China’s real growth rate has weakened, raising fears among investors that one of world’s largest economies may be on the cusp of a dramatic slowdown.

But, China is headed for something worse than a recession: a prolonged and fractious period with the United States, according to a new report by Bank of America, U.S. Trust.

It’s hardly a stretch to say that the U.S. and China have entered an economic cold war, a turn of events that have chilled the global capital markets and contributed, to the recent market swoon in equities, says Joe Quinlan, Head of CIO Market Strategy. The era of engagement is over. The two largest economies in the world are now rivals—a seismic shift the capital markets are only now beginning to discount.

Q3 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

China’s cyclical slowdown is less about trade frictions with the United States and more about policy-induced tightening measures. The latter includes the phasing out of preferential tax treatment for automobiles, undermining vehicle sales this year, and tighter credit conditions in China’s vast shadow banking system, subsuming fixed capital investment and related activities. The one-two punch slowed real growth to 6.5% in the third quarter—one of the weakest rates since the global financial crisis—and has raised fears among investors that one of world’s largest economies may be on the cusp of a dramatic slowdown in growth.

China, in our opinion, is not headed for recession but something perhaps worse: a prolonged and fractious period with the one country in the world that not only has the economic and military firepower to block or forestall the rise of the Middle Kingdom but also is determined, at least on the surface, to do just that: the United States.

Any doubts that the U.S. views China as a strategic rival, and is not in the “business as usual” mode, appears blown away by a recent speech by Vice President Mike Pence. The October 4 address was critiqued as “broader and deeper in its criticism of China than any other U.S. government statement of the past several decades.”1 A sampling: speaking to China’s military and economic objectives, the vice president proclaimed that the United States “will not be intimidated and will not stand down.”2 Another shot across the bow: “previous administrations all but ignored China’s actions. And in some cases, they abetted them. But those days are over.”3

Combative words, for sure—but not against a foe itching to go to war with the U.S. go to war with the U.S. but against a country which happens to be America’s top creditor (China owns nearly $1.2 trillion in U.S. Treasuries), key export market for U.S. companies (China accounted for 8.4% of U.S. goods exports last year, double the levels of Germany and France) and most profitable market for corporate America (last year, U.S. foreign affiliates earned $13.4 billion in China, more than in Germany and France combined).

The seemingly harsh words from the vice president preceded relatively harsh actions. Unnerving the markets, the administration has slapped tariffs on nearly half of all Chinese imports to the United States this year, and is threatening even broader restrictions. Against this backdrop, escalating U.S.-China trade tensions remains a dark cloud over the global capital markets, with little signs of dissipating anytime soon.

Across the Pacific, meanwhile, Vice President Pence’s adversarial speech left the Chinese people “upset and angry,” and was viewed as “unacceptable” by the government.4 The upshot: a full-scale boycott of American goods has yet to materialize but remains a risk the longer trade tensions simmer. Many Chinese producers have seen their costs rise and orders decline due to the U.S. tariffs, while the national government has been caught flat-footed by Washington’s tougher-than-expected hard line on trade with China.

The Clash of the Economic Titans

It’s hardly a stretch to say that the U.S. and China have entered an economic cold war, a turn of events that have chilled the global capital markets and contributed, in our opinion, to the October market swoon in U.S. and global equities. To wit, since the vice president’s adversarial speech on October 4, global equities have shed some $3.8 trillion in value, with the S&P 500 losing some $2.1 trillion. Other major indexes have also been hammered (Exhibit 1, which depicts the carnage of October).

True, the current market carnage reflects more than just rising U.S.-Sino tensions. A hawkish Fed, a backup in yields, fears surrounding peak earnings, Italian credit problems, U.S.-Saudi tensions—all of these variables have knocked the global markets for a loop this month.

But these factors are more cyclical than structural, and therefore are not as threatening to the capital markets over the medium term as is the fundamental rupturing/reordering of U.S.-Sino relations. China would rather deal with a cyclical slowdown, or even a recession, than have to adjust/revamp its economy in lieu of a tectonic shift in the U.S.-led global economic order of the past 70 years.

Remember, modern-day China grew up and prospered in the western liberal order the administration appears to be bent on dismantling. Prior to the administration, America’s approach to China was grounded in the belief that as China prospered and flourished, as millions more people achieved middle-class status, China would become more like the U.S.—or more liberal and pluralistic. Through greater economic convergence with the West, China would become a “responsible stakeholder” and embrace market and Western economic principles.

The gamble, however, appears to have failed. China, to a large degree, has played by its own rules. Noncompliance with many provisions of the World Trade Organization, championing large state-owned enterprises, intellectual property right violations, unfairly titling the domestic playing field against foreign companies—all of these characteristics suggest that China was never really serious about becoming the partner the West desired.

While the last quarter century in the U.S. has been about engaging China, that era is over. The two largest economies in the world are now rivals—a seismic shift the capital markets are only now beginning to price into assets. Recall that at the beginning of the year, the consensus was that Washington would push China hard on trade, accept some limited and symbolic wins, declare victory and move on. That scenario looks like a pipedream now—the U.S. and China seem destined for a long cold war.

Aftershocks

The adversarial stance of the U.S. toward China is just what Beijing can ill afford at the moment, in our opinion. Real growth is slowing. Inflation is on the rise. Private- and public-sector debt levels remain elevated. The brutal swoon in Chinese equities has undermined consumer confidence and wealth. Business spending has been trimmed owing to rising costs related to higher prices and rising wages. Offshoring among domestic and foreign firms is on the rise. The nation remains stuck in “middle class” status, with diminished odds of moving up the development ladder given the mushrooming confrontation with the United States.

In addition, with growth slowing and the government in the “whatever it takes” mode to keep the expansion alive, the country’s goal of “high-quality” economic development has been pushed to the sidelines. Structural reforms (including financial sector liberalization, cracking down on the shadow banking industry, opening the capital account, internationalizing the currency) remain a priority but have been downgraded as Beijing adjusts to a global trade and financial environment far more inimical to the long-term interests and goals of the nation.

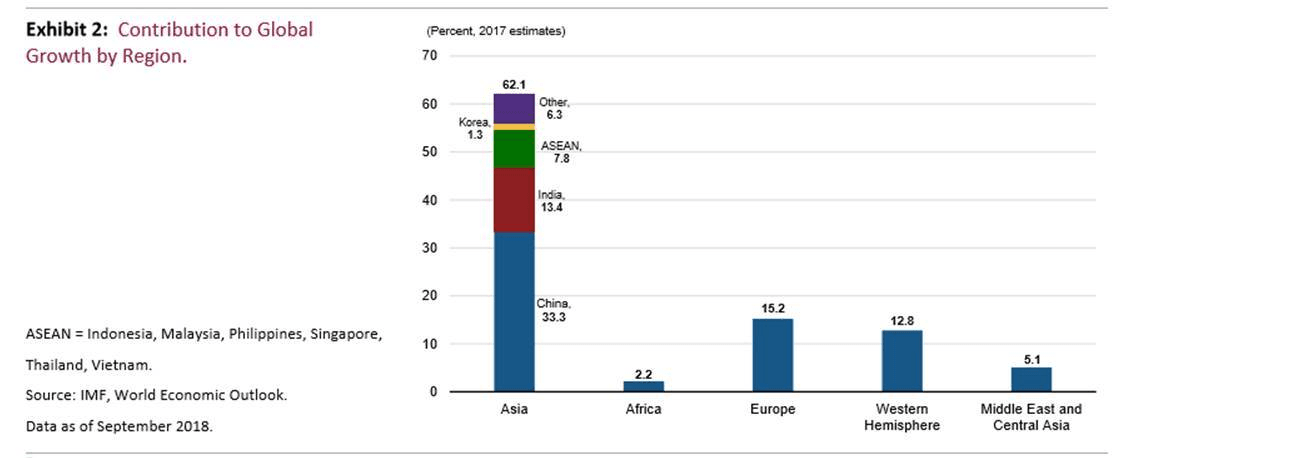

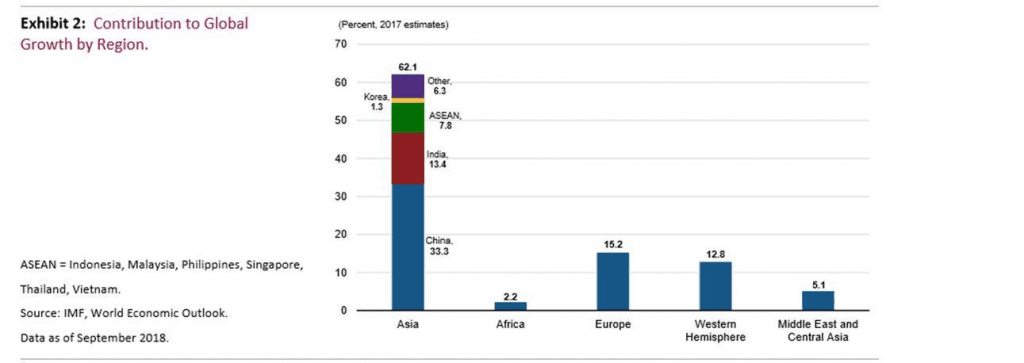

The upshot from all of the above: much-weaker-than-expected real growth from China over the near term, compounded by long-term challenges tied to a more combative United States bent on changing the structure of global trade and investment. This scenario is contributing to the current level of market volatility and intense downside pressure not only on Chinese equities but also on global equities. Remember: With China contributing to just over one-third of global growth last year, what happens in China doesn’t stay in China (Exhibit 2).

At risk to a prolonged U.S.-China trade war: real economic growth and earnings prospects in China, the United States and the world at large.

In the end, it’s finally dawning on investors that China confronts not only a much more fragile economic climate than previously thought, but also something perhaps even worse: the reconfiguring of the global economic order that has been so immensely beneficial to China’s development and emergence.

- See “The Crisis in U.S.-China Relations”, Richard Hass, The Wall Street Journal, October 20, 2018.

- See “Remarks by Vice President Pence on the Administration’s Policy Toward China,” The Hudson Group, October 4, 2018.

- Ibid.

- “The Crisis in U.S.-China Relations”, Richard Hass, The Wall Street Journal, October 20, 2018.