancial assets are not suitable for all investors.

Investments in tangible assets are highly volatile and are speculative. There are special risks associated with an investment in commodities, including market price fluctuations, regulatory changes, interest rate changes, credit risk, economic changes, and the impact of adverse political or financial factors.

Alternative investments such as derivatives, hedge funds, private equity funds, and funds of funds can result in higher return potential but also higher loss potential. Changes in economic conditions or other circumstances may adversely affect your investments. Before you invest in alternative investments, you should consider your overall financial situation, how much money you have to invest, your need for liquidity, and your tolerance for risk. Alternative investments are speculative and involve a high degree of risk. An investor could lose all or a substantial amount of his or her investment. There is no secondary market nor is one expected to develop and there may be restrictions on transferring fund investments. Alternative investments may be leveraged and performance may be volatile. Alternative investments have high fees and expenses that reduce returns and are generally subject to less regulation than the public markets. The information provided does not constitute an offer to purchase any security or investment or any other advice.

Bank of America Private Bank is a division of Bank of America, N.A., Member FDIC, and a wholly-owned subsidiary of Bank of America Corporation (“BofA Corp.”). Trust and fiduciary services and other banking products are provided by wholly-owned banking affiliates of BofA Corp., including Bank of America, N.A.

© 2019 Bank of America Corporation. All rights reserved

[1] Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, total sales of all foreign affiliates. [2] See Capital Market Outlook, May 20, 2019, “Global Greenfield Investment: America is First.”