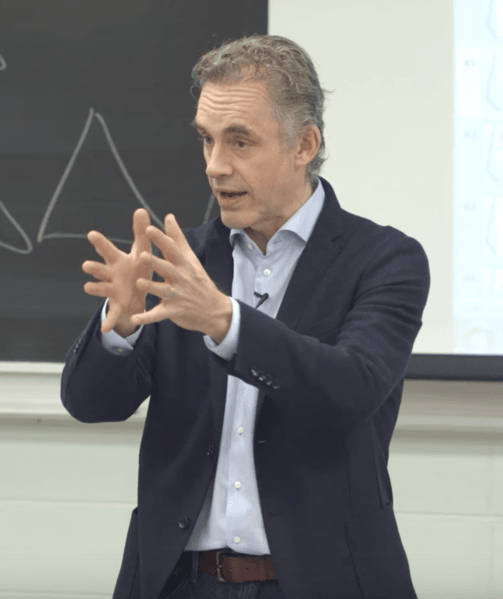

My social media feed these past few days has contained several references to the recent interview between Canadian psychologist Dr. Jordan Peterson and BBC journalist Cathy Newman. Throughout the interview, as Dr. Peterson gave his views on topics like feminism and LGBT rights, Ms. Newman routinely interrupted him with the meme-worthy phrase, “So what you’re saying is…” before re-stating what Dr. Peterson said in such a way as to make him appear prejudiced.

Dr. Peterson responded graciously throughout the interview, and the entire happening has been seized upon by multiple ideological viewpoints, from conservatives like Ben Shapiro who hail Peterson as a hero of free speech, to leftists who denounce Peterson as an alt-right troll.

Her ideology actually leads her to hear what she claims he is saying.

However, the seemingly simple ideological clash in this video reveals an unfortunately common truth – when discussing topics like prejudice, it seems that many of us aren’t speaking the same language. While we all are speaking English, the semantic meaning of the words seems to be completely different depending on which ideology you follow.

It is tempting for both sides to just dismiss the other as “wrong” or “stupid,” but what we have to understand is that, in conversations on topics like this, the ideological divide has become so deep that, in a sense, both sides are speaking a different language. Thus, when someone like Cathy Newman hears someone like Dr. Peterson speak, she’s not just trying to manipulate the conversation by putting words in his mouth; her ideology actually leads her to hear what she claims he is saying.

A New Definition of Racism

To understand how this fundamental difference in language originated, it is necessary to explore one of the most fundamental theories of modern prejudice: symbolic racism. Originally conceived as a psychological construct to help explain racism in post-Jim Crow America, it quickly became adopted not just in the psychological community, but in sociology, political science, and even economics, and currently defines much of our cultural discussion about prejudice of all sorts.

In 1973, in the aftermath of several race riots, America started to realize that, despite the successes of the Civil Rights Movement, we still had a long way to come as a society. Psychologists David Sears and John McConahay coined the term “symbolic racism” in their 1973 book The Politics of Violence: The New Urban Blacks and the Watts Riot, defining it according to three principles:

- A newer, subtler form of racism is emerging, due to societal pressure against explicitly engaging in the behaviors and attitudes of the Jim Crow-era

- This racism manifests itself in the sociopolitical sphere, with many using racially-targeted legislation to manifest their racism in a socially acceptable way

- This new, subtle, “symbolic” racism has its origins in being socialized to accept certain conservative values.

A Definitional Problem

The concept of symbolic racism is not without merit. Certainly, racism has not disappeared from America but has become more subtle, and certainly, there is such a thing as racially-motivated legislation masquerading as concern for “tradition.” However, the theory of symbolic racism goes beyond this by defining conservatism as inherently racist.

It no longer matters what one actually believes; the “true motive” can be determined by one’s political actions.

In their 1973 work The Politics of Violence, Sears and McConahay argue that to support equality for African-Americans, but not support government programs “designed to ensure” this equality is a form of racism. This element has defined much of the subsequent study of racism since then, seemingly to the regret of the original authors. In a 2005 paper written with Christopher Tarman, David Sears stresses that conservatism is a separate construct from political conservatism. However, whatever his original intentions, his theory has conflated the two.

Despite Sears’ buyers’ regret, the theory of symbolic racism inherently defines, through faulty logic, conservative/libertarian ideology to be racist. It does this in an especially insidious way; it necessitates that anyone who believes in equality of opportunity must support legislation such as affirmative action and welfare spending.

If a person does not support such policies, this can be interpreted as a sure manifestation of symbolic racism masquerading as political ideology. In this way, it no longer matters what one actually believes; the “true motive” can be determined by one’s political actions. Thus, fiscal conservatism has been inherently defined as a form of racism, by both social science and society at large.

Broader Influence

The equation of conservative ideology with racism is not supported by empirical research. In a 1998 paper, Bobocel and colleagues empirically demonstrate that there can be ideological opposition, entirely separate from racism or other forms of prejudice, to political policies supposedly designed to ensure “justice.” However, this empirical research has been ignored by scientists and society in favor of narrative convenience.

Almost every political move made these days is accused of being prejudiced; voter ID laws, welfare reform, Medicare reform, even tax cuts have all been furiously denounced as racist. Symbolic racism’s influence has also spread beyond the realm of racism itself, to almost every “ism” and “phobia” imaginable.

To believe in anything “traditional” is now a form of prejudice.

Every time someone disagreed with Secretary Clinton during her presidential campaign, that opposition was decried as sexism. Belief in the First Amendment is dismissed as “coded language” (a term derived from symbolic racism literature) for hate speech. Belief in the right to refuse service on moral grounds, such as wedding cakes or wedding banners, is equated to Jim Crow-era lynchings and violence.

Where the original theory of symbolic racism said that traditional values were only being used for racist purposes, the modern manifestation of this theory equates the two; to believe in anything “traditional” is now a form of prejudice. Combined with the popular predilection to refuse engagement with any sort of “prejudice,” and it’s no wonder that we’ve ended up in a society where no one seems to speak the same language.

“So What You’re Saying is…”

Faced with the realization of such a fundamental definitional difference, it is tempting to dismiss anyone who subscribes to symbolic racism theory as stupid, stubborn, or simply not worth engaging. However, it’s important to note that what we are dealing with here is a fundamental difference in worldview.

To engage with such people is less a matter of logical argument than it is apologetics.

In the nearly 50 years since it was first published, symbolic racism’s principles have gone on to define a majority of social scientific theories. It is as fundamental to the worldview of many leftists as free trade or free speech might be to those of us on the right, where it is often assumed to be true and not critically examined or questioned.

When confronted with a Cathy Newman-esque series of “so what you’re sayings,” it’s important to understand that this may actually be what they’re hearing. They are not necessarily trying to put words in our mouths or be disingenuous; they are trying to elucidate what they truly believe to be symbolic racism, hidden in our “coded” language.

To engage with such people is less a matter of logical argument than it is apologetics. We are dealing with a worldview so fundamentally different to our own, with definitions and presuppositions so different to ours, that we have to address basic assumptions, one of the most important of which is the theory of symbolic racism.

Aaron Pomerantz

Aaron Pomerantz is a social psychology graduate student at the University of Oklahoma. His interests, research and otherwise, include religion, sexuality, the effects of various media forms, and the influence of culture on human behavior.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.