Nothing is so contagious as example; and we never do any great good or evil which does not produce its like. — Francois de la Rochefoucauld (1613-1680).

Heroes for liberty are not peculiar to any region of the world or to a particular time period or to one sex. They hail from all nationalities, races, faiths, and creeds. They inspire others to a noble and universal cause — that all people should be free to live their lives in peace so long as they do no harm to the equal rights of others. They are passionate not solely for their own liberty, but for that of others as well.

In my last book, Real Heroes: Inspiring True Stories of Courage, Character and Conviction, I wrote about 40 individuals whose views, decisions, and actions served this cause in various ways. That book planted the seed for this new weekly series to be published each Thursday at FEE.org. But this time, others from around the world will do the writing, and I’ll be content to do the editing. It is my hope that when all is said and done some months from now, the literature of liberty will be greatly complemented by this collection of short biographies. The authors will be writing about heroes for liberty who are (or were) citizens of each author’s own country.

The subject of the eighth essay in this Heroes for Liberty from Around the Globe series is the Polish writer and anti-communist activist Ferdynand Ossendowski, a courageous man whose exploits deserve to be better known. Poland has produced an abundance of heroes in the last century, one of the reasons it’s been a very special place to me since my first of many visits there in 1986. The author is Mikołaj Pisarski, recently named the new president of the Mises Institute (Instytut Misesa) in Wroclaw, Poland.

--- Lawrence W. Reed, President, Foundation for Economic Education

It was early 1921 in Mongolia, an arena of conflict between Bolsheviks eager to coerce the local population into a new communist order and anti-communist “White Russian” forces. Inside an old Buddhist monastery on the river Orkhon, a secret meeting occurred between two important fugitives from tyranny. One was a 35-year-old named Roman von Ungern-Sternberg — an anti-Bolshevik general of German descent infamously known as “the Bloody Baron” for cruel treatment of both his enemies and his own men. The other was a 43-year-old Polish intellectual named Ferdynand Ossendowski, the man who would come to be known as “Lenin’s personal enemy.”

Ossendowski would give the communists fits for the next two decades.

Ungern had turned his attention to fighting Lenin’s Bolsheviks after his Asiatic Cavalry Division had just expelled the occupying Chinese from Mongolia. A mystic deeply fascinated by Tibetan Buddhism and consumed with a passion for restoring the Russian monarchy, he didn’t see eye-to-eye with his new Polish comrade on many issues. Ossendowski had no use for the monarchy. But the two were passionately united in their unremitting hostility for the Leninist regime in Moscow. From all indications, Ossendowski provided Ungern with valuable advice. In return, the Bloody Baron gave Ossendowski his means of escape: his private Fiat auto, an absolutely priceless possession in the middle of the vast Mongolian steppes.

By September, Ungern’s forces were crushed in East Siberia, and he himself was executed in Novonikolaevsk. Ossendowski made his way in the Fiat into China, then later to safety in Japan before arriving in New York City. It was there, in late 1921, that he published his first book in English, Beasts, Men and Gods. It described his travels during the Russian Civil War and the campaigns led by the Bloody Baron. It quickly became a bestseller. The following year, he settled in Warsaw, Poland. Thanks to the Bloody Baron’s gift, Ossendowski would give the communists fits for the next two decades.

Early Life

Now, let me turn the clock back a few years.

What really mattered for Ossendowski was the opportunity to explore more exotic countries.

Born in 1876 in Ludza (today’s Latvia), Ossendowski received a good education at a famous grammar school, where he exhibited traits of exceptional imagination. Tasked by one of his teachers to describe his family home, he instead provided a colorful account of one of Constantinople’s palaces. The headmaster soon declared that the boy was destined to become a great litterateur.

Before he could finish school, Ossendowski and his family moved to St. Petersburg, Russia. As an assistant to famous naturalist Szczepan Zalewski at Petersburg University, he had an opportunity to explore his interests in the natural sciences as well as his passion for travel. As a member of scientific expeditions, he visited many places secluded even by today’s standards: Altai Mountains, the Caucasus, the Janisej River, and the Baikal region.

During summer months, he often worked as a ship’s writer on the Odessa-Vladivostok line. The pay was not bad: 40 rubles per month. What really mattered for Ossendowski, though, was the opportunity to explore more exotic countries. He visited India, Japan, China, and the Malayan Archipelago. A few weeks that he spent in India resulted in his first significant novel, A Cloud over the Ganges, which received the coveted Petersburg Society of Literature Prize.

Ossendowski organized protests against the czar’s brutal repression in Russian-occupied Poland.

Getting Political

The young Pole’s academic career came to an abrupt halt in 1899 when, after taking part in student riots against the czarist government, Ossendowski was forced to flee Russia. He studied in Paris until he was able to return to Russia three years later and resume his promising career as a university professor.

Until the end of the First World War, Poland was not present on any map. Partitioned between Prussia, Austria-Hungary, and Imperial Russia in the 1790s, it had been wiped out for 123 years. The largest part of its territory was controlled by Russia, which undertook harsh measures of ethnic cleansing to “Russify” its Polish population.

After the failed Revolution of 1905 against the czar, in which he participated, Ossendowski played a significant role in upholding Polish traditions and language within the Polish community in St. Petersburg. He edited and produced several newspapers in collaboration with many individuals who would later help restore an independent Poland in 1918.

Ossendowski organized protests against the czar’s brutal repression in Russian-occupied Poland. For this activity, he was sentenced to death. He avoided execution (and was sent to prison instead) by convincing the judges and generals with the following explanation:

Had our committee been unable to take hold and contain the outbreak of revolutionary passions, you, dear Sirs, would undoubtedly have been slain by bullets of your own soldiers or hanged by anarchists raging like beasts

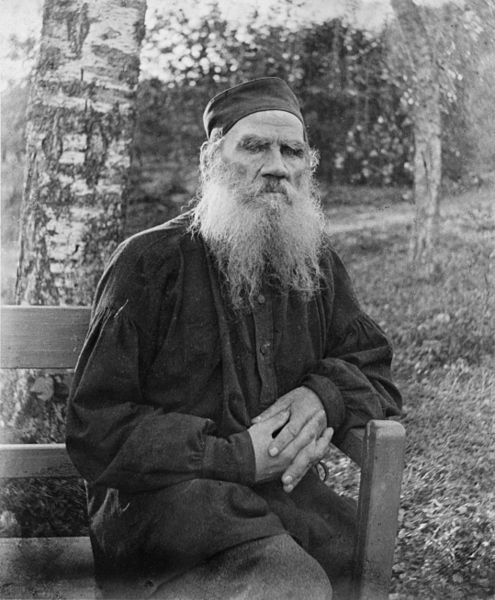

He left prison branded as a political prisoner, which prevented him from getting a job. Hounded by the czar’s secret police, he frequently changed his place of residence to stay a step ahead of them. During this time he wrote the first of his many anti-authoritarian books, “W ludskoj pyli” (In Human Dust), which described in detail the inhumane conditions inside the czar’s prisons. The book made him famous, earning praise even from Leo Tolstoy, who referred to it as one of his “favorites.”

A Man with a Mission

The 1917-1922 civil war between Lenin’s Bolsheviks and the anti-communist “White Russians” convinced Ossendowski of two things: to vigorously oppose Lenin and to make the country of his heritage, Poland, his new homeland. He believed that communism had to be stopped at all costs. It was that determination that took him to Mongolia and to the meeting with Ungern in 1921, after escaping the hellish nightmare of communism’s early days in St. Petersburg, followed by two long winter months of surviving in the Siberian wilderness.

A keen observer and a man of conscience, he was horrified by the unfolding terror of Lenin’s regime. He helped expose Lenin’s ties to German intelligence. He wrote much about the true nature of communism and the ugly truth about its leaders. He remained a dedicated enemy of communism for the rest of his life.

Ossendowski dared to challenge the myth, propagated by Lenin’s friends both at home and in the West, of the new Soviet leader as a heroic, positive figure instead of the power-hungry tyrant and remorseless war criminal that he was. His 1931 masterpiece, Lenin: God of the Godless, ripped that myth to shreds. His description of Moscow in the grip of Lenin’s dictatorship — “where justice was a mockery,” in his words — still elicits shudders in readers today:

There was no law but the anarchy of terrorism. All night long the machine-gun spluttered. Time after time the black van left the Bolshaya Lubyanka [a torture and execution center] to dump its load of corpses beyond the city. All day the limousines that once belonged to the court dashed through the streets carrying Commissars in leather coats, whose leather portfolios symbolized now the power of life and death. Then night came down again and the patrols, like wolves, broke into the rooms of private houses, ransacked them, and took away women and children to shame and death. Meanwhile, the church bells were silent and military bands played the Internationale on the Kuznetsky Bridge.

Lenin: God of the Godless was easily Ossendowski’s most important book. It provoked a strong response. Critics tried unsuccessfully to discredit his sources. Soviet embassies worked to get local governments to suppress it, but the message got out. Parts of it were reprinted in major newspapers, and famous actors read descriptions of Lenin’s brutality over the radio. Pope Pius XI sent his blessings and gratitude for his personal copy.

Late in Life

In the period between the two world wars, Ossendowski also earned a reputation as a globetrotter and an outstanding writer, often compared favorably to Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling, and Karl May. As a renowned Sovietologist, he published articles and secret reports on Revolutionary Russia.

He wrote several well-received novels and organized two expeditions to Africa. He was cited as one of the five most widely-read writers in the world. With dozens of published books, several of them worldwide bestsellers, it would have been easy for him to lead the life of a carefree socialite. But politics and world affairs ensured that he would become one of the most renowned and outspoken critics of communism.

The Soviets ordered the exhumation of his body to confirm that “the personal enemy of Lenin” was truly dead.

The German invasion of Poland started World War II in September 1939. Ossendowski remained in and near Warsaw during the Nazi occupation, assisting with the risky business of underground education in wartime. Even in failing health, he worked with the Polish underground to create post-war curriculum and education programs intended to rebuild the country’s devastated education system in a free, post-war Poland.

He died in January 1945 at the age of 68, just four months before the war ended. Two weeks later, when the Red Army seized the town of Milanówek where he was buried, the Soviets ordered the exhumation of his body to confirm that “the personal enemy of Lenin” was truly dead. The post-war, Soviet-imposed communist government of Poland banned his books and ordered existing copies confiscated and burned — proving that to a dictatorship, truth in the form of mere words is the greatest enemy.

More than seven decades later, we Poles understand and appreciate what Ossendowski did and what he stood for. In 1989, we demolished the communism that was imposed on us by Soviet power in 1945. We despise Lenin and revere our heroes of liberty. Ferdynand Ossendowski ranks as one of our best.

Mikołaj Pisarski

Mikołaj Pisarski is president of the Mises Institute (Instytut Misesa) in Wroclaw, Poland, an education-oriented think-tank focusing on advancing research on Austrian Economics and promoting its insights in Polish universities and high schools.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

![]()