The search for extraterrestrial life continues even after the Kepler space telescope is no longer in operation. Now new research has revealed 18 new Earth-sized exoplanets, which are planets located outside our solar system. They weren’t uncovered until now because they aren’t big enough to be detected in previous surveys.

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS), the Georg August University of Göttingen, and the Sonneberg Observatory uncovered the 18 new Earth-sized exoplanets. While one of the planets is too small to have the conditions humanity would need to survive, the largest could offer an environment that’s to that of Earth.

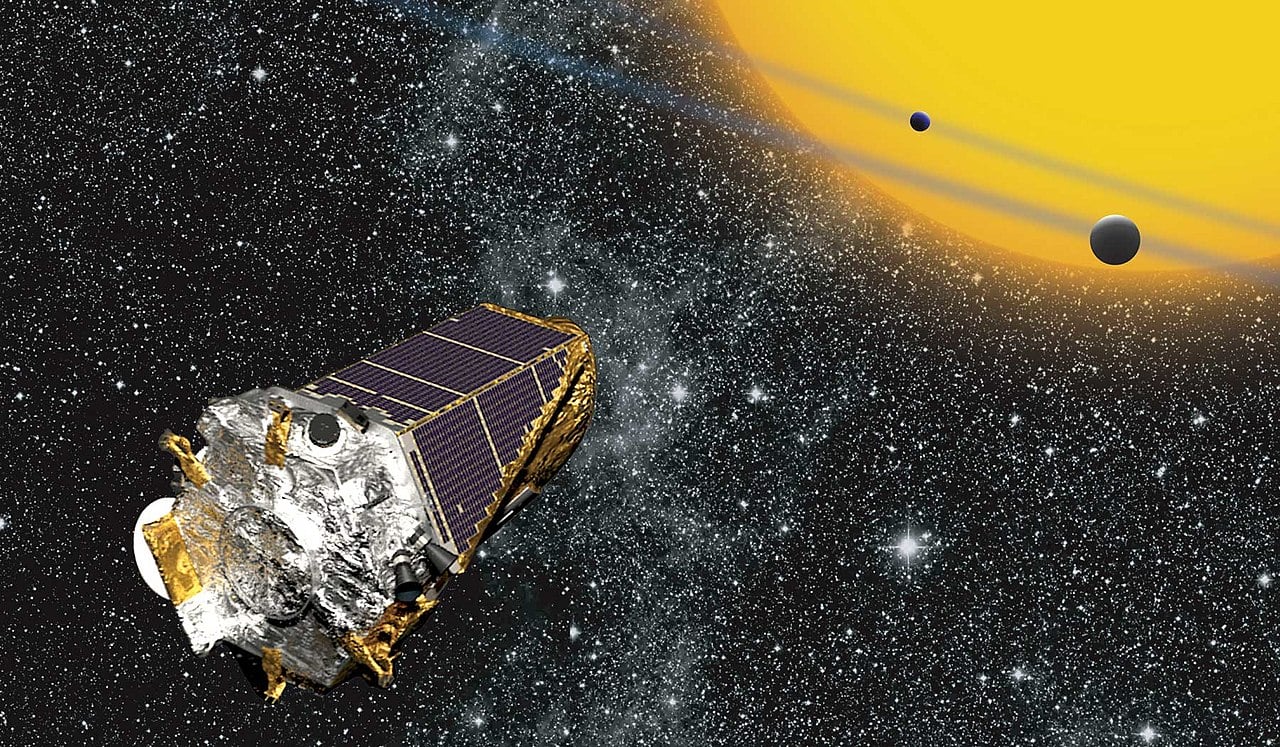

The researchers analyzed some of the data from the Kepler space telescope using a more sensitive method which has been developed over the years. The method could find an additional 100 exoplanets using the entire dataset from the Kepler mission. The findings about the new exoplanets were published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Unlike many of the 4,000 exoplanets discovered so far, which are grouped with Jupiter, Neptune and other similar-sized planets, the 18 new exoplanets are roughly Earth-sized. The smallest of the new planets is 69% the size of our Earth, while the largest is barely twice the size of Earth’s radius.

In their search for the 18 new Earth-sized exoplanets, researchers previously used the transit method, in which they observed stars and monitored their recurring drops in brightness caused by passing planets blocking their light.

“Standard search algorithms attempt to identify sudden drops in brightness,” first author Dr. Rene Heller from MPS said in a statement. “In reality, however, a stellar disk appears slightly darker at the edge than in the center. When a planet moves in front of a star, it therefore initially blocks less starlight than at the mid-time of the transit. The maximum dimming of the star occurs in the center of the transit just before the star becomes gradually brighter again.”

The transit method reveals that larger planets produce deep, clear brightness variations in the host star they are passing by. However, smaller bodies don’t block as much brightness due to their smaller size, making it extremely challenging for researchers to discover them. Scientists also have difficulties distinguishing between natural brightness fluctuations and variations that could be caused by a passing planet. However, the newer method could significantly improve upon the transit method and possibly reveal a lot more data from the Kepler telescope.

“Our new algorithm helps to draw a more realistic picture of the exoplanet population in space,” Michael Hippke of Sonneberg Observatory said. “This method constitutes a significant step forward, especially in the search for Earth-like planets.”