After a record 2017, private equity funds have $1 trillion to deploy. The Financial Times reported this week that the buyout industry is raising more money than it can spend. As new risks surface, we think public equity portfolios with the right strategic mindset can deliver similar benefits to investors.

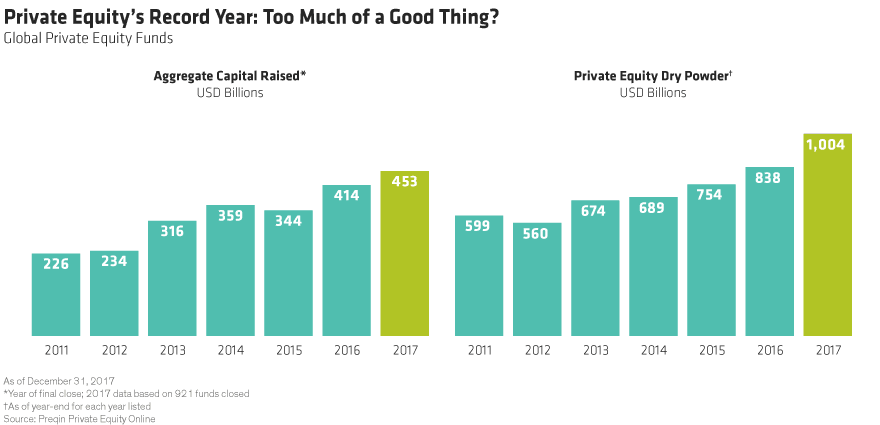

Fundraising is booming in private equity—but will this affect the industry’s return potential? In 2017, 921 funds globally received $453 billion in investor commitments, according to Preqin, an alternative-investments research group (Display). It’s easy to understand why. Private equity offers the prospect of higher returns than public equity portfolios. And returns from private equity are widely considered to be uncorrelated to stocks.

New Challenges for Private Equity

Turning new funds into investment returns could be more challenging in the coming years, in our view. Deploying private equity funds takes time, and with a trillion dollars now sitting on the sidelines, Preqin expects heightened competition for deals amid “very high” entry prices for assets. Leverage has reached alarming heights, with the FT reporting that the extent of debt used by US buyout firms to fund takeovers is “just shy’’ of the levels seen before the global financial crisis in 2007.

Investors also pay an opportunity cost for every month that their funds are not invested, especially as equity markets continue to rise. Meanwhile, the abundance of cash and a limited number of target companies could prompt private equity funds to buy publicly listed companies, which would benefit equity investors.

What about the benefits of uncorrelated returns? We think this perception is something of an illusion. Many people think private equity is uncorrelated with public equity, but nobody really knows, because private equity funds are not marked to market daily like stock funds.

In fact, we think private equity funds may be much more correlated to public equities than is widely believed. Private equity relies on cash flow and earnings growth for returns, which are directly tied to macroeconomic growth—just like stocks. So unlike bonds, which are uncorrelated to return sources derived from global growth, private equity can be expected to deliver performance patterns similar to equities, in our view.

Thinking Like Business Owners

We’re not saying that private equity isn’t effective. It is. In fact, what really defines private equity investors is how they invest. Private equity investors approach their targets like business owners. They study a company from all angles, searching for targets with true hidden value that can be unlocked through restructuring. Cash flows are the focus of company analysis based on internal rate of return (IRR) metrics that drive investment decisions. And by taking strategic stakes, private equity investors can effect real change in a company’s direction for the benefit of its clients.

Some of these methods are actually suited to public equity investing, too. Yet investors in stocks are often so fixated on beating an index that they rely heavily on market metrics, such as a stock’s beta or momentum, and may lose sight of the underlying business factors that drive returns.

Identifying Stocks Using IRRs

Thinking like a business owner is essential to being an effective investor in stocks, in our view. Searching for companies that will generate strong IRRs is a good way to generate consistent alpha that can help meet the same investment objectives associated with private equity.

Our IRR calculations use our analysts’ earnings forecasts to derive an annualized return rate from the cash flows that we expect the investment to throw off. These include both dividends and the expected proceeds if the company is sold back to the market after five years. Crucially, we assume (as private equity investors typically would) a conservative exit multiple that’s either equivalent to or lower than the current multiple. In other words, we look to IRRs to show the return potential from investing in a company based on our forecasts of its cash flows, without the benefit of any expansion of its stock market multiple or market re-rating of the stock.

Fees Matter

IRR-driven stock strategies can offer a handsome discount to premium private equity fees. Management fees for private equity funds are typically much higher than for stock portfolios, and that’s before the hefty performance fee is added. What’s more, private equity funds are illiquid and frequently lack transparency that is common for equity investment strategies.

Of course, not everything in the private equity arsenal will work for public equity investors. Leveraging businesses—a fundamental component of private equity investing—isn’t in the tool kit of a public equity investor. Public equity investors may not be able to make the same direct impact on a company’s strategic direction like private equity investors can. However, with a business-owner mindset, activist investors in public equities can influence management decisions on important issues.

We believe that by investing in stocks with a business-owner mindset, investors can tap sources of returns that private equity funds target but with several benefits. The money is deployed immediately and won’t be laying idle. Fees are typically lower. And in a concentrated high-conviction equity portfolio, investors can source stocks with relatively uncorrelated returns to the broader equity market. Private equity certainly has its merits, but with a trillion-dollar question hanging over the market, we think the IRR approach can be applied more efficiently to build a portfolio of global stocks that offer investors similarly rewarding returns—with much greater transparency.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. AllianceBernstein Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.

Article by Avi Lavi, Tawhid Ali Alliance Bernstein