“Don’t panic, buy the dip, who cares?” or “These are rumblings of an earthquake, people will be hurt like in 1929” – which one is it? I would call it a wake-up call. Let me explain:

In recent years, markets had appeared eerily “safe”. Central banks promised to do “whatever it takes”, provided “forward guidance” to keep rates low, even printed money to buy government debt, calling it “quantitative easing.” Sure enough, volatility has been low, valuations have risen. Now, just as the fellow from the cartoon above, many might have thought something isn’t quite right. As a result, many investors have been looking to buy some insurance, protection, just in case this goldilocks environment doesn’t last forever. For those who have looked for ways to protect against a decline, they likely noticed that it had been rather expensive. Indeed, we had come to the conclusion some time ago that it may be more prudent for many investors to hold more cash rather than hold risk assets on the one hand, but then, say, buy put options in addition. However, cash in a 0% interest rate environment is not sexy (and holding cash a recipe for professional investors to lose client assets), causing many investors to have come up with ever more creative ways to “diversify.” We put diversify in quotes because many investors may be fooling themselves: many of those alternatives are reaching for yield and may well be risk assets in disguise, meaning they may be similarly vulnerable in a risk off environment.

One way to buy “protection” is to buy derivatives or exchange traded products that rise when volatility rises. The most direct way is to buy futures on the volatility index VIX; retail investors bought an exchange traded note that invested in such contracts; note that the underlying derivatives periodically (monthly) expire, so there is a continuous rebalancing between the nearest contract and those further out. Anyone who has bet on a rise in volatility through these instruments knows that you continuously lose money, unless you get the timing right. That is, it costs you at times over 10% a month for the right to potentially benefit when volatility rises. I say “potentially” because it isn’t even assured you make money when you get the timing right because it isn’t enough for volatility to rise at any particular moment; to make money with these instruments, volatility needs to rise in the forward markets, i.e. the market has to price in higher volatility several weeks from now when the underlying derivative matures. Confused yet? I allege that many that have purchased these instruments do not fully understand them.

The hottest trade on Wall Street last year was to be “on the other side” of the fearful, that is to speculate volatility will remain low. Speculators could reap, and many did, over 10% a month, over 100% a year. What could possibly go wrong? Notably, the argument was that even if there was a surge in volatility, it would almost certainly be short-lived. So just as those buying protection were frustrated that the pricing of volatility in forward months didn’t move much, those selling volatility benefited from this stickiness. So what if you lose some money temporarily, you can surely take home riches over time?! Sure enough, ever more speculators followed the call of the sirens, piled into this must win trade. Except, of course, this wasn’t a must win trade. Instead, it was a disaster in the making. On February 5, in a 24-hour period, some exchange traded products lost over 90% in value. You make 100% in one year, then lose 90% in a day; for those that need a refresher how percentages work: if you start with $100, you temporarily have $200, but end up with $20, i.e. you lose 80%. Not. A. Good. Deal.

But what’s next? Have all the “short vol” speculators been flushed out? Is there any contagion, meaning are there any larger institutions that bet big on this, then have to liquidate other assets to meet margin calls? Are there related investment ideas that have similarly imploded or are about to? Should you buy the dip? Should you sell volatility now that the craziness is gone? Let me try to touch on some of these:

Risk Parity as a Source of Instability?

While the media has mostly focused on those crazy enough to trade volatility, the Wall Street Journal in a February 6, 2018, article, as well as a few others, have started to point the finger at so-called risk parity strategies as well. While risk parity strategies come in many incarnations, what they have in common is that they manage different buckets of generally uncorrelated assets, typically stocks and fixed income, so that each bucket contributes an equal amount of risk. Diversification is the one free lunch on Wall Street, so why not apply it in a risk parity setting. Indeed, if you google the topic, you’ll find an array of white papers. Some shops have gathered billions in assets promoting risk parity strategies. Indeed, the basic premise, I would agree, is sound and promising. However, just like any investment, there are risks associated with them, and too much of a good thing can be bad.

A common feature of many risk parity strategies is that they use substantial leverage in the fixed income allocation, as many types of fixed income investments are historically less volatile than equity investments.

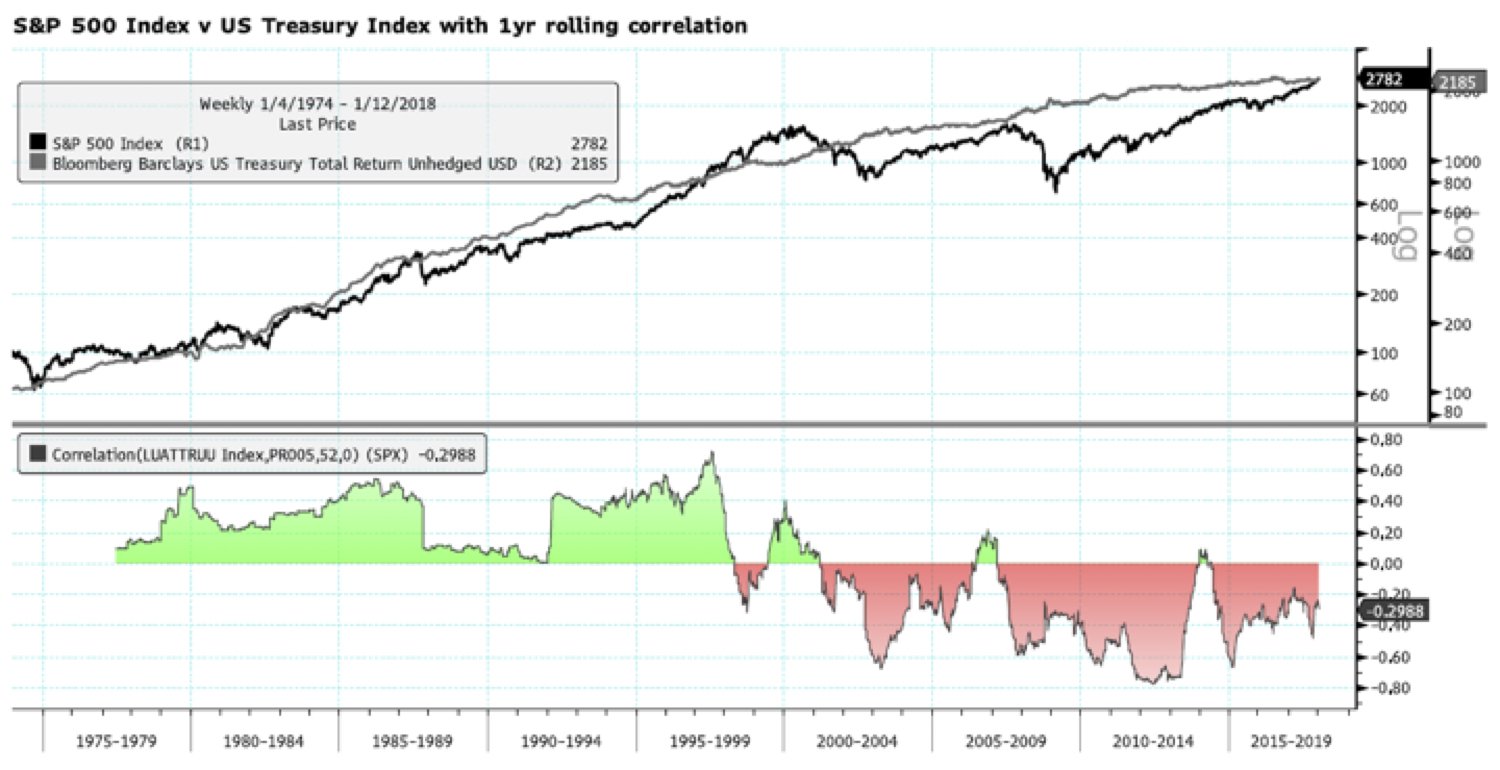

In the preceding, I emphasized “uncorrelated” and “leverage.” It’s kind of obvious that any strategy that employs leverage can create issues when it is very widely adopted. But what about the other basic premise of the risk parity approach? It’s based on the notion that stocks and bonds are either uncorrelated or inversely correlated with one another.(1) Intuitively, we all get that with regards to stocks versus bonds. Except it’s not always true. This notion of inverse relationship has been exacerbated due to the financial crisis because when there was a concern in the market (risk was off, equities plunged), the Fed would step in to buy the one thing it was allowed to buy (buy bonds, pushing bond prices higher). QE may well have exacerbated this perception, getting ever more investors to pile into this “proven” strategy. But have a look at the chart below that illustrates this relationship is far from stable; indeed, from the mid 1970s through the mid 1990s, there was a positive relationship between stocks and bonds (even if the correlation was often low):

Sure enough, on Friday, February 2, 2018, the business day before the 1000+ plunge in the Dow Jones index, both stocks and bonds plunged. According to our analysis, the week ending February 2, 2018 was the worst concerted selloff when stocks and Treasuries are considered together since 2009.

You may have heard business channels talking about “risk managers” are taking charge. That’s the professional’s version of selling when the market tumbles; when retail investors do it, they are ridiculed for letting emotions get in their way of investing, when professionals do it it’s prudent risk management. Go figure.

Relevant to the large selloff, however, is that risk parity strategies may well have contributed as portfolio managers scrambled to de-lever their portfolios.

Passive Investment Bubble?

In a February 6, 2018, CNBC interview, activist investor Carl Icahn took it a step further, arguing we are experiencing a passive investment bubble and that investors will be hurt like in 1929. He referred to recent events as rumblings ahead of an earthquake, calling the market a casino on steroids and that it had become a much more dangerous place. He added, however, that it is quite possible that we will be reaching new highs and that nobody could know when this would play out.

My take: I have referred to the recent surge in volatility as a wakeup call, urging investors to stress test their portfolios. I look at the markets in terms of risk scenarios. The scenario presented by Icahn, to me, is a very plausible one. Sufficiently plausible that I have, for years, been preparing myself to seek returns uncorrelated with risk assets. That’s easier said than done, as explained earlier: it’s not merely outright “insurance”, but many uncorrelated investments are expensive, that is, have “negative carry”, meaning it costs to hold them.

Is it Different This Time?

Sure enough, lots of pundits have come out encouraging investors to ‘buy the dip’. They point to the short selloffs after Brexit and the Trump election as to why this time should be no different. By all means, it is possible we will be reaching new highs before bigger problems unfold, but, absolutely, in my assessment, this time is different. What has been bizarre, irrational, unusual, you name it, is what I would call the period we had leading up recent events. By saying “this time is different”, I’m really only referring to those with a short attention span. In short, risk has come back, it’s come back with a vengeance, and, if I’m not mistaken, it is here to stay:

- The short volatility trade has been killed, it’s not coming back. Issuers of exchange traded products are retiring their products, speculators have lost their shirts. Importantly, at least for the time being, the “short vol” trade is, as of this writing, no longer a “positive carry” trade. That is, this fantasy world of reaping 10% a month has turned into a steep loss-making proposition because of how the market is pricing forward expectations of volatility. The relevance? In my assessment, the short vol trade itself has been a contributor to low volatility in the markets in a case where derivatives have driven the real market. That absurdity has stopped, allowing markets to be more volatile.

- Inflation expectations are rising. After all this technical talk, yes, the fundamentals are changing. The non-farm payroll report on February 2 suggested wage pressures are accelerating. This may well have been the trigger for bonds to sell off on Friday. Also keep in mind U.S. tax reform is generally considered stimulative; so is the more favorable regulatory environment; and, on top of it all, we might get increased infrastructure spending (it’s an election year, after all!). The relevance? Higher inflation down the road increases the odds of the Fed further stepping away from its accommodative policy. Just as the Fed has, in my assessment, been a major reason why volatility has been low, higher rates may well imply higher volatility on an ongoing basis.

- The Fed balance sheet is declining. The European Central Bank (ECB) is expected to taper its QE. Same as above, these are forces that, in my view, will cause volatility to move higher.

- The Fed was, in my assessment, unfazed by the selloff on February 5. So far, we have heard some regional Fed Presidents say just that, although adding that they will be gradual in removing accommodations. More relevant, though, is that our interpretation of market measures, notably those of future rate hikes and inflation expectations, were not shattered. This is consistent with our view of the Powell Fed, one that will be slow to react.

This doesn’t mean volatility will stay at the extreme levels we saw on February 5, but I consider it most unlikely that volatility will collapse yet again, with the VIX index staying below 10 for an extended period. I also believe this may cause havoc:

- I allege many investors did not rebalance their portfolios in the run-up we have had. To the extent that they did, they may not have moved stocks into assets that provide proper diversification. Most notably, many investors may have replaced their fixed income allocation with investments that only provide the illusion of diversification. That’s because the moment investors reach for yield, odds are their investments are more closely correlated with equities given that junk bonds, in my assessment, historically have a high correlation with equities. As a result, as volatility persists, investors may realize they are over-exposed to risk assets, causing them to sell.(2)

- Complacency continues to be very high. Anecdotal evidence I have taken suggests to me that most who are only casually watching the markets have not been impressed. Of course, this doesn’t assure turmoil must happen. But in my experience, a period of greed is followed by a period of fear. Maybe those are just silly words of someone who has been around the markets for decades. You judge.

- Institutional investors may be at a loss as correlations don’t work as expected. Portfolio managers at pension funds may be telling their boards about the pitfalls of risk parity investing, of their traditional asset allocation. But as any deviation from the index has caused investors to underperform in recent years, those board members don’t know any better. More broadly speaking, while passive investing has ruled the world of late, when volatility rises, the dispersion of risk may well go up, providing opportunities for active managers. I’m not sure whether Carl Icahn’s usage of the word “bubble” is the one I would use, but investors hugged to traditional “60/40” investing (60% indexed stocks, 40% indexed bonds) may no longer be the stars at cocktail parties and, to the extent they are board members of pension funds, they might want to brush up their resumes as their seats could be in jeopardy when their funds don’t meet targets. In the meantime, one of the largest fund management companies is telling advisors, they should really be only holding hands of investors and buying the index; I have a feeling, those advisors will need to do a lot of hand holding.

To dive into more depth, please register to join me at our Webinar on Thursday, February 15, at 4:15pm ET.

If you considered this analysis helpful, consider sharing this analysis with your friends. In the meantime, follow me on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook or Patreon.

Article by Axel Merk - President & CIO, Merk Investments

(1) Correlation is a measure of how two securities or asset classes move in relation to each other.

(2) Let’s keep in mind that when an investor sells a stock, someone else must buy it, stocks don’t disappear that easily. What does change is the value of stocks when there are many willing sellers and few willing buyers. The price has to come down to find willing buyers when supply (willing sellers) outstrips demand (willing buyers).