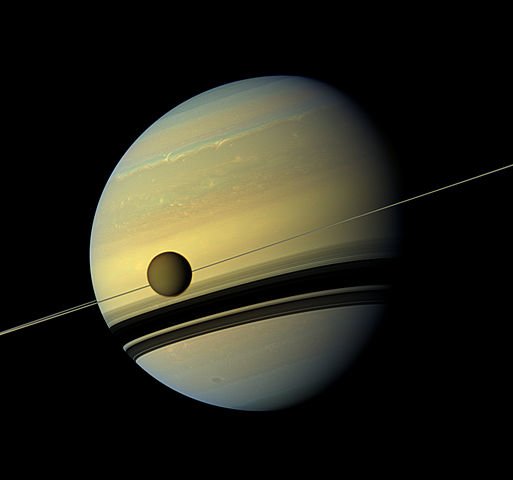

NASA’s Cassini mission ended in 2017 when the spacecraft that was exploring the gas giant Saturn plunged into its atmosphere, ending the mission. Still, scientists learned a lot about Saturn’s ring rain during Cassini’s final dive as it passed through the planet’s rings and upper atmosphere.

In a research study published in the journal Science, University of Colorado Boulder’s Hsiang-Wen (Sean) Hsu and his team revealed that Cassini managed to collect a microscopic material that falls from Saturn’s rings, also called “ring rain.”

“Our measurements show what exactly these materials are, how they are distributed and how much dust is coming into Saturn,” Hsu said in a statement.

The findings were made with Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer and Radio and Plasma Wave Science instruments and processed a little over a year after the spacecraft’s mission ended in Saturn‘s atmosphere. In the last days of the mission, which they’re referring to as the “grand finale,” Cassini completed a series of risky maneuvers which included zipping through the planet’s rings at 75,000 miles per hour to collect the final data.

“This is the first time that pieces from Saturn’s rings have been analyzed with a human-made instrument,” study co-author and CU associate professor Sascha Kempf said. “If you had asked us years ago if this was even possible, we would have told you ‘no way.’”

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) managed the mission, which was part of a cooperation between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Italian Space Agency. Ralf Srama of the University of Stuttgart led the study using the Cosmic Dust Analyzer, while William Kurth of the University of Iowa led the Radio and Plasma Wave Science.

In addition to learning about Saturn’s ring rain, scientists also got insight into the planetary dust, which is mostly made up of water ice, the main component of Saturn’s rings. Cassini also found a lot of silicates, which are small molecules that make up many space rocks.

“It is really difficult to maintain a pure ice surface in the solar system because you always have dirty material coming at you,” Hsu said. “One of the things we want to understand is how clean or dirty the rings are.”

Scientists had previously predicted Saturn’s ring rain when they studied the planet’s upper atmosphere. Studying the rings was not easy because whenever a spacecraft gets too close to a planet’s rings, there’s a risk it will be destroyed. However, with Cassini running low on fuel, the scientists decided to take a chance so they could record Saturn’s ring rain.

Cassini made 22 passes around the gas giant, flying through the planet’s closest ring and its upper atmosphere, which is less than 1,200 miles wide. Eight of the final orbits were used to trap charged bits of dust with the Cosmic Dust Analyzer. Based on the calculations the team made, that was more than enough ring rain to send roughly one metric ton of material into Saturn’s atmosphere.

“It’s a beautiful display of physics at work,” study co-author and CU Boulder physics professor Mihály Horányi said.