It’s human nature to want to protect your portfolio when the market takes a sharp turn. But too often, bond investors make the wrong choices when interest rates rise and credit cycles end. This can have disastrous consequences for returns.

[REITs]US Treasury yields have shot higher lately, albeit from very low levels, as the Federal Reserve raises interest rates and shrinks its balance sheet. Some investors worry that an already strong economy may be overheating, stoking fear that the Fed may raise rates more aggressively this year and rattling global bond and equity markets.

At the same time, the US corporate credit cycle is in its late stages, while the cycle for some European assets isn’t far behind. Corporate bond valuations are at multiyear highs on both sides of the Atlantic.

It’s difficult in these circumstances to know how to position and protect your investments. Rising rates make bond investors nervous and can lead them to make decisions that may haunt their portfolios for years to come.

There are two unforced errors that investors often make at times like this. Both can come at a high cost to long-term portfolio health and total return.

Mistake No. 1: Eliminating Exposure to Interest Rates

Many bond investors react to rising interest rates the way Pavlov’s dogs responded to lab assistants when they entered the room. The dogs associated an assistant’s appearance with dinner and salivated on cue. Many bond investors have become similarly conditioned by rising rates; their knee-jerk reaction is to reduce their portfolio’s duration, or interest-rate risk.

They do this by cutting back on high-quality government bonds, mortgage-backed securities and other investment-grade debt, or by focusing on shorter-maturity securities within these sectors. These types of bonds are highly sensitive to interest-rate and yield changes, so the shorter the duration, the less damage a rise in yields will do.

Shortening duration can make sense for some investors, depending on their strategy and risk tolerance. And it can help insulate a portfolio in the short run. But investors often overdo it. First, they reduce duration too drastically. Then, they take on too much credit risk, reasoning that high-yield bonds, emerging-market debt and other credit assets tend to do well when economic growth is accelerating.

In other words, they focus too much on the interest-rate cycle and not enough on the credit cycle. Why is this a problem? Because the two cycles are related. Growth-sensitive credit assets often do well in the early stages of a rising-rate environment. Eventually, though, higher rates lead to slower growth, the end of the credit cycle and, ultimately, an economic downturn. This typically hurts corporate profitability, increases defaults and decreases the value of many credit assets, including high-yield bonds and leveraged bank loans.

Treasuries and other government bonds, meanwhile, do well when growth slows. But investors who shorten duration too much when rates are rising won’t be able to pivot quickly enough to reap the rewards.

Of course, it’s impossible to predict exactly when a credit cycle—or the economic expansion that accompanies it—will fizzle out. But they all do eventually. And at 10 years and counting, the current US corporate credit cycle is one of the longest on record. Earnings growth is peaking at many companies, particularly those that borrow in the high-yield market, and stock buybacks are becoming more frequent—classic late-cycle behavior. That’s why understanding your portfolio’s exposure to the interest-rate and credit cycles should always be a priority.

Mistake No. 2: Believing Bank Loans Are a Cure-All for Rising Rates

Assuming too much credit risk when interest rates are rising is dangerous enough. But lately, investors have also been taking on the wrong kind of credit risk. Too many of them, in our view, have been rushing into leveraged bank loans without understanding the risks.

The logic is simple enough on the surface: bank loans have floating interest rates, so they should offer protection as rates rise. An added benefit: loans are more senior in a company’s capital structure than are bonds. If a borrower defaults, loan investors stand to recover more of their principal than do bond investors.

These two features make bank loans an easy sell in today’s environment. Unfortunately, neither is what it seems. Let’s start with floating rates. Loan coupons float and adjust based on movements in LIBOR rates. But they don’t budge until LIBOR exceeds a certain pre-set threshold. That means rates can rise for some time before the floating-rate benefit kicks in.

The problems don’t end there. Bank loans are callable—and they’re being called in massive numbers; 73% of outstanding bank loans were refinanced or repriced in 2017. Ironically, it’s rabid investor demand for these instruments that’s driving down yields and making it possible for borrowers to refinance at lower rates. Some 67% of outstanding loans were trading above par at the end of 2017, making them ripe for refinancing.

All of this has led to lower—not higher—coupons, even though the Fed has hiked interest rates five times over the past two years. For instance, as of February 28, the trailing one-year dividend income from one of the largest bank loan exchange-traded funds declined almost 22%, according to Bloomberg data.

How about returns? Loans delivered 4.25% last year, while US high-yield bonds returned 7.50%.

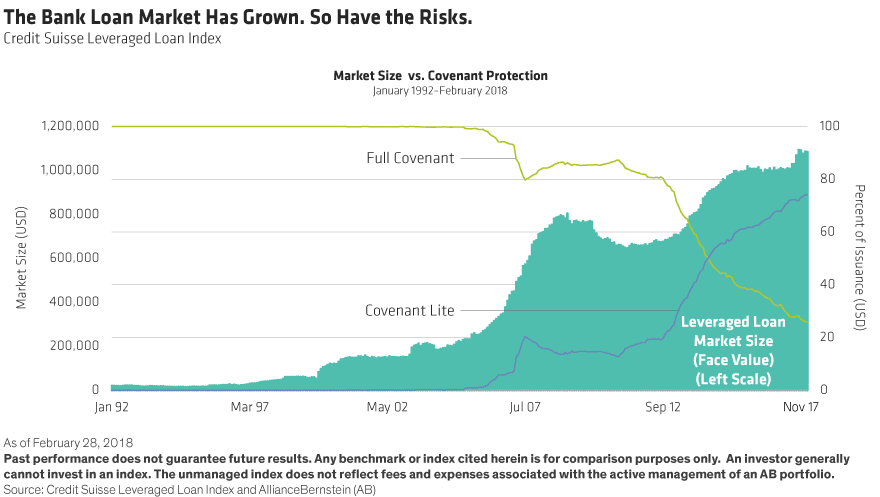

Seniority isn’t much of a selling point, either. More than half of loan issuers today have no unsecured bond debt cushioning their balance sheets. That’s important because the quality of the loans being issued has deteriorated. “Covenant-lite” deals that lack basic protections for lenders, including limits on how much debt a borrower can raise, have surged and now represent more than 70% of the market (Display).

To us, this suggests that default risk is a lot higher than many loan investors realize. And when those defaults happen, we think recovery rates are likely to be a lot lower than they’ve been in the past.

Learning from History

In our view, it’s best to blend interest-rate and credit risk, while avoiding overexposure to either one. Investors who do that—and who have an investment horizon of more than a few months—have nothing to fear from rising rates, since higher rates usually set the stage for higher returns (callable bank loans being the glaring exception).

Will some investors make these mistakes again when the current credit and economic cycles turn? We wouldn’t bet against it. But learning from the mistakes of the past can help us all avoid making them again in the future.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.

Article by Douglas J. Peebles, Alliance Bernstein