One of the best parts of having an investment process that appeals mostly to sophisticated investors is the introductory meetings are nearly always very enlightening for us. While we have long said we will never have a marketing person or department, a good many people do reach out and of course want to have a meeting as either a potential investor or just a like-minded friend. Earlier this year, when your author was asked by a potential investor about recent mistakes, an interesting discussion ensued.

At the time (August 2018), we hadn’t suffered any sizable losses due to research error. Yet, our mistakes were opportunities that failed to actualize the upside possibilities we had foreseen. We are intentionally not catalyst-driven investors and instead look for asymmetric risk-reward opportunities, whereby the quality of the team, company, industry and other factors will drive the realized performance towards the higher end of the range of possibilities. As we have discussed in the past, much like Quantum Mechanics has surpassed Newtonian cause & effect thinking, this process acknowledges that causality is nearly impossible to pinpoint with accuracy and instead looks for fertile preconditions with qualitative factors that will actualize this performance.

Q3 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

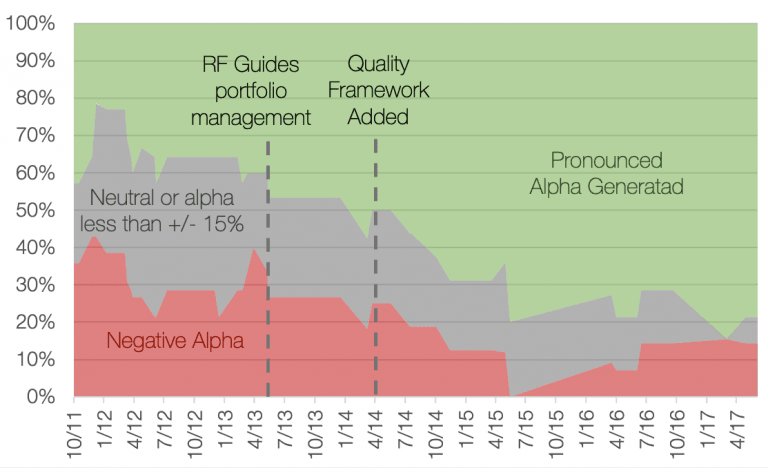

Since 2013, your author has used a force-rank methodology to help with workflow prioritization and portfolio management. Yet, in 2014, looking back on some of the mistakes he had made, he noticed nearly all of them correlated to a lower-quality management team and business model. Thus, our one-factor ranking framework of risk-reward had evolved to a two-continuum system that also sought to optimize for quality.

Exhibit 1: Investment Decision Outcomes by Date of Initial Decision – Trailing 15 Investments

After adding the quality continuum, many of our prior rookie mistakes were eliminated and the less favorable outcomes amounted to lost opportunities, or a high opportunity cost (“dead money”). In the August meeting, your author correlated this to the boiled frog syndrome that Charlie Munger has referenced in the past. The boiled frog syndrome references 19th century experiments that sought to show that a frog put into a boiling pot of water would jump out immediately, yet if the pot were heated only very gradually, it would not jump out and would get cooked to death. The premise was that the amphibian wouldn’t notice gradual changes in his environment. Later experiments have actually proved these experiments wrong, as frogs do indeed jump out of the pot when the water warms. Yet it would seem, frogs are better at adjusting to new information, as the incorrect analogy stuck with humans.

Humans are much less likely to respond to gradual changes in the environment. At the August meeting, your author noted that these “dead money” investments would likely materialize into losses in a market correction.

A few recent books have offered tools that we can use to solve this Boiled Frog syndrome from a portfolio management perspective. Brian Christian’s and Tom Griffiths’ Algorithms to Live By has a chapter entitled Explore / Exploit, which highlights how the principles behind the Gittins Index can help us know whether or not to search for an alternative or stay with the current choice. While the probabilities and the payoffs in the real world are far too complex to use an actual Gittins Index, the principle highlighted that the choice of whether or not to go find an alternative relates to how much time has elapsed. An example given was a gambler playing a slot machine whose luck had run dry. With each subsequent loss that the gambler incurred, he was more likely to find a better slot machine elsewhere. This runs contrary to many gamblers’ hope that the next pull will be different.

While some could extrapolate the Gittins index to mean that you should “let your winners run,” and “cut your losses,” the actual investment world is not that easy. In fact, some of our largest winners took a long time to payoff, and we had to endure ~30% drawdowns on some of our most profitable investments. The Fiat investment that we started in October 2011 went on to generate returns of nearly 10x including the value of our Ferrari stock, which we still own. Yet the Gittins Index does have a lesson to help prevent the Boiled Frog syndrome: the longer it takes for a company to actualize upside opportunities, the more likely we are going to find better investments elsewhere.

The chapter made many interesting points relating to explore versus exploit trade offs. Human biology gears us towards exploring everything in the beginning of our lives, such as your author’s nephew putting everything in his mouth as quickly as possible. Towards the middle of our lives, we tend to exploit the things that give us the best experiences, reliably. By the ends of our lives, we are eating the same foods, at the same restaurants, and with only a very few people. We are optimizing for different things depending on our lifecycle. We are biologically following the principle of the Gittins index.

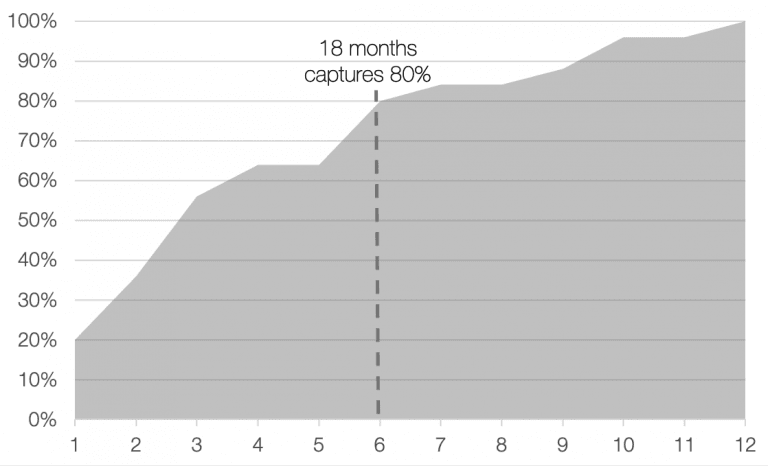

We sought to apply this lesson to an investment lifetime. Yet, for us to apply this Gittins lesson to our investment framework, we needed to know how long our typical successes took to perform above the benchmark index.

Exhibit 2: Number of Quarters it Took for a Successful Investment to Cumulatively Outperform the Index

We were surprised at what we found. Our successful investments have generated alpha far earlier than the Fiat example. Over 60% of these investments were generating alpha within the first year of our having invested, and by the time 18 months rolled around, 80% of them were generating alpha. Interestingly, the median drawdown that happened between the investment being initially purchased and it generating alpha was -15% with a maximum of -32% (MEI Pharma, another of our most pronounced winners). Of course, in nearly all of these opportunities, we took advantage of the weakness, and our cost basis was often lower than our initial purchase price.

As discussed in Philip Tetlock’s Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, the best forecasters are constantly updating their assumptions with relevant new information. In our ranking framework, we’ve been doing this since its inception back in 2013, and are constantly re-evaluating our portfolio against our pipeline of opportunities. Yet, as Tetlock showed, many of us tend to make only incremental updates to our forecasts, whereas the superforecasters were very good at making thesis-changing updates to their projections.

Under-reaction and over-reaction are the two biggest mistakes forecasters make. Because Mr. Market often behaves like a petulant child, he often gives an advantage to investors who are non-reactive and let reason prevail. Yet, in looking back at our most recent losing mistakes, the company fundamentals faced significant underlying changes in the operating environment, while we were only making incremental adjustments to our range of possibilities.

In order to prevent the Boiled Frog syndrome, we improved our process in a few new ways. First and foremost, we have decided that if a position is not generating alpha by the first year, we will throw out all of our old assumptions and re-underwrite the position with a completely refreshed set of assumptions. We will also demand a different analyst to come up with his or her own set of assumptions, and we will then compare our conclusions for a very honest conversation. As soon as Chris Torino joined the team, these frank conversations started on our legacy positions.

This doesn’t mean we will sell the investment, in fact, we specifically chose a year because only a year into our 14 mistakes (over the last decade), the average decline was only 21%. This is well within the typical draw-down experienced by our winners. This is key, because we do not want to fall victim to resulting, whereby we paint the fundamentals with our emotions. Had we realized that the circumstances had changed so dramatically in our two >15% losses in the past five years, we believe we would have mitigated the losses generated by these mistakes. Let’s give a recent example and do a post-mortem together.

The most pronounced mistake we’ve made since 2013 was that of Flybe. When we initiated the position, Brexit wasn’t even a word, the company had a very solid net cash position on the balance sheet, and the CEO’s plan at the time seemed very credible. Over our holding period, Brexit materialized and the company’s balance sheet flipped to a net debt position, leaving it more vulnerable to swings in the operating environment. This called for a superforecasting-style major update to assumptions, rather than the incremental adjustments that we made for passengers, yield and costs.

By the time we had implemented our re-underwriting process for our languid positions older than a year, and thrown out our old assumptions on Flybe, the stock had already declined precipitously. Yet, our re-underwriting process did save us from the pronounced >80% share price decline incurred subsequent to our exit.

Flybe prompted two additional criteria we’ve added to our ranking framework to evaluate the quality of a company. As mentioned before, we believe the qualitative aspects of a company will drive the results towards the top end of the range of possible outcomes. The two new criteria we’ve added are analyzability and an assessment of the board.

Analyzability was already implicit in our process of only investing after thorough research confirmed our assessment of the range of possibilities, quality criteria, and the expectations gap. Yet it’s also important to realize how knowable many of these assumptions are. One of our good friends at a well known investment manager has said it’s one of the most important criteria they use to rank their opportunity set.

For example, a new investment, Criteo, has customers that realize a 17x return on their marketing investment. That’s very analyzable and compares incredibly favorably to advertising alternatives. Conversely, we have no ability to know the correct range of possibilities in evaluating things like foreign exchange rates and commodity prices. In a messy Brexit scenario, we wouldn’t be surprised if the pound dropped to parity with the US Dollar. Sure, it’s an extreme and lower-probability scenario, but it’s no longer a >6 standard deviation possibility. Incorporating parity exchange rates into Flybe’s model puts the entire operation deeply in the red.

Similarly, the board at Flybe left a lot to be desired, and even left a lot of money on the table. Only six months before its shares collapsed, the board rejected a take-out bid at what would have most likely been 60x the price it accepted a couple quarters later (which we learned today was a ceremonial penny). The board had zero skin in the game, and behaved as such. Unfortunately, many corporate boards today are being run by golfing “yes” men and women who have no skin in the game and no right to be setting corporate policy. And many of them have no skill either. Yet, for management teams with no skin in the game, a common refrain to uncomfortable questions we ask are responded with, “that’s a board level decision.” This gives us little comfort when we hear these words.

We are excited to publish a white paper later this year which will highlight the pronounced outperformance of the “Builders,” who all have significant skin in the game. A board with skin in the game is an important aspect of nearly all firms that generate significant value for all its constituents, not just shareholders.

While we are determined to not let another Flybe happen again, we are also very thankful that our re-underwriting process saved us from significantly deeper losses which investors in the company are experiencing this very day. What board, in their right mind, would hire a bankruptcy attorney before trying to sell the company? Only one that has no skin in the game.

At one point, our Flybe investment generated returns of over 60%. One of the most interesting parts of studying our 14 loss-making mistakes over the past decade is that after investing in these mistakes, we had at some point made gains in all but one of them. The average gain in our “mistakes” was 38%, with some having doubled after we had purchased it. Having heard the Gospel of “buy and hold,” your author felt like a fish out of water trading in and out of our positions. Yet we aren’t fish, and just like frogs, need to realize there are some times we don’t want to be in the water.

These roundtrips became very rare after we implemented the quality criteria in our ranking framework. Under a two-pronged mechanism, as shares rise, the lower risk-reward in our ranking framework is very penalizing for lower quality companies. It is very uncomfortable having a full position in a company that is only ranking in the 50th percentile. This drove better selling behavior. Conversely, as higher quality companies’ shares rise, like Ferrari, the relative attractiveness doesn’t decline as precipitously. Although Ferrari trades at twice its public debut price today, we are net buyers of the name.

We have always gotten by with a little help from our friends. In 2014, your author’s (now great) friend, Dominique Levy at Sonian, highlighted that in selling positions she distinguished between whether or not the position was a compounder or a cigar butt. She had shared this wisdom with us just as our quality criteria was added to our process, and her suggestion has added significant value to our investors.

One of the most interesting aspects of the study we just conducted on our past successes and failures was that while our portfolio is higher quality today, the types of investments that we look at hasn’t actually changed much. What has changed was that we have been more active in managing the portfolio. In fact, 53% of our successes subsequent to our process change would have round-tripped or materialized in losses subsequent to our exits. Thus, the dramatic improvement in our hit rate displayed in exhibit 1 is due to better management of the portfolio. Many thanks to Dominique for her continued positive influence on our group.

For corporate strategy, Michael Mauboussin recently highlighted in his latest book The Success Equation this explore vs. exploit trade off. In rapidly changing environments, which we believe our economy has been in over the past decade, companies are better advised to invest in exploring new markets, new products, and new ideas. Yet, unfortunately most companies currently have exploitive strategies whereby they hamper innovation and growth, profit maximize and payout these short-term profits to shareholders. This exploit strategy only works well in a staid environment. Our white paper later this year will detail just how detrimental this exploitation is for these myopic boards and shareholders. Just like we prefer companies that innovate and explore, we prefer to explore ourselves, continuously feeding our pipeline of new ideas. Reducing opportunity costs in investing is nearly as important as avoiding mistakes.

At a recent event with author and professional poker player Annie Duke (hosted by a good friend), Annie told your author that she believed about 80% of the outcomes in poker were determined by luck. Continuous improvement of a player’s process can shift the contribution of skill from 20% to perhaps even 22%. This seemingly small improvement has very pronounced positive effects for those players over the long-term. Annie elaborated that making a 2% change in direction for the QE2 (Queen Elizabeth II, not Quantitative Easing II) when starting a voyage in New York results in a very different arrival point at the end of the journey. As Annie told us, simply having a process is a huge advantage in poker, where most other players have no process. Yet, like the QE2, with a short-term perspective, it is harder to identify errors in many processes. With a longer-term point of view, which we believe we now have with a decade of investments, we can extract some very useful lessons.

The biggest takeaway for us is that our process isn’t perfect and needs to continuously improve. The changes we implemented in 2014 and in 2017, with our expectations gap, have resulted in more reliable alpha. Our intentions have always been honorable and well-meaning. Yet as Jeff Bezos has said, “Good intentions don’t work, but mechanisms do.”

Just like Amazon has demonstrated, our process needs to be a constantly improving-mechanism. We believe by implementing our 12-month re-underwriting process, our board assessments and analyzability assessments, we are more likely to avoid becoming a boiled frog. We find it astounding that ~95% of our friends and peers in the investment management industry have no ranking process for their investments.

Our confidence is underlined by a key conclusion in Tetlock’s Superforecasting. Having a process by which a forecaster uses to drive the continuous improvement of one’s estimates is three times more likely than intelligence to predict the accuracy of the forecaster. With our new adjustments to our process and ranking mechanism, we endeavor to continue to reduce our mistakes and their effects on the portfolio. In a rapidly shifting world, we will now be far more sensitive to a warming pot. It couldn’t come at a more useful time, in this “age of accelerations,” where there will be many boiled frogs in markets.

Article by Steven Wood, GreenWood Investors