OK, that’s obviously not true. Let me downgrade it to “kind of neat.” Aaron and I build a simple, but powerful and intuitive, model for when a hockey coach should pull the goalie when trailing. Then, when the model reports that the coaches aren’t doing it nearly early enough, we ask why, and take away a perhaps surprisingly large number of lessons for portfolio and risk management, and business in general.

Here it is. Let us know what you think.

Article by AQR

Check out our H2 hedge fund letters here.

Pulling the Goalie: Hockey and Investment Implications

In 2016, Sports Illustrated named the 1980 “Miracle on Ice” as the greatest moment in sports history.4 A collection of US college hockey players from the University of Minnesota and Boston University, average age 21, beat the Soviet Union team on the way to winning an Olympic gold medal. The Soviets won every other Olympic gold hockey medal from 1964 to 1992 (outlasting the Soviet Union itself), and most international matches it played over 30 years.

Team USA went up 4-3 with ten minutes to play in the third period. The Russian team’s furious attacks were held off, and the Americans even got some solid shots on goal. But as the minutes ticked down, legendary Russian coach Victor Tikhonov did not pull his goalie to get a sixth attacker. Russian defenseman Sergei Starikov later explained that, “We never did six-on-five,” not even in practice, because, “Tikhonov just didn't believe in it.”5,6

Pulling the goalie is one of the more dramatic moves in hockey, traditionally credited to coach Art Ross7 in a 1931 playoff game between his Boston Bruins and the Montreal Canadiens. Down 0-1 with a minute to play, he sent goaltender Tiny Thompson to the bench and inserted a sixth attacker. It didn’t work, there was no more scoring and Boston lost. But a tradition was born. 8

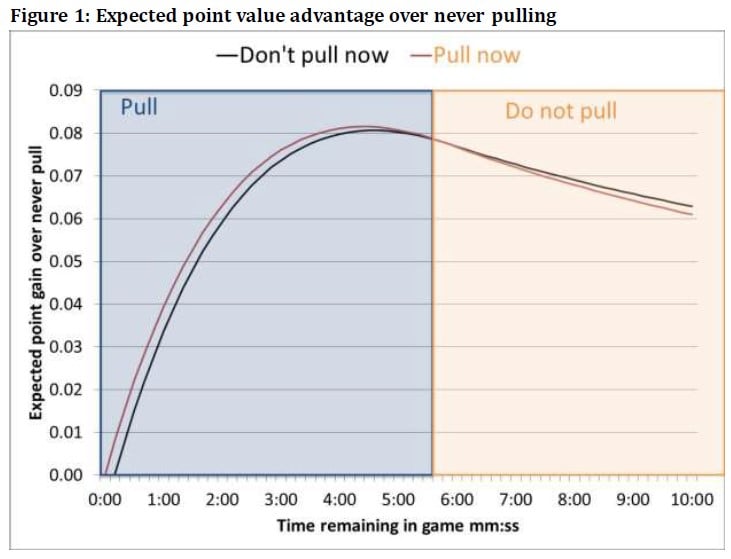

Actually, two traditions were born, one good, one not so much. Pulling the goalie is a sound strategic move, but waiting until there is one minute left to play is not. Only recently have hockey coaches begun to pull goalies earlier, and it’s still nowhere near early enough. 9

There have been a number of papers published on the subject using different models and data, but all agree that goalies should be pulled earlier than is the usual practice.10 Some, like ours, say it should be much earlier. Some of these models consider factors such as which team is better, who has the puck, what zone a faceoff is in, penalty situation, home or road game, among others. However, the focus of these papers is on hockey game advice. We do that too but that’s not our main goal. We consider the problem of optimal decision making in a broader strategic context, not to inform hockey coaches (though we’d echo the unanimous advice of this set of papers that they’re not pulling their goalies nearly enough, our model suggests pulling on the early side of all this research that recommends earlier action), but to illuminate how decisions are made and to recommend how to improve them. We apply these recommendations to our chosen fields of investing, business, and risk management.

We build a model that uses five inputs: the probability of scoring goals with a goalie in place, with the goalie pulled for an extra attacker, with a goalie in place but the other team has pulled their goalie for an extra attacker, the goal differential, and the time remaining in the game. This has fewer game-level parameters (3) and game situation parameters (2) than other models. 11 It’s not meant for precise calculation of real situations in individual games, but for assessing long-term average decision-making.12 Proceeding in this way creates a simple model with attractive intuition, which also yields many interesting comparative statics.13

For the probability of scoring goals while at full strength for both teams, we took the number of such goals scored in the 2015-16 NHL season (4,947) and divided by the total number of minutes played at that strength (126,425) to get an average rate of 0.0391 per team per minute (4.69 total even strength goals per game). We treated that as a constant for our analysis and broke it down into a 0.65% chance (.0391 divided by six) of scoring at even strength in each 10 second interval, ignoring the negligible possibility of multiple scores within the same 10 second interval. Using the same methodology for the 2,206 minutes played during the season with both teams at full strength when one has pulled the goalie, we get a rate of 1.18% per 10 second interval for the team with the sixth attacker14 and 2.58% for the team that retains its goalie.

Read the full article here by SSRN