Pitch the Perfect Investment have just posted the first working paper by Paul D. Sonkin in their “Cognitive Finance Series,” titled, “Analogical Transfer As A Mechanism In Security Analysis.”

Abstract

The holy grail of manager selection is to identify those individuals who will outperform the market over the long term. Formal academic inquiry in the past has focused on the study of correlational attributes such as social networks,specialization and pedigree. In contrast, investigation into cognitive aspects of portfolio managers – how they perceive, assess, evaluate and process information to arrive at an investment decision – might allow us to isolate and identify causal factors in outperformance. The thesis discussed in this paper, that transfer and analogical reasoning in other domains can explain the mechanism by which portfolio managers analyze companies, is a first step in demystifying the analyst’s cognitive process. Different mechanisms of transfer have been documented by the empirical studies in different fields discussed in this paper. We have shown conceptually that the field of security analysis shares the same underlying structures as these other domains.

Q3 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Introduction

The ultimate goal, the multi-trillion-dollar question, that individual investors as well as allocators at pension funds, endowments and sovereign wealth funds are trying to figure out is which portfolio manager1 will outperform the market over the long term. In attempts to answer this question, previous academic research has primarily focused on factors that appear to correlate with performance including, but not limited to, psychopathy (Ten-Brinke, Kish, & Keltner, 2018), educational diversity (Tan & Sen, 2017), social networks (Cohen, Frazzini, & Malloy, 2010), personality (Noe & Vulkan, 2018), specialization (Kostovetsky & Ratushny, 2016) and skill (Ericsson & Andersson, 2005). While these factors document positive correlation, they have not established causality. What has been neglected in this body of research is an examination into the actual cognitive process of managers – how they perceive, assess, evaluate and process information to arrive at an investment decision.

One could argue that investor’s cognitive process has been addressed through extensive work in behavior finance, including the work of three Nobel lautarites - Richard Thaler, Daniel Kahneman and Robert Shiller. There are books written by them (Akerlof & Shiller, 2010; Kahneman & Egan, 2011; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008) and numerous others (Lifson & Geist, 1999; Mackay, 1869; Montier, 2009; Peterson, 2011; Peterson & Murtha, 2010; Zweig, 2007) on both individual and group investor psychology. But these works focus mainly on how heuristics and emotions like fear and greed can result in subpar investment results. They do not address explicitly how the manager perceives and evaluates information to arrive at an investment decision.

The belief is that if we can understand the cognitive process of managers, that we can isolate factors that differentiate the small minority of star managers that outperform from the vast majority that underperform. It should be noted that that minority is extremely small. According to the latest Standard & Poors SPIVA US Scorecard, over the past 15 years, 92.4% of large cap managers, 95.1% of mid cap managers and 97.7% of small cap managers failed to outperform the market (Soe & Liu, 2018).

Identifying causal factors for outperformance has wide implications not only in the selection of investment managers but also in hiring, training and teaching new entrants to the industry. The only work identified, despite extensive searching, that examines the investment process through a cognitive lens is my own. Sonkin & Johnson (2017) discuss how a portfolio manager builds-up schemas or checklists of investment likes and dislikes through many years of trial and error, which they use to, “…judge new investment candidates quickly. The criteria in the templates allow the manager to recognize patterns and act as a mental shortcut to reduce the time and energy needed to make and investment decision.” ( p. 342) While Sonkin & Johnson discuss the criteria managers use to evaluate new investment candidates, they fall short as they do not explain the actual mechanism of the analyst’s cognitive process works.

A money manager’s sole purpose is to earn an investment return greater than the market. If a manager cannot beat the market, an investor would be better off putting their money in low-cost index funds. The only way a manager can beat the market is by identifying a genuine mispricing (a mistake made by the market) by which they develop a variant perspective – a view that is different from consensus expectations. There are only three ways that this can be accomplished: through an information advantage (knowing something the market does not know), an analytical advantage (looking at the same data set available to all other investors but drawing a different conclusion that proves to be correct) or a cost or trading advantage (the ability to trade when others cannot or will not) (Sonkin & Johnson, 2017). The concept of transfer relates primarily to an analytical advantage. The successful manager has the ability to view a particular situation (the target), recognize that it matches a specific past situation (the source) or an amalgam of past situations (schematized source) and then map to the target to ensure they are correct. The faster or more accurately a manager can perform this process, the more successful they will be. Therefore, the concept of transfer is a critical element in understanding the cognitive process of successful portfolio managers.

Thesis

Transfer is evidenced in many domains that have similar problem-solving structures to security analysis including medical diagnosis (Lubarsky, Dory, Audétat, Custers, & Charlin, 2015), bridge (Charness, 1979) and chess (Chase & Simon, 1973). This paper explores how analogical transfer can explain the mechanism by which portfolio managers access existing knowledge and applying that knowledge to new situations they encounter. In this paper, the case for a conceptual model of transfer for security analysis will be laid-out and provide a basis for anticipated future empirical research.

Analogical Mapping and Transfer

Analogical reasoning is a core element of cognition. “Spearman (1923) once claimed that all intellectual acts involve analogical reasoning.” [emphasis original] (Novick, 1988, p. 510). Individuals make sense of the world by organizing objects into familiar categories. One way of forming categories is by analogy, which is the process of understanding a new situation by comparing it to a familiar situation. The familiar situation is called a base or source analog.

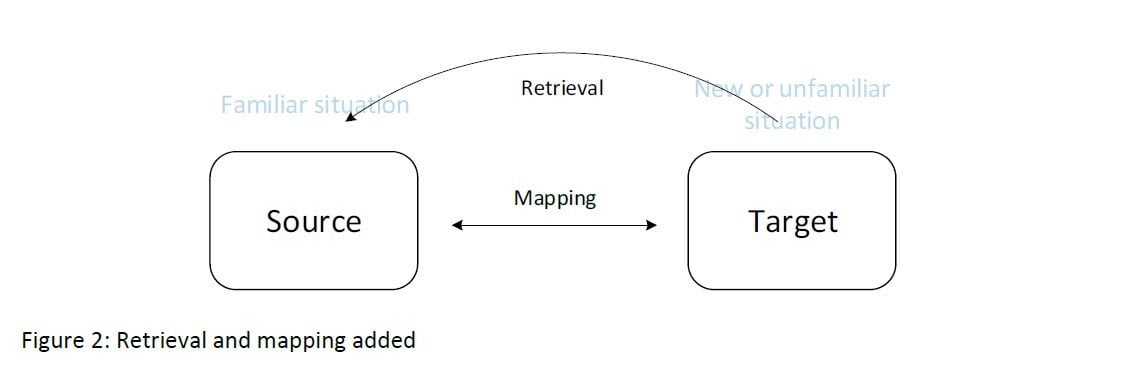

The new or unfamiliar situation is known as the target analog (Gentner & Holyoak, 1997) shown in Figure 1.

The study of how individuals reason by analogy through using previously acquired knowledge to bear on a new situation is known as “transfer.” Reasoning by analogy involves identifying similarities in the relational systems between two situations and making extrapolations based on these similarities (Gentner & Smith, 2012). In their 2012 paper, Gentner & Smith discuss a set of mechanisms that are present in all types of analogical reasoning. Retrieval is the ability to view a target and access a similar source present in the individual’s knowledge base. Mapping is the process of aligning the relational systems and projecting between the target and base. Evaluation is performed after the mapping is completed to judge the appropriateness of the pairing. Figure 2 adds mapping and retrieval to Figure 1.

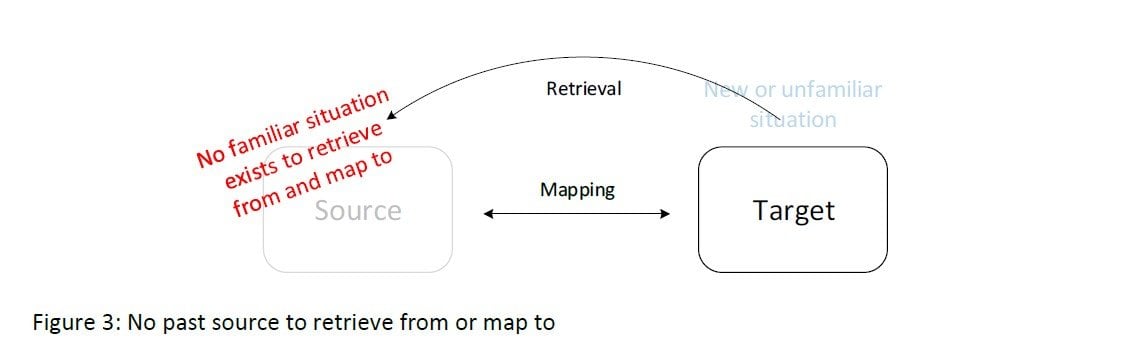

The ability to use previously acquired knowledge to bear on new situations can have impediments. If an individual has never encountered a similar situation, they have no knowledge base to retrieve from, or map to, as shown in Figure 3:

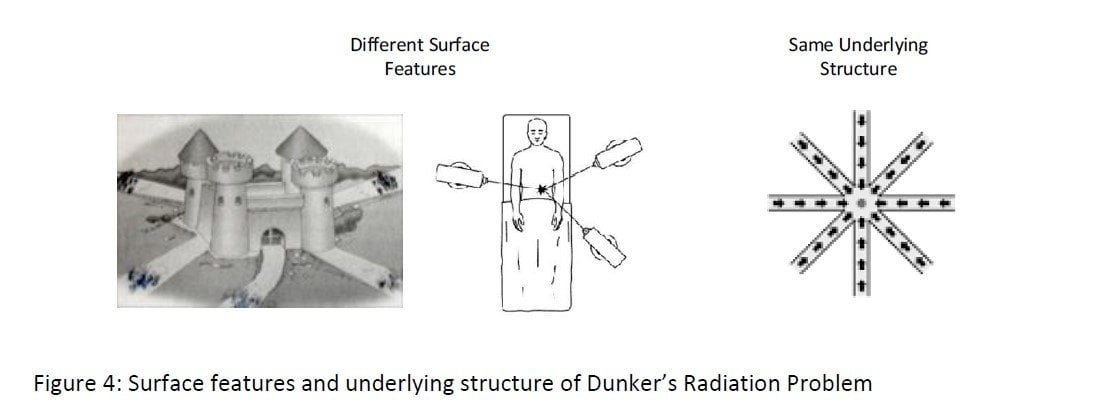

Even if the individual has the knowledge stored in their memory, they might not be able to retrieve that knowledge if they do not realize the relevance to previous situations. For retrieval to occur, the individual must not only have a similar source analog but also must notice the similarity of the source to the target. In a study involving the “Dunker’s Radiation Problem,” Gick & Holyoak (1980) asserted that if the source and target are drawn from different domains, the correspondences between situations will not be obvious. The study showed that transfer frequency was low when the surface features of the source and target problems were substantially different even though the underlying relationships were analogous. In this study, subjects first read a story about a military problem and its solution that was intended to serve as an analogous solution to a subsequent medical problem. The solution was identical for the military problem (a dispersion solution) but the surface features were different (soldiers attacking a castle vs. radiation attacking a tumor) see Figure 4. In one experiment, only 20% of the subjects produced the dispersion solution. This result highlights the fact that retrieval can be impeded when surface features are dissimilar even though underlying structures are the same.

To download the paper click this link.