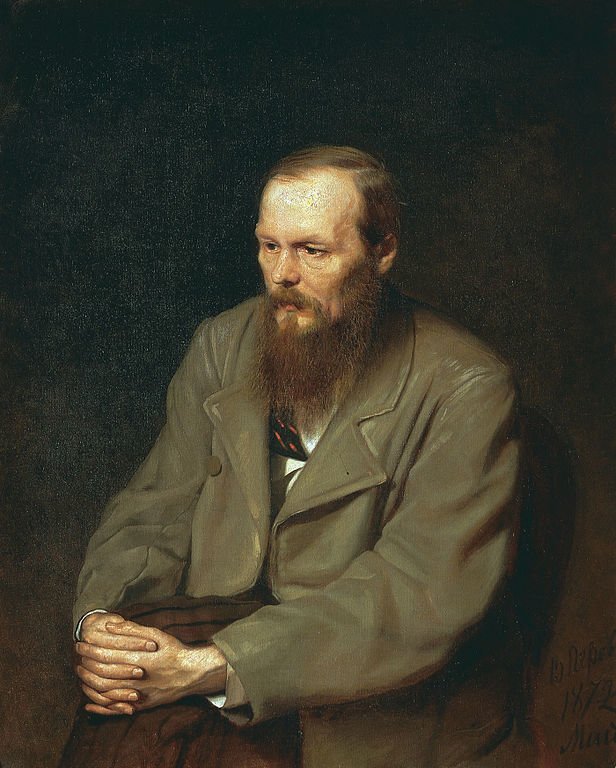

It was a cold December day in St. Petersburg when a blindfolded Fyodor Dostoevsky, who would later become one of Russia’s greatest writers, was about to be executed.

A Tactic of Terror

Due to his involvement in the intellectual group known as the Petrashevsky Circle, Dostoevsky, along with others, was sentenced to death by firing squad for propagating letters containing abusive remarks about the Orthodox Church and the Russian government.

The entire execution was just a performance, otherwise known as a mock execution, designed to instill terror.

The execution was to be carried out on the orders of Tsar Nicholas I, performed by a firing squad in a public square. “Performed” is an especially appropriate word as the entire execution was just that — a performance, otherwise known as a mock execution, designed to instill terror into the prisoners and dissidents.

At the very last minute, as the rifles were loaded and aimed, a messenger arrived on horseback waving a white flag and telling the armed men to stop the execution, on direct orders from the Tsar. This was not a show of mercy. It had all been planned. Every last detail — from the blindfolds to the firing squad, to the extraordinarily convenient last-minute messenger — had been pre-arranged in a twisted form of psychological torture.

Psychological Torture

There can be no doubt this incident had a profound effect upon the young Dostoevsky.

Those opposed to the death penalty are correct to point out the inherent injustice in the possibility of sentencing an innocent person to death and to cite the grossly expensive nature of capital punishment. At the same time, what should not be left aside in this conversation is the mental toll exacted on the individual who is sentenced to death by the state. My words would fall short of accurately describing this and I pray I never have the experience necessary to give an adequate account. Thankfully, for those of us lucky enough to be unacquainted with the death penalty, we need not rely on the words of any lesser a writer than Dostoevsky himself.

Two instances early on in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot seem especially autobiographical. The first is when the titular Prince Myshkin is discussing an execution by guillotine he witnessed prior to returning to Russia. His interlocutor makes the remark that at least there’s not too much suffering involved for the one sentenced to death by guillotine. Prince Myshkin thinks that may make the execution even worse.

“Take a soldier, put him right in front of a cannon during a battle, and shoot at him, and he’ll still keep hoping, but read the same soldier a sentence for certain, and he’ll lose his mind or start weeping.”

“Think: if there’s torture, for instance, then there’s suffering, wounds, bodily pain, and it means that all distracts you from inner torment.” As the character points out, “the strongest pain may not be in the wounds but in knowing for certain that in an hour, then in ten minutes, then in half a minute, then now, this second — your soul will fly out of your body and you’ll no longer be a man.” The chief characteristic, indeed the greatest suffering, lies in this absolute certainty.

Prince Myshkin contrasts this to other ways of being killed, saying, “a man killed by robbers, stabbed at night, in the forest or however, certainly hopes he’ll be saved till the very last minute.” He continues, “take a soldier, put him right in front of a cannon during a battle, and shoot at him, and he’ll still keep hoping, but read the same soldier a sentence for certain, and he’ll lose his mind or start weeping.”

In Those Final Moments

The other instance occurs when Prince Myshkin is retelling a story he heard from a friend who, much like Dostoevsky, had been sentenced to death but reprieved at the last moment.

Recounting when his acquaintance had “five minutes left to live,” he says, “it seemed to him that in those five minutes he would live so many lives.” He had divided those five minutes in a very particular way: the first two minutes were for saying goodbye to his fellow prisoners. Even the most casual of details are imbued with significance as seen in his recollection of “asking one of them a very irrelevant question and even being very interested in the answer.” The next two minutes were dedicated to thinking about himself. And the final minute was dedicated to looking around, where his attention was caught by rays of light on a cathedral’s dome and “it seemed to him that those rays were his new nature and in three minutes he would somehow merge with them.”

The only way to eliminate this suffering is to eliminate the death penalty.

Even the most ‘painless’ methods of carrying out capital punishment bring with them an immeasurable mental anguish. The evaporation of all hope, the certainty of death, and the state condemning a man to leave this world — in these there can only be inhumanity.

The only way to eliminate this suffering is to eliminate the death penalty.

The death penalty is one of the cruelest forms of punishment, not in the least due to the psychological toll it has on an individual. Others have not been as lucky as Dostoevsky, who faced ‘merely’ a mock execution and we would do well to remember their struggles and their pain today. I like to think that Prince Myshkin channels Dostoevsky himself when he remarks, “No, you can’t treat a man like that!”

Michael Hall

Michael Hall is the North Americans Communications Associate with Students For Liberty (SFL).

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.