Broyhill Asset Management investment thesis on Mexico’s airports.

The economic impacts of COVID-19 have been felt far and wide. The pandemic has indiscriminately affected both developing and emerging economies. The virus has shuttered some businesses but has also created some interesting opportunities for the long-term, value-oriented investor.

Emerging market air travel has been hard hit by the global pandemic. But air travel is key to economic development. Airports are recognized as critical infrastructure, supporting employment and fostering growth in tourism, trade, and business.

Broyhill Asset Management’s investment thesis below, highlights how private airports carry lower risk than airlines, generate higher returns on capital and benefit from a more stable, oligopolistic industry structure.

“Airlines are wonderful generators of profit—for everyone except themselves.” – The Economist

Summary

Despite what you may have heard, airlines have generated a steady stream of profits for decades. It’s just that those profits go to everyone else in the travel industry. While the current health crisis has resulted in an abrupt demand shock across the industry and again tested the economic viability of many airlines, other segments of the market are in a much better position to withstand this pressure.

Airports carry lower financial risk than airlines, generate higher returns on capital, and benefit from a more stable, oligopolistic industry structure. When an airline fails, its shareholders lose, but frequent flyers just migrate to the next best offer, so the overall demand for travel remains unchanged. The airport may see a temporary decline in revenue, but another airline will eventually fill the gap.

A perfect storm has hit airports located in emerging economies. Even before a global pandemic decimated travel, emerging market equities and currencies had drastically underperformed their developed market peers, particularly in Latin America. The world’s current challenges have only served to accelerate this trend. Smaller companies within these markets have underperformed even more. A reversion to the mean in any or all of these factors would drive substantial upside potential.

An investment in airports is not without risk. Airports still have to cover the high fixed costs of maintaining and operating infrastructure, despite the current collapse in traffic. But most airports have agreements with regulators that allow them to earn a fair return on their regulated assets. As a result, capital allocation and financial leverage are well managed and better suited for the periodic disruptions that have occasionally plagued the industry.

We expect the intrinsic value per share of our investments in the sector to grow at a double-digit annualized rate for the foreseeable future, driven by long-term passenger growth and pricing power. Should currently depressed valuations, oversold currencies, and the extreme underperformance of small-cap, value, or emerging market equities, revert toward normal, our upside would be significantly greater.

Industry Overview

Airports are essential to economic development. They have long been recognized as critical infrastructure, supporting employment, and fostering growth in tourism, trade, and business. More than half of Fortune 500 headquarters are located within ten miles of a hub, and nearly all are inside of 20 miles. In some cases, entire countries rely on airports as their primary source of income.

While most global airport groups are either fully or partially private today, this was not always the case. The privatization of the British Airports Authority in 1986 marked an important inflection point for the industry, demonstrating the value airports could generate when put into the right hands. Large infrastructure assets require multi-decade, long-term planning decisions to ensure sufficient capacity and growth. While lucrative if executed correctly, airports require significant capital investment, which is why many governments have sold to private buyers.

Over the past three decades, airports have evolved from government-owned, municipal infrastructure providers into sophisticated operators focused on cost-effectiveness, traffic efficiency, and return on capital. In public hands, many components of the business were undermanaged or ignored. But since the trend toward airport privatization has accelerated, sophisticated operators have increasingly invested in ancillary services to boost returns.

According to Airports Council International (ACI), the industry today generates $172B in annual revenue with an increasing number of airports having some form of private sector participation. Europe and the United Kingdom have led the trend toward privatization, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean. These more recently privatized airports are where we see the greatest opportunity for investment today.

Airport Economics

Most airports enjoy a dominant position in the markets that they operate in as a function of the following characteristics:

- Large initial investment. Finding a large tract of land and getting approval to construct an airport is not easy. As a result, most secondary airports are located in less convenient cities.

- Economies of scale. High fixed costs and large capital investments translate into declining cost curves for airport services. Economies of scale are driven primarily by passenger growth.

- Network effects. The network effects of a hub can serve as an effective barrier to entry, particularly if they have a lock-in effect on airlines and restrict contestability by new airports.

- Regulatory barriers to entry. Legal barriers to entry often take the form of monopoly rights granted to existing operators of local airports.

- Inelastic demand. Airport charges represent a small portion of total airline costs. Consequently, demand for airport services is relatively inelastic.

Mature airports enjoy a near-monopoly on a steadily growing passenger base, which generates both aerospace revenues (fees charged to airlines) and non-aerospace revenues (fees charged to passengers).

An airport’s ability to generate earnings is ultimately a function of passenger volumes and market characteristics. However, the earnings potential varies greatly depending on local regulations, which can govern the pricing of all or some airport services. Most regulatory systems fall under one of the following frameworks, with the primary difference being the treatment of non-aerospace revenues.

- Single-till regulation. Under a single-till framework, all costs and revenues are taken into account in determining allowed rates of return. The airport operates within the constraints of this overall price cap. Examples of single-till systems include the United Kingdom, Singapore’s Changi airport, and most airports in the United States.

- Dual-till regulation. Under a dual-till framework, regulations provide a set rate of return on aerospace revenues but place no limits on the income generated from the faster growing, higher margin non-aerospace revenues. Examples of dual-till systems include Australia, New Zealand, and Mexico.

Bottom Line: Airports are regulated, tollbooth-like monopolies with higher margins than most software companies.

Passenger Volumes

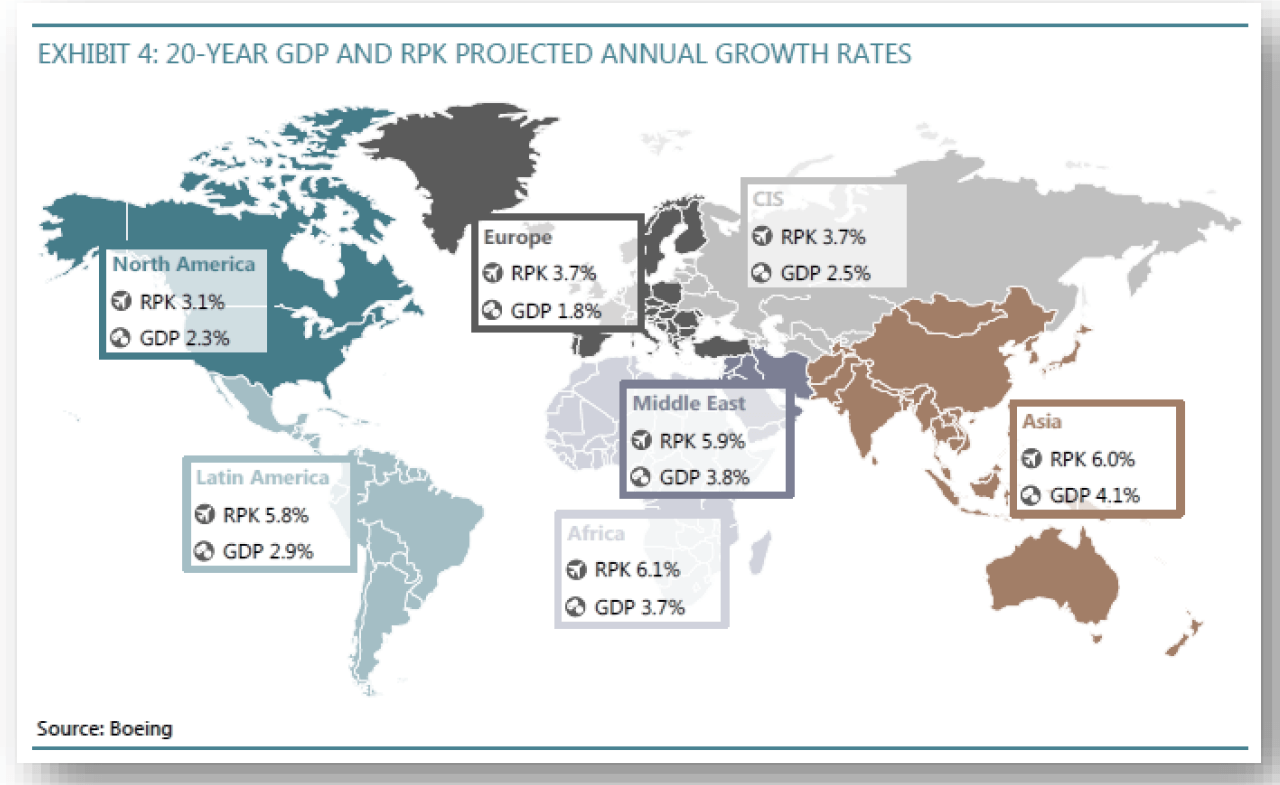

Passenger growth is the most important economic driver for airports. It drives aerospace revenues, retail revenues and car parking revenues. Airport traffic has historically grown at multiples of global GDP, or about 5% – 6% for the past decade, driven by increasing wealth per capita, declining costs, and general improvements in the experience.

Aerospace Revenues

Aerospace revenue is earned directly from the operation of aircraft, passengers, and freight. These fees are charged to the aircraft (i.e., runway usage, taxiways, boarding, parking, etc.) and the passenger (i.e., terminal charges and security charges usually included in ticket prices). Importantly, airport fees are a very small component of airline operating expenses and most of those fees are simply passed through to the passenger. ACI estimates that airports have held these charges stable at ~ 4% of airline operating costs for more than two decades.

Non-Aerospace Revenues

Non-Aerospace revenues are earned from various commercial activities in the terminal or on the surrounding land. They are equally reliant on traffic, generate the strongest growth, and very high returns on capital. Non-Aerospace revenues are an airport’s bread and butter because there is no limit on what a passenger can spend and no limit on the negotiations between the airport operator and retailer, etc. Airports can set their own prices on parking fees, concession fees, advertising fees, etc.

- Retail. Airports charge rent for space in the terminal for duty-free shops to restaurants and general merchandise. Leases are often structured with guaranteed minimums, inflation adjustments, and upside from sales growth. Retail revenues are ultimately driven by passenger traffic, with opportunities for incremental sales via mix, product offerings, and merchandising. Over the last decade, successful operators have increasingly manipulated the flow of traffic through the airport to maximize passenger exposure to this commercial space.

The “golden hour” for airports is that precious time between when a passenger passes through security and when they board their flight. People are in a different state of mind strolling through the concourse. If the merchandise is right and the supply is there, people won’t hesitate to open their wallets. As a result, airports can extract hefty rents for this limited space as retail tenants are happy to pay a premium for access to millions of wealthy passengers looking to spend their money before boarding their flight. Given the eroding value proposition of traditional malls and storefronts, we think the premium that brands are willing to pay to gain exposure to this captive audience will only increase with time. - Parking & Ground Transportation. Passenger volumes ultimately drive parking demand, along with related services for ground transportation, car rentals, etc.

- Hospitality & Real Estate. Large tracts of land surrounding airports can be developed into real estate for hotels, commercial use, and auxiliary activities outside of the terminal.

Expenses

The primary costs for airports are generally security, utilities, and facilities management. Costs are relatively fixed and usually scalable, meaning that as the number of passengers increases, costs per passenger decline, until the facilities reach capacity.

As a result, airports in smaller markets tend to have higher per-passenger costs relative to larger airports. The data show costs decline with size, which is a strong indicator of economies of scale. Most airports are small, and the industry generally follows the Pareto principle with 20% of global airports carrying the bulk of the passengers and cargo. While the industry, as a whole, is profitable, nearly two-thirds of airports operate at a loss, and 80% of airports with less than one million passengers lose money. Said differently, the returns generated on the world’s busiest airports are much greater than average.

Returns On Capital

As airports reach capacity, capital investments increase to fund expansion, increasing fix costs until utilization increases. Given the high fixed cost base for maintaining and operating commercial airports, it is important to understand that these investments are often made to generate additional aerospace revenues based on a cost-recovery or cost-plus model, ensuring an adequate return on capital.

Capital expenditures fund capacity expansion and facilitate long term passenger growth. Airports are typically able to increase charges following capacity additions to ensure a fair return on capital. While asset-intensive in nature, a large portion of capital expenditures is needed to accommodate rapidly growing passenger traffic. Consequently, maintenance capex is significantly lower than reported and depreciation is a better proxy for normalized investment and free cash flow.

Capacity growth allows for new passengers. New passengers generate incremental aerospace revenues as well as incremental passenger spending on non-aerospace revenues. So while the direct returns on capital investments are regulated, the growth in passengers driven by capital investments also fuel non-regulated revenues with no limitations on profitability, ultimately generating significantly higher returns for well-run airports.

Airports In Mexico

Aviation is a key component of economic growth, facilitating trade, travel, and tourism in Latin America. The growth of passenger air traffic in the region is among the highest in the world, driven by rising income levels, continued growth of the middle class, and economic cooperation from NAFTA and CAFTA. Passenger growth between Mexico and the US is among the largest contributors to traffic in the region.

Airports in Mexico were government-owned until 1998 when they were privatized in order to upgrade and expand the country’s infrastructure. The largest airports were divided into three publicly traded corporations – Grupo Aeroportuario del Sureste (ASR), Centro Norte (OMAB), and Pacifico (PAC) – with 50-year concessions that regulate each company’s operations. Cancun, Guadalajara, and Monterrey airports represent the largest geographic anchor for Sureste, Centro Norte, and Pacifico, respectively.

Under the current system, each airport submits a Master Development Plan (MDP) to Mexico’s “Ministry of Communications and Transport” who then sets allowable tariff rates for the next five years, based on expected traffic growth, planned investments, etc. Importantly, these rates are adjusted for inflation annually and have grown at mid single-digit rates in nominal terms over the last decade plus. The dual-till system in Mexico puts a cap on aerospace revenues, incentivizing management to maximize unregulated, non-aerospace revenues.

Passenger traffic has grown at over two times GDP growth over the past two decades driven by multiple factors. Air traffic penetration remains depressed even compared to other LatAm countries. Trips per capita in Mexico reached 0.4 in 2018 compared to 0.5 for Colombia, 0.7 for Chile, and 2.4 in the US. The emergence of low-cost carriers, which now claim greater than 50% market share, has also made travel more affordable. Yet, Mexico’s bus market remains massive, selling more than 3 billion tickets annually, relative to some 50 million domestic air passengers. Rising incomes and declining costs for air travel represent significant upside potential for airport share gains.

All of the publicly traded airports in Mexico are well capitalized with strong balance sheets, less than a turn of leverage, and ample liquidity. They are also no strangers to crisis. They have successfully navigated the Mexican Peso crisis, the 1997-1998 emerging market crisis, September 11 attacks in 2001, major hurricanes in 2005, the financial crisis in 2008, and the bankruptcy of over 50% of the airlines in Mexico. Following each of these events, traffic recovered, then continued to grow. Over the past decade, PAC, ASR, and OMAB have grown passengers at 9.5%, 8.2%, and 6.9% annually.

Grupo Aeroportuario del Sureste S.A.B. de C.V. (ASR) operates airports in Cancun, Cozumel, Merida, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Huatulco, Tapachula, Minatitlan, and Villahermosa. ASR’s MDP was negotiated in 2018, and while it is more heavily driven by traffic than peers, management has the option to renegotiate the entire agreement if Mexican GDP were to decrease by 5% or more.

Cancun is Mexico’s second-busiest airport, after Mexico City. The airport, which accounts for nearly half of ASR’s total traffic and three-quarters of traffic at its Mexican airports, is ASR’s crown jewel. Cancun is a world-class vacation destination with significant room capacity. If crowds on Long Beach Island, NJ and Myrtle Beach, SC are any indication of pent-up demand, US tourists (which represent over half of Cancun’s international traffic) should drive a sharp recovery in ASR traffic. It’s worth noting that any discounting by airlines and resorts to fill seats and rooms during a downturn, also accrues to airport operators who benefit from increased traffic without the need to reduce prices.

Today, traffic outside of Mexico (mainly in Columbia and Puerto Rico) represents 40% of ASUR’s business. Nearly half of ASUR’s revenues and the majority of its debt are denominated in USD. Net debt-to-LTM EBITDA stood at 1.1x at quarter-end, with interest coverage (per debt agreements) at 5.0x.

Grupo Aeroportuario Del Centro Norte

Grupo Aeroportuario del Centro Norte, S.A.B. de C.V. (OMAB) operates international airports in the northern and central regions of Mexico. The airports serve Monterrey, Acapulco, Mazatlan, Zihuatanejo and several other regional centers and border cities.

Monterrey is OMAB’s most important asset and accounts for nearly half of OMAB’s total traffic. While the airport is highly dependent upon domestic business travelers, it has started expanding routes to the US. With nearly 90% of its passenger traffic domestic, OMAB’s corporate traffic should hold up better than tourism in the short term. Longer-term, we think Monterrey, the commercial and industrial center of Mexico, is poised to be a significant beneficiary of near-shoring in a post-COVID world.

Management’s growing focus on non-aerospace revenue has driven increased profitability. Adjusted EBITDA per passenger has grown ~ twice as fast as revenue per passenger; revenues have grown approximately twice as fast as passenger growth; while costs per passenger have declined.

OMAB has the best balance sheet among the three publicly traded airports in Mexico, as well as the lowest exposure to tourism and international traffic. Net Debt-to-EBITDA has steadily declined, and even with the recent quarter’s hit stood at 0.4x, with no significant maturities until June 2021.

Negotiations for a new master development plan are currently in progress. We believe this is optimal timing considering that all key variables under consideration are currently under extraordinary pressure, and tariffs are likely to reflect these conditions.

Grupo Aeroportuario Del Pacifico

Grupo Aeroportuario del Pacifico SAB de CV (PAC) operates airports in the Pacific and central regions of Mexico. It is the largest of the three public airports in Mexico. PAC has a well-diversified asset base, with no airport representing more than 30% of traffic, a balanced mix of domestic (60%) and international (40%) traffic, and a healthy mix of business (25%) and leisure (45%) traffic. Its two largest airports – Guadalajara and Tijuana – are among Mexico’s most important manufacturing and industrial centers.

Nearly a quarter of revenues are denominated in USD. The company also has some of the best long-term investment opportunities, including a new terminal in Tijuana for US flights, significant potential for expansion in Cabos, and new hotels and parking lots.

Leverage remains manageable with little liquidity risk. During recent quarters, management cut all noncritical activities and services, suspended all distributions, and reduced the cost of service to around 40% for airports operating at minimum passenger levels. As a result, the monthly burn rate has been trimmed to MXN 315 million from a forecasted MXN 500 million. After a recent long-term bond issuance and draws on credit lines, cash and equivalents totaled MXN 15.7 billion at the close of Q2, which management estimates will cover 23 months of operating expenses and mandatory capex. Net-Debt-to-EBITDA stood at 1.1x at quarter-end.

PAC’s negotiations with the Mexican government concluded last year with very favorable economics. The agreed-upon 14% real increase in maximum tariffs should cushion this year’s decline in passenger traffic. Management is currently negotiating with authorities to defer investments through the first half of next year. Like ASR, under the current MDP, PAC has the option to reopen the entire agreement if Mexican GDP were to decrease by 5% or more.

Airports are a unique asset. They offer long-term investors inflation-protected cash flows generated from near-monopoly positioning, driven by historically resilient traffic growth, which has compounded at rates in excess of 2x global GDP. The current low-interest rate environment, combined with the industry’s attractive fundamentals and a relative scarcity for quality infrastructure investments, has only increased their demand over time. Yet supply remains limited.

Pension, sovereign wealth funds, and other institutional investors generally prefer to hold mature infrastructure investments for the long-term, given their predictable and growing distributions. Since many airports are already in the hands of “permanent capital” and unlikely to hit the market any time soon, the scarcity value of these premium assets has driven valuations higher. As a result, we have seen airports transacting at increasing multiples over time.

In the period after the September 11th attacks in the US, the EV/EBITDA multiples on airports rose toward 25x (chart below). Following the financial crisis in 2009–2010, multiples declined to 16x – 18x as deals stagnated due to lack of financing, reduced confidence, and gaps in valuation expectations. But it didn’t take long for M&A activity to pick back up along with valuations. During 2011–12, average multiples rebounded to above pre-crisis levels. More recently, transactions in the two years prior to COVID averaged 22x EBITDA.

We don’t expect a return to the lofty multiples seen at the beginning of the century anytime soon. But we don’t think today’s bargain prices will be around for too long either. Over time, we think we’ll see mature airports again transact at multiples of 10x – 14x. And since airport valuations are driven primarily by passenger growth, we believe that airports with higher traffic growth, like those in Mexico, deserve to trade at a premium. We would expect that airports with strong competitive positioning and long runways for growth to transact at multiples of 14x – 18x, consistent with the range they’ve traded at over the past five years.

Many factors impact an airport’s value. In addition to competitive and market dynamics, each airport’s operations and circumstances are unique, so investors must assess multiple inputs.

- Maturity. While large, mature airports may have less upside potential in passenger growth, they are also less vulnerable to customer concentration.

- Yield Improvement. Airports with lower non-aeronautical revenues than peers may be able to boost earnings by improvements in retail offerings, increasing parking fees, etc.

- Regulatory Environment. Airports are subject to different regulatory environments, with different limitations on returns generated from their regulated asset base (RAB).

- Capacity Constraints. The extent to which an airport has penetrated its catchment areas and limitations due to runway or terminal capacity will impact potential traffic growth.

- Traffic Mix. The makeup of an airport’s traffic mix – short vs long haul, business vs leisure, domestic vs international – can have a significant impact on earnings power.

- Customer Dependence. An airport highly dependent on one or two key customers will have less pricing power and greater risk than an airport with a more diversified customer base.

While each of these factors must be carefully considered, the confluence of these variables results in a range of growth and margin profiles for airports across the globe. And in general, those assets with better growth prospects and higher margins trade at a premium to their peers.

On this basis, Mexico’s airports appear to be in a league of their own, with best in class revenue growth and profit margins. Consequently, airports in Mexico have historically traded at a premium to many of the highest quality infrastructure assets in the world. But not today.

Despite these favorable characteristics, Mexico’s airports trade at extremely modest valuations today. Given the growth outlook and margin profile of these businesses, we would expect the stocks to trade at the higher end of the global peer group.

For reference, consider that the sale of Greece’s 30% stake in Athens International Airport was expected to trade for EUR 1 billion just a few months ago, implying an EV of EUR 3.3 billion. This figure is not far from the current EV of ASR, which does about 75% more revenue than Athens on ~ 40% more passengers. Given the delta in revenues between the two, it’s safe to assume that ASRs margins and growth profile are better as well. So back of the envelope, this would suggest ASR is worth at least 2x where it is currently trading to a private buyer.

It has historically taken 4-6 years for traffic to normalize following a recession or other economic shock. Following previous crises In Mexico, passenger traffic has recovered within 1-2 years. Most estimates we’ve seen are calling for a full recovery no sooner than 2023. While that would still result in a very attractive IRR on our investment, we don’t think the stocks will take that long to rerate. Once the market has greater visibility around a potential vaccine and the pace of recovery, we believe these assets will quickly return toward their long-term average valuations.

We believe that these airports will again trade at 14x – 18x, in line with previous transactions for premium infrastructure assets, representing 100% – 200% upside from current prices. If we take the low end of that estimate, and assume we reach 2019 EBITDA levels by 2023, an investment today would yield a 25% compounded return. If it takes five years to recover fully, our IRR would still be a respectable 15% annualized. We don’t think it will take that long.

No investment is without risk. Although we believe we are being well compensated to take these risks, here are a few of the things that we worry about:

- External events. While most of these black swans are unpredictable by definition, the damage caused by extreme weather, terrorism, or say a global pandemic can come fast and furious. Yet history has illustrated that time and again, volumes have quickly returned to trend, and continued growing.

- Political risks. Given the existing regulatory structure, a less friendly administration could negatively the earnings power of airports. That said, the importance of travel and tourism to Mexico’s economy is likely to prevent significant disruption to operations, and two of the three airports have already negotiated favorable terms, evidence of their constructive relationship.

- Low-cost carriers. Passenger traffic in Mexico has significantly benefited from the growth of low-cost carriers. Any reversal of this trend or issues with these carriers would weigh on future growth. While airline bankruptcies can have a short-term impact on airports, revenues are generally not correlated to which airlines are flying.

- An unstable US relationship. A slower than expected US economic recovery could weigh on vacation travel to Mexico and impact the Mexican economy. At the same time, there always exists the potential for future trade spats between the two countries. That said, a new administration at home is likely to reduce this risk.

Bottom Line

Looking beyond the current crisis, all of the factors that have contributed to the long- term growth of air traffic are likely to remain in place. The demographics of emerging economies, a growing global middle class, the millennial generation’s propensity for travel and experiences, and the continued growth of logistics to support e-commerce, all ensure that airport services will remain in demand for some time.

Today’s short-term dislocation presents investors with an opportune moment to deploy capital into high-quality infrastructure assets for long-term value creation. With interest rates falling into negative territory around the world, the demand for yield should ultimately drive up the valuation of airports with large, growing distributions.

Over the past five years, Mexico’s airports have satisfied investors hunt for growth and yield. PAC, ASR, and OMAB have compounded sales at 24%, 23%, and 18%, respectively, and yield 5% – 6% based on their most recent distributions (which are likely to be temporarily suspended).

In today’s low growth and low interest rate environment, this long track record of stable cash flow generation and increasing dividends should eventually capture investors’ attentions once again.

References & Resources

- Aamadeus, Reinventing the Airport Ecosystem 2012

- ACRP, Considering and Evaluating Airport Privatization, March 2012

- Airbus, Global Market Forecast, 2019-2038

- Boeing, Commercial Market Outlook, 2019-2038

- European Commission, Annual Analysis of the EU Air Transport Market March 2017

- German Airport Performance, The Market power of Airports, July 2008

- HEC Paris, Analysis of the Current Valuation of Infrastructure Assets, June 2017

- IATA, The Case for Independent Economic Regulation of Airports, February 2007

- IBID, Economic Briefing, The Impact of Recession on Air Traffic December, 2008

- IBID Vision 2050 February 2011

- ICAO, State of Airport Economics, 2014

- IBID, Long-Term Traffic Forecasts, April 2018

- IBID, Airport Economics Manual, 2020

- Journal of Transport Literature, Abuse of Dominance in the Airport Sector, June 2011

- OECD, The Impacts of Globalisation on International Air Transport Activity, November 2008

- OECD, International Transport Forum, Airports in the Aviation Value Chain, May 2013

SimpliFlying , The Rise Of Sanitised Travel, April 2020 - World Bank, Airport Development & Public Partnerships, April 2015

See the full article here.