We are short shares of QuinStreet, a web-1.0 adtech firm that acts as a middleman between online advertisers and niche web sites. These niche sites attract visitors (leads) who are shopping for, say, a new credit card; QuinStreet acquires those visitors and delivers their data or eyeballs to advertisers, like credit-card companies, earning a fee along the way.

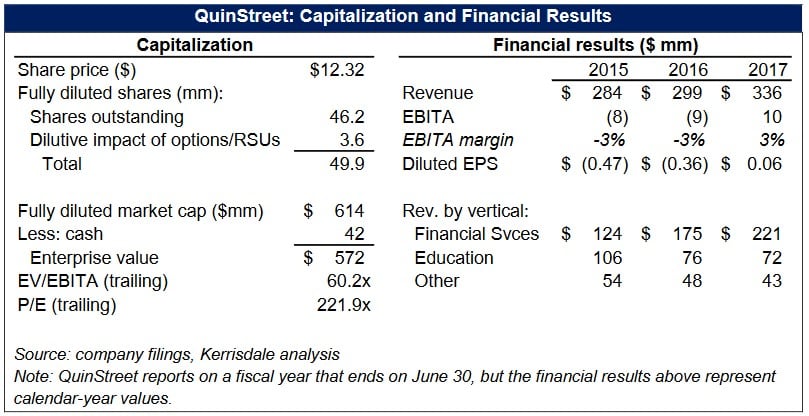

For much of QuinStreet’s eight-year history as a public company, its stock traded at less than half of its IPO price, as investors realized that QuinStreet’s outdated business model is unlikely to be a long-term survivor in the rapidly changing world of online advertising. But in the past eight months, QuinStreet’s share price has nearly quadrupled, fueled by a frothy market and a reversal of its longstanding trend of declining sales. QuinStreet now trades at a sky-high multiple of 60x operating profit.

In reality, few investors understand how QuinStreet actually does business, given the company’s bare-bones disclosures and scant research coverage. We believe the uptick in revenue is a sham: a mix of malware redirects, bogus leads from web surfers trying to score “swagbucks,” and a one-time lucky deal with Progressive that has already plateaued. QuinStreet isn’t a legitimate player in lead generation anymore; its proprietary web sites are nowhere to be found in top search results, and its click-monetization technology is routinely passed over in favor of its competitors’.

QuinStreet claims that it sources valuable “high-intent” leads for its advertiser clients. Then why is the largest source of traffic to QuinStreet’s main online hub over the past few months a fake site called Insurancebranch.com, which attracted users by simply paying them to click on its advertising links? Why is so much of QuinStreet’s other traffic coming from domain names associated with adware, paid surveys, and a mysterious individual in Hunan Province? How much of QuinStreet’s traffic – the very essence of its business – is genuine?

Drawing on extensive discussions with multiple former QuinStreet employees and other industry participants, we find that QuinStreet has little to differentiate it in a highly competitive market. Its technology is clunky, its sites commodity, its affiliate relationships fleeting. Unsavory business practices have subjected it to robocalling lawsuits and its inability to evolve at the pace of competitors has ruined internal morale. Unsurprisingly, key insiders, including QuinStreet’s CEO, CFO, and one of its earliest and largest institutional investors, have just recently begun to sell their shares. QuinStreet is not a road to riches; it’s a dead end.

I. Investment Highlights

QuinStreet’s recent revenue growth comes entirely from a single customer. Almost a quarter of QuinStreet’s total revenue is now attributable to the auto insurer Progressive – a fact that management and sell-side analysts have scarcely mentioned. In 2017, revenue from Progressive sharply increased, tied, we believe, to a new relationship in which QuinStreet supplies the competitors’ quotes that Progressive shows on its site to demonstrate its fairness and transparency. For the past three quarters, however, this Progressive revenue has flattened out, suggesting slower growth in the future. Strikingly, excluding Progressive, QuinStreet revenue has stagnated (and in fact declined from 2016 to 2017), casting doubt on the durability of its turnaround.

QuinStreet-affiliated sites benefit from highly suspicious web traffic. We used SimilarWeb, a standard tool for analyzing web traffic, to examine QuinStreet’s hub domain, Nextinsure.com, and discovered that the largest source of its recent traffic was a strange, now largely defunct, site called Insurance Branch. Piecing together several lines of evidence, we conclude that Insurance Branch is a QuinStreet affiliate that recruited users to click on its advertiser-sponsored links in exchange for an online currency called swagbucks. In this fashion, Insurance Branch effectively paid pennies for clicks worth dollars or tens of dollars to advertisers, using QuinStreet as a middleman and splitting the proceeds with it. But these swagbucks aficionados didn’t actually want insurance. They only clicked because they were paid to do so – exactly the kind of “leads” that no advertisers would knowingly buy. This phony, artificial click traffic casts serious doubt on the quality of QuinStreet’s product and thus its value to advertisers.

Nor was Insurance Branch the only anomaly we came across. QuinStreet affiliate sites also draw significant traffic from pop-up-proliferating adware; from a mysterious Chinese-owned domain called kptrk.us; from paid surveys; and from bogus message-board posts. It’s impossible for us to determine how widespread these practices are or how much QuinStreet is aware of them; one benefit of its reliance on third-party affiliates is plausible deniability in these situations. However, based on the available evidence, we believe suspicious and phony traffic play a significant role in its business.

QuinStreet’s business model is fundamentally flawed. QuinStreet is a middleman, intermediating between publishers and advertisers. But there are many other such intermediaries in all of QuinStreet’s verticals, and QuinStreet has few ways to outcompete them in the long run other than forking over more of its revenue to secure the loyalty of the few high-quality publishers available. As the advertising market becomes more sophisticated and efficient, QuinStreet will have fewer opportunities to profit, even as the low barriers to entry in lead aggregation subject it to constant competitive attack, often by new firms headed by former employees. QuinStreet is especially vulnerable because its verticals are among the most expensive when it comes to buying search-engine keywords, yet QuinStreet has never shown the willingness or ability to create genuinely compelling content that can attract visitors in its own right.

There Are Few Signs of a Sustainable Turnaround. QuinStreet features telltale marks of a business that’s gradually becoming obsolete. Despite its exclusive digital focus, QuinStreet relies on weak and outdated technology. Reviews from Glassdoor abound complaining about the legacy nature of the company’s systems and programs. The inefficiencies of QuinStreet’s technology is reflected in its lead gen sites; even after entering pages of personal information merely to be “matched” with a handful of supposedly relevant links, the user often has to enter the same information again after following those links to their destinations, and is sometimes forwarded to yet more lead gen sites. Then there is the matter of a litany of unwanted calls bombarding unsuspecting visitors – indeed, multiple consumers have recently sued QuinStreet, alleging that they in fact never did agree to be contacted via autodialer, making QuinStreet’s calls violations of the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA).

Comparable-company multiples suggest ~50% downside. Pulling together the available information on the valuations of three competitors and peers – MediaAlpha, Bankrate’s insurance unit, and Katch – we find that QuinStreet trades at a large premium to firms that not only have grown faster than it but even earn more absolute dollars of operating profit with fewer employees. Even giving QuinStreet the benefit of the doubt for its suspicious traffic, bad management, and weak long-term competitive advantage, its stock price should only be ~$5-7 – roughly 50% below the current levels. Interestingly, key QuinStreet insiders – its CEO, its CFO, and one of its largest early investors, Split Rock Partners – all launched stock-selling plans in the past few months, right as QuinStreet’s long languishing share price finally rebounded to $8, $10, and beyond – and after spending years patiently holding their shares at lower prices. We believe the message is clear: QuinStreet’s stock price has far outrun its weak fundamentals.

II. Company Overview

Founded in 1999, QuinStreet began life as a VC-backed effort to facilitate the online sales of “specialty goods.” For instance, QuinStreet created web sites to recruit affiliates for Rainbow Light Nutritional Systems (“a well-known premium manufacturer of multivitamins and food supplements”), Ariat equestrian footwear, and even Hooked on Phonics, promising that earning commissions on sales of these products offered “UNLIMITED income potential.” An early client was the for-profit online school University of Phoenix; QuinStreet created web pages to attract prospective students, collect their contact information and other data, and transmit it (for a fee) to the university. Soon it became clear that selling leads to for-profit colleges was more lucrative than selling leads to Hooked on Phonics, and for years QuinStreet focused on the education market, with little success in other areas.1

Beginning in its fiscal year 2007, however, QuinStreet – perhaps correctly suspecting that for-profit education was a shaky foundation for long-term prosperity – embarked upon an acquisition binge, spending almost $400 million over six years on more than 100 “online publishing businesses” designed to drum up customers for third-party advertisers in a variety of industries. The primary target was the insurance vertical, where QuinStreet spent $130 million on SureHits (an auto-insurance advertising platform analogous to Google AdSense), Insure.com, Insurance.com, and CarInsurance.com. But QuinStreet also expanded via acquisition into generating leads for home services (ReliableRemodeler), business-to-business sales (VendorSeek, Internet.com), mortgage lending (HSH.com), credit cards (CardRatings.com), and more.

Notwithstanding the costliness of these acquisitions, QuinStreet today derives only a small fraction of its revenue from web sites it actually owns.2 Instead, the bulk of the business comes from hundreds of third-party web-site operators – sometimes called “publishers” – who attract visitors by a variety of means and sell their clicks and contact information to QuinStreet, who re-sells them to insurance companies, banks, contractors, and other clients (sometimes including other lead generators and aggregators, who re-re-sell them). In the words of one former QuinStreet employee we spoke to, “QuinStreet makes it palatable for big brands to work with these kind of small, sketchy lead-gen partners.” While QuinStreet does sometimes partner with larger “publishers” – for instance, providing sponsored auto-insurance content to MSN Money3 – many of its affiliates are sites that few people have heard of, like bankdealguy.com, massagetherapyschoolsinformation.com, findyour-replacementwindows.com, and walkintubguide.org.

With its diversification initiative well under way, QuinStreet went public in 2010, pricing at $15 per share – below the original expected range of $17 to $19. Reportedly, the disappointing showing stemmed from “fears about potential obstacles to QuinStreet’s business of recruiting students for for-profit education companies,” especially in light of the regulatory “overhaul” that the Department of Education was then considering. These fears were soon validated. Revenue in QuinStreet’s Education vertical peaked in the first quarter of calendar-year 2011; since then, as stricter regulations set off the implosion of the for-profit-education sector – with an attendant collapse in marketing – revenue in the vertical has declined almost 70%.

QuinStreet’s other, newer verticals – Financial Services (primarily auto insurance) and Other (which includes home services and B2B) – were supposed to make up for potential weakness in Education. But they encountered their own problems. Beginning in 2011, increased competition in the online auto-insurance advertising market threw Financial Services into disarray, while housing-sector malaise and increased competition in B2B pushed “Other” off course. The graph below shows quarterly revenue in each vertical. It took more than six years for Financial Services to rebound back to its late-2010 peak; “Other,” meanwhile, is still in a drawdown.

Article by Kerrisdale Capital

See the full PDF below.