Askeladden Capital Partners letter to investors for the fourth quarter ended December 31, 2019, titled, “Breaking Bad.”

(spoiler alert)

Jesse P: I was thinking about that thing you said about the universe. Going where the universe takes you? Right on. I think it’s a cool philosophy.

Jane Mg: I was being metaphorical. It’s a terrible philosophy. I’ve gone where the universe takes me my whole life… it’s better to make those decisions for yourself.

– El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie

Q4 2019 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Dear Partners,

Askeladden Capital Management has reached ~$50 million in committed capital – overwhelmingly from SMAs – and is therefore closed to new additions of capital from both existing and prospective clients, other than some I’ve discussed with specific clients over the last few months. Our actual fee-paying asset base (FPAUM) comfortably exceeds $20 million as of the time of this writing, including a mid-seven-figure amount of deployed institutional capital. We expect the remaining amount to be contributed over the next 18-24 months, overwhelmingly by two $1B+ institutional investors, as well as one existing Askeladden client that has been with us since 2016.

As a result, over the past month, we have been informing new prospective clients that we are full, and, as one of our clients suggested, putting their names down on a waitlist to allow us to efficiently fill any capacity that may open up in the future. To protect client interests given our increasing size and our illiquid small/micro-cap focus, we will discontinue public disclosure of actual and pro forma FPAUM, other than annual updates as required on Form ADV.

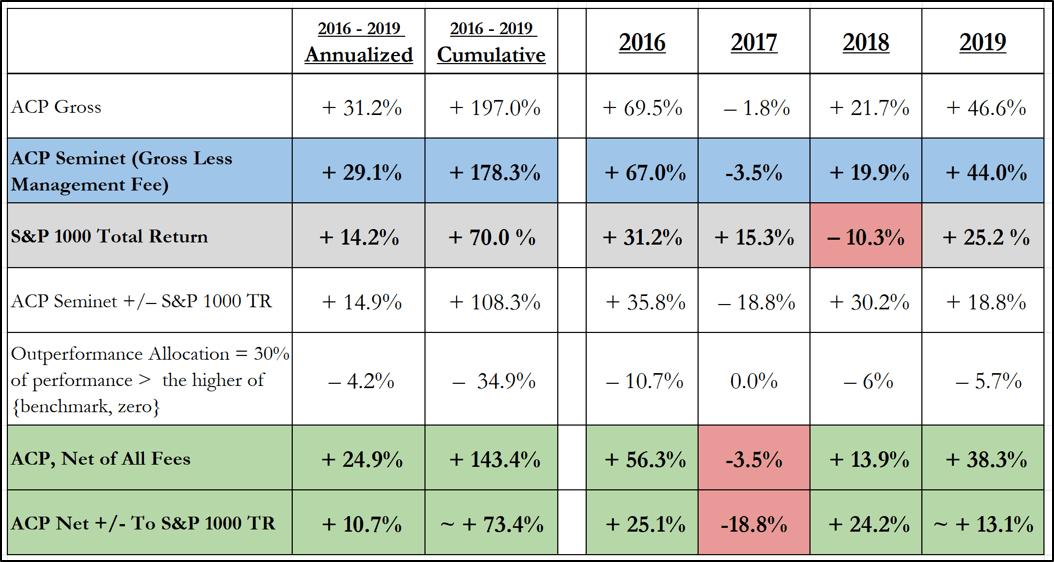

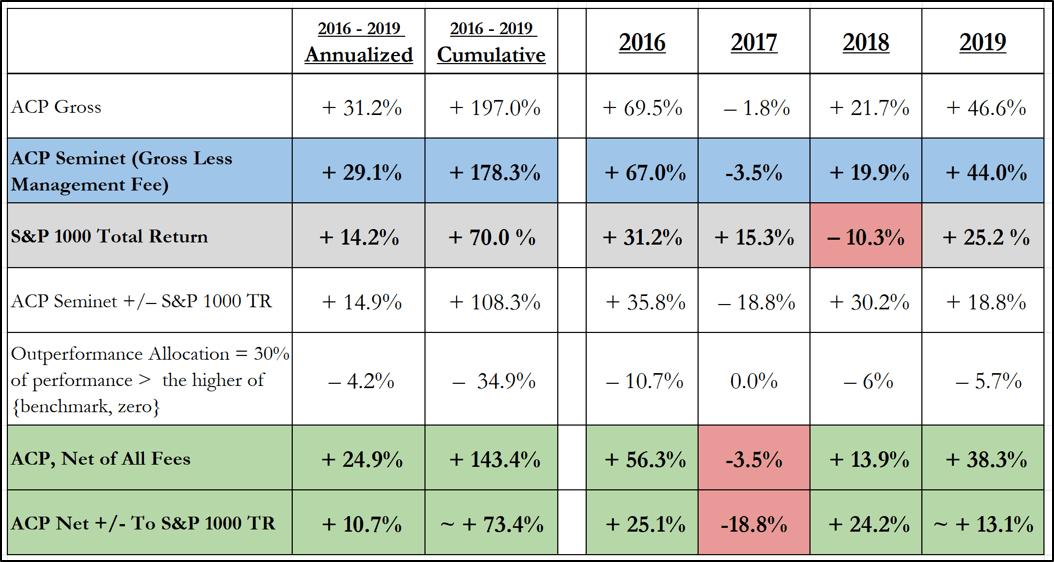

2019 highlights how near-term performance doesn’t tell the whole story. Although reported performance was very strong, with gross/net returns of over +46%/+38% (see performance table along with important disclosures in the appendix), my new-research productivity suffered. As has been discussed in previous letters, we did a lot of good sustaining work, efficiently converting watchlist candidates into actual investments as we monetized prior portfolio positions. As a result of that work – enabled, of course, by work conducted in previous years to build the watchlist – our portfolio is in excellent shape today. I remained unsatisfied at year-end, however, with how few new businesses we added to the watchlist during 2019.

Given the natural churn that occurs over time - for example, from businesses being acquired, or stories changing for ways (better or worse) that make them less likely to be investable for us – it is important that we constantly refresh the watchlist. Of securities in which we’ve made major purchases in the second half of 2019 and first half of 2020, only a handful were new names we’d found in 2019. Others were names we’d first worked on in 2018, 2017, and even 2016. Considering how our process works, lackadaisical new-name research efforts are unlikely to impact near-to-medium-term performance, but will provide us with a less robust opportunity set in the longer term.

Candidly, Askeladden’s rapid asset growth during 2019 contributed to this phenomenon. We actually didn’t spend much time on marketing calls or materials preparation for institutional clients; our third-party marketer, Maury McCoy (who gets credit for both of the institutional investors), handled most of this work for us. However, in addition to Maury’s efforts, we organically raised eight figures of new capital from over 40 separate clients ranging from small individual investors to sizable family offices and a charitable organization. All of this organic interest was inbound; i.e., we never sent a single cold email – all of this capital found us, often through letters such as this one.

While we are profoundly grateful for each and every single client that decided to entrust us with their hard-earned capital, this process did involve much administrative work, such as passing paperwork back and forth, going through the account onboarding process, and finally, placing trades to allocate new capital (which sometimes arrived in multiple small-dollar tranches that nonetheless required the same amount of work as larger ones).

In 2020, we expect – alternatively phrased, demand of ourselves – that in the absence of such non-recurring distractions, we make far more progress on gross adds, which we view as a lead measure KPI for our future success. Indeed, since the beginning of the year, we have already added 5 new stocks to the watchlist, with work on a sixth to be completed this week. We have sustained this level of progress despite a meaningful time commitment required to onboard our first institutional capital, a mid-seven-figure amount of which we now have deployed.

The balance of this letter will address several topics. First, and most importantly, why we’re sticking to our guns and closing to new capital at $50 million in committed FPAUM. Second, how we expect this development will impact our investors, with regards to both our communication and our investment strategy. Third and finally, we’ll provide a few highlights of how we’re utilizing our newfound resources to improve our process, and provide a recommendation for a talented investment analyst candidate along the way.

1. Breaking Bad: The Empire Business

Askeladden Capital Partners has long committed, loudly and publicly, to closing to new fee-paying capital at $50M to preserve our runway for investing in small, illiquid opportunities that others are forced to overlook. Clients, generally, are very pleased with this. My friends and family? Not so much. One of my friends casually mentioned offhand, “you know, you could always pause for a while and reopen to additional assets later.” (?!) Many investing friends – not to mention my parents – think I should keep raising capital until I reach at least $100 million, and maybe beyond.

There are a number of reasons I don’t plan to do this, but let’s start with the most important. Professional investors often have a distaste for management teams that are “empire-builders” – i.e., focused on increasing the size of their businesses, for the sake of ego or money, even though it’s not the best thing for shareholders. Ironically, many asset management firms function in exactly the same way, raising far more assets than they should, just because they can.

I’ll never forget something I learned as an analyst, many years ago. I saw a news article about how a famous fund manager – the kind whose grandchildren’s grandchildren will still be naming buildings – was launching a number of new products and rapidly growing his AUM. Around the same time, I saw an interview he gave, in which he professed that his greatest joy was sharing his favorite hobbies, places, and experiences with his children.

I asked someone I knew in the industry – a personal friend of his – how much time this manager actually spent with his family. Their response? “Almost none. He’s way too busy.”

The point is, empire-building can have consequences. Let’s go back to S5 E6 of Breaking Bad, “Buyout” –

ALBUQUERQUE, 2012: Walter White and his business partners, Mike and Jesse, have stolen 1,000 gallons of a meth precursor chemical, methylamine, from a train. A preteen boy was murdered in the process. A meth-cooking competitor wants to buy their whole supply of the precursor, and is offering Walt $5 million for his share. Walt refuses to sell, because 1,000 gallons of methylamine, cooked, turns into $300 million of crystal methamphetamine. Jesse tries convincing Walt to see the light.

HEISENERG: Pennies on the dollar, Jesse, and that’s what you’re going to sell out for? Pennies? Why?

JESSE PINKMAN: Five million isn’t pennies. It’s more money than I’ve ever seen. And when it comes down to it, are we in the meth business, or the money business?

[later] When you, uh, when you started this thing. Did you ever dream of having 5 million dollars? I know for a fact that you didn’t. I know for a fact all you needed was $737,000. Because you worked it all out, like, mathematically… you could spend time with your family, no more worrying about them getting hurt…

Isn’t this what you’ve been working for? … I don’t know how else to say it, Mr. White. 5 million dollars isn’t nothing…

HEISENBERG: Jesse, you asked me if I was in the meth business or the money business.

Neither.

I’m in the empire business.

Subsequently: Walter White watches as his brother-in-law Hank is murdered, as a result of his actions, and watches the majority of his money stolen. His only friend, Jesse Pinkman, is tortured and enslaved as a meth cook, also as a result of Walt’s actions. He thereafter loses the affection of his wife and son and is forced to flee, leaving them and his infant daughter behind, as the police hunt for him. As a result of Walt’s actions, his family becomes destitute. After exacting revenge on his remaining enemies, Walter White dies, friendless and alone, in the ruins of the empire he built.

OMAHA, 2018:

WARREN BUFFETT: It’s insane to risk what you have and need, for something you don’t really need.

Walt didn’t start Breaking Bad as the villain. He was just a kind, respectable high school chemistry teacher, dying of cancer, whose meager life savings would be zeroed by an aggressive tumor. He just wanted to cook a couple batches of crystal, to leave something for his family. $737,000, to be precise, because he worked it all out, like, mathematically.

But his choices – and outside forces – drew him deeper and deeper into the drug trade, fulfilling the cryptic Batman prophecy (“you either die a hero, or live long enough to see yourself become the villain.”) Walt had many opportunities to walk away. Instead, he chose to build an empire.

Agency is not always a bright line, of course. As we know, many psychological phenomena – social proof, loss aversion, contrast bias, and so on – shape our choice architectures. If we’re not careful, we can find our decisions being made for us rather than the other way around; in the case of Breaking Bad, many of Walt’s decisions were driven by necessity or desperation. To protect himself and his family, Walt had few choices but to orchestrate the murder of Gale Boetticher – and, subsequently, Gus Fring. To prevent his son from finding out the truth and his family from being left destitute, Walt had little choice but to blackmail his brother-in-law, ASAC Hank Schrader. Individually, each of these decisions is understandable – possibly even defensible.

But the broader pattern of behavior is neither understandable nor defensible, and that is how Vince Gilligan and the writers of Breaking Bad intended it. At what point on the slippery slope does Walter go from being the hero to the villain? Every time Walt was given a chance to extricate himself, he chose instead to get more entangled. Until the pivotal scene quoted above, his partner Jesse followed the same path: instead of making the right (difficult) choice for himself, he took the easier path of going with the flow. Going where the universe (Mr. White) took him.

It’s better to give the universe the middle finger, maybe even two, and tell it you’re not going where it takes you.

It’s better to make those decisions for yourself.

So: this is exactly the point in an asset manager’s life-cycle where the universe tends to take you on a path of expanding assets. A few years ago, I might’ve sold a kidney (not really) to scrape together another $2 million in FPAUM. A few weeks ago, an institutional investor planning to invest an 8-figure sum of capital in Askeladden Capital Partners sent me an email asking if it would be “agreeable” with me if they upsized their proposed investment by $2 million (an addition equivalent to our entire FPAUM base at one point in 2017). A few years ago, I jumped at the sight of every new inbound lead, because they didn’t arrive that frequently. In recent months, I’ve often received so many that I fall behind on answering them for weeks or months, since I needed to focus on research for the clients I already have.

Success begets success; now that we are at a “critical mass” where we have respectability and enough resources that we’re considered viable and sustainable, all of a sudden far more people are interested in the same process and same track record (more or less) that we’ve had for a while. It’s not a coincidence that our FPAUM growth accelerated over the course of 2019, from below $5 million at the start of the year to $10 million in H2 2019 to over $20 million today (with much more to follow). We are aware of another small-cap shop that, a number of years ago, was at a similar juncture to us, and decided to upsize from their historical closing target to an amount much larger, because they had fund-raising momentum and demand from prospective investors.

With a short-term time horizon, raising more assets would undoubtedly make sense. I’d make a lot more money. But from a long-term perspective, it makes far less sense. While the perception of our attractiveness as a prospective investment has changed, nothing fundamentally has changed. I’m still the same person who doesn’t want to manage a large team or spend a lot of my time on operations, compliance, and client management. I still firmly believe that our returns are half process/skill, and half opportunity set – nothing has magically changed about the small-cap universe that will allow us to effectively manage an eventual capital base of $300 million plus rather than $100 - $200 million (this latter figure assuming half a decade to a decade of organic growth from compounding $50 million.)

So this isn’t the time for the thesis drift that many asset managers start to suffer from, regarding their own business. We remain firm in our commitment to close to new capital from existing and new clients alike. We may continue to accept small-dollar amounts of capital from friends and family on a non-fee-paying basis (we are in the process of converting most of our existing friends/family accounts from fee-paying to non-fee-paying in this regard as well, to thank these investors for their support and generate incremental capacity to meet demand from new clients), and will honor our promises made in the last few months to a number of prospective retail clients who wished to invest small-dollar amounts as well. Depending on the market’s performance on any given day, this may take us to a rounding error above $50 million (say, $51 or $52 million). But beyond that, for us, the right choice is to walk away from, rather than towards, the capital which we could undoubtedly raise.

This decision may seem curious in the short term – our friends, like Walt, are only focused on the money we’re leaving on the table. We’re, instead, focused on the longer-term. Askeladden as it exists today is exactly what I wanted it to be: a low-overhead, lean investment operation that, going forward, will allow my time to be focused almost entirely on adding value to clients through investment research, while generating an income that is sufficient to support a reasonable (albeit not lavish) lifestyle for a future family, and providing me with control over my time.

Were we to continue to scale over the next few years, we would instead see a repetition of the research-productivity issues that cropped up in 2019, and/or necessitate a more “formal” organization structure (involving mission statements, healthcare plans, and perhaps most pressingly, someone to design Q4 Investor Letter cover pages that don’t look like a kindergartener got loose in MS Paint. Jokes aside, Maury is actually very good at graphic design, as evidenced by our pitchbook, but we stubbornly insisted on doing this one ourselves.)

One of our clients is fond of mentioning that “John Henry died in the end,” and the same is true of Walt – and of many (most?) asset managers. I used the word life-cycle very intentionally, because many of you who’ve been in/around the industry are acutely aware of how many funds scale up rapidly, find they can’t manage hundreds of millions (or billions) of dollars as easily as they thought they could, and then are forced (often by poor performance and subsequent client redemptions) to go out of business or significantly reassess their business strategy.

One of our clients – a long-tenured industry professional – recently made the following, Mauboussin-like relative-skill observation about this phenomenon:

There are lots of bright investors, but usually what happens is those that are bright and capable do well, gain the attention of others, grow AUM, and then compete in the big league… It isn’t simply about how good or smart you are, it is more about how good and smart you are relative to those you compete with.

Since I’m trying to run Askeladden for a decade or more rather than for a few years, my focus is obviously on ensuring that this Breaking Bad, boom-bust pattern doesn’t befall us – I’m perfectly happy to trade lower near-term cash flows for a higher probability of having a sustainable business for the long-term. We feel lucky and thankful to have reached this stage, and we’re intent on not screwing it up.

I want to end this section with some caveats. Remember that the theme of this letter is personal choices. I would like to point out that while closing Askeladden to new capital at ~$50MM of commitments is the right choice for us, that doesn’t mean it’s the right choice for everyone else. In fact, although we believe that empire-building is often the motivation for many asset managers to scale up, this is certainly not the only reason that many make such a choice.

Setting profit motive entirely aside, there are many valid and defensible reasons that one might wish to scale a business far beyond the extent to which I intend to grow Askeladden. First, while a business like mine has no terminal value (it cannot outlive my capability and enthusiasm for the work I do), a larger organization can grow and evolve decades or even centuries after its founder is gone, adding value for clients, employees, and the world at large. Second, larger organizations also have the resources to solve challenging problems – my approach, less noble than profitable, is to simply avoid hard problems, notwithstanding that they may desperately need solutions.

Finally, larger businesses create more value (for everyone) in total dollar terms. It is humbling to realize that in terms of aggregate value added to clients, 200 basis points of outperformance on a $1 billion dollar asset base ($20 million) is 4x 1,000 basis points on a $50 million asset base ($5 million). In other words, percentages are not all that matter; as a friend of mine recently observed, 20% of something is better than 100% of nothing.

It bears noting that the two institutional clients who’ve made commitments fall into this category given their $1B+ asset bases. While I would certainly hope that on a percentage basis, Askeladden’s outperformance far exceeds that of these clients’, I am acutely aware that much smaller figures on their end move much bigger needles in terms of funding valuable endeavors – so I have great respect for those who can effectively generate outperformance on large asset bases. It is, in fact, this respect that causes me to not want to compete with such people, instead picking at the opportunities that are generally too small to be worth putting through their sharp processes and refined judgment.

As our client referenced, it’s about relative and not absolute level of skill, and we try not to forget this. By inversion, a mediocre NFL team would still win a high school or college championship – you don’t have to be very good if your competition is worse. We’ve simply decided we’d rather go 15-1 in the minor leagues than 8-8 in the major leagues, so our strategy is to play as many games as possible in the minor leagues (small / micro-caps), only competing in the major leagues (larger, more liquid companies) when it’s a layup.

2. The Askeladden Business

This section aims to address two questions I’ve received regarding our approach going forward.

The first deals with communication: now that we’re at scale, do we plan to continue to publish our letters, specifically the public letters?

The answer is: yes, with caveats. The purpose of the public letter has historically generally been twofold: one, to educate existing and prospective investors about Askeladden’s process, and two, to provide me with an opportunity to crystallize my thoughts.

Existing investors, at this point, seem to understand Askeladden’s process pretty well (with the occasional exception as I touch on below); meanwhile, there is no longer any real need to communicate to prospective clients. Therefore, my expectation is that public letters will be briefer going forward. To save time and reduce compliance risk, I will likely also choose to report returns publicly on only an annual basis, as clients can access their returns themselves, and quarterly performance doesn’t mean much in our business.

On the other hand, I intend to put the same amount of time and effort into the private, clients-only portfolio commentaries, which have been very well-received by clients. To my knowledge, few investment managers provide such a thorough quarterly breakdown of investment decisions on a position-by-position basis, and I hope that this “show don’t tell” approach lifts the majority of the freight in terms of helping investors assess our decision-making on an ongoing basis.

This also saves us a significant amount of time and levels the playing field. Typically, how IR works (whether for public companies or asset managers) is that large holders get calls with management where all their questions are answered, and smaller “retail” shareholders are left in the dark. We believe that this process is both A) inefficient (as it consumes a lot of management time to answer the same question in 10 different calls rather than 1 written document), and B) unfair (as smaller shareholders don’t get access to the same useful commentary.) Our solution to both of these problems is to provide the most comprehensive overview we can, in written form, to all clients – obviating the need for frequent update calls, and ensuring everyone understands why we’re doing what we’re doing. It’s the equivalent of an “Analyst Day” transcript from a public company, just every quarter.

Moving on: with regards to our process and strategy, one of the questions we’ve received from time to time from a small but vocal minority of prospective and actual clients regards our turnover (with an explicit or implicit implication about the tax burden that such an approach generates).

Let’s level-set. Although, from a valuation standpoint, we underwrite investments with a long-term horizon, we are not conceptually buy-and-hold investors. In our worldview, an important part of being a value investor is constantly evaluating our holdings against our opportunity cost of capital – the opportunities available on our watchlist. To the extent that our process works, and consistently surfaces names that have a better price/quality ratio than things we already own, then we’re more than happy to make that tradeoff. If we bought something at $10, thought it was worth $15, and now it’s trading at $13 while we have the opportunity to go buy some other (equal-quality) $15 fair value for $10, or a much higher quality $15 for $12, we are going to be trimming the $13 stock to add to something else – end of discussion. Echoing the theme of this letter about personal choices, this, again, is not necessarily the right strategy for everyone, but it’s the right one for our temperament and process.

A necessary corollary to this is that our tax burden tends to be somewhat higher, proportionately, than funds with less turnover. We would note that our returns have been very strong since inception, and we’re proud of them even on an after-tax basis; we would also note that in environments where our returns were less-good (i.e., stocks we owned went up less, or more slowly), then we’d be less likely to generate high turnover and thus taxable events, as our tax generation is – most of the time – a result of something in our portfolio having done well. Lower tax burdens are not a free lunch. Lower taxes at the necessary cost of lower returns would not, in our view, be a good outcome for clients, but it is nonetheless something that a certain subset of the investing world views as a preferable outcome.

We like our approach, and we also think it does the most good for most of our clients. The two institutional investors we referenced are tax-exempt; one is a private mission-driven foundation, while the other is an OCIO whose clients are all non-profits. We have another seven-figure client that is a charitable entity, and several clients (including a family office) from international jurisdictions where U.S. taxes are either not due, or the local tax regime specifies no difference between short-term and long-term capital gains. Beyond this, a reasonable portion of our individual investors have made their investments through tax-sheltered vehicles such as IRAs.

That leaves our fully-taxable U.S. based investors – a significant minority of our committed capital base. The vast majority of these investors – including, importantly, myself – are more focused on total after-tax returns, than they are on arbitrary turnover figures, or the size of their tax bill independent of how much they’ve earned on a fully-net basis.

Although, in rare and select instances, we will hang onto something in taxable accounts while selling it in tax-exempt accounts, we generally find it more complicated than it’s worth to try to optimize for too many things at once, and we don’t think it’s in anyone’s best interests long term for us to try to run a tax-optimized strategy and a non-tax-optimized strategy Although I fundamentally disagree with excessive focus on turnover and taxes, if everyone agreed with me about all investment-related things, then I’d be out of a job – and I’m not always right, anyway.

So, I wanted to take this opportunity to make clear the approach that we use, for better or worse, and my continued commitment to that approach. To the best of our knowledge, the vast majority of our clients are onboard with our approach. A handful may not be, and we’re okay with that – we can’t be all things to all people. If you vehemently disagree with my approach, I don’t hold it against you.

To the extent that any client feels that our value-maximizing approach is not appropriate for them, and they prefer a tax/turnover-focused approach, I understand – they are entirely welcome to seek more appropriate alternatives elsewhere, as a number of prospective clients (not to mention existing clients) await to backfill any withdrawals. Since it’s all the same on my end from an FPAUM standpoint, I would rather have 100% of clients be fully satisfied and onboard with our strategy: if anyone has even the slightest doubts, now is a great time to move on to greener pastures.

3. The Watchlist Business (and an analyst candidate recommendation!)

Our number-one priority this year (other than, of course, thoughtful portfolio management) is adding to our watchlist. As has been discussed rather extensively in previous letters, we are very confident in the current portfolio, but know that to have a robust opportunity set in 2021, 2022, and beyond, we must build a list of prospective candidates into which to deploy harvested capital.

I am going to keep my comments here relatively brief, as I don’t want to give away the “secret sauce” for generating attractive investment candidates, particularly as some of our approaches here are very specific. I will provide more commentary to this end in future portfolio commentaries as some of these companies end up in our portfolio.

However, I think it is generally well-understood that we have a “type” – we know what sorts of businesses we find interesting. Generically, they often have quality factors such as high margins, high recurring revenues, clean balance sheets, limited cyclicality, a secular growth trend, etc. In thinking about our research process and the bottlenecks / value-add, we’ve realized that identifying companies that might have such criteria is generally not something we need to spend our time on, as it is an activity that can easily be replaced (or at least substantially sped up) by someone else.

What we cannot replace, however, is our own due diligence and analytical judgment process; no matter how much we trust a source (ex. Zeke), we still have to do all/most of the work ourselves to get comfortable.

The logical conclusion is to eliminate as much of our time spent on part A so that we can spend much more of our time on part B. There are multiple ways to do this. One is by starting with existing written material on companies – something that a lot of value investors consider heretical thanks to the risk of anchoring, but something we feel is appropriate for our process.

Particularly for companies with mediocre IR, it can often take hours (and sometimes days) to get to even a vague and preliminary understanding of what a company does, what its value proposition to clients is, what differentiates it in the marketplace, what the opportunity set is, what the historical track record of decision-making (both operational and financial) is, etc. Spending valuable research hours on such companies just to eventually find out that they fail many of the basic checkpoints is a wildly inefficient use of time.

Conversely, starting with some sort of writeup or overview on a company – even if very brief – speeds up this process dramatically. If someone pitching the company (buy-side, sell-side, doesn’t matter) can’t get us excited about at least the potential for the company to be interesting, then it’s probably not worth our time. We still have to read all the same documents and do all the same due diligence, but now there’s less risk that we’re wasting our time on a business that is, to begin with, profoundly uninteresting.

Moreover, at the conclusion of our process, we are rarely buying companies immediately anyway, and if we do, it’s only in small / starter type positions – usually providing us with many months or years to follow a story and update our priors before we ever actually consider a material investment. This reduces the risk of anchoring – and context matters, too: it gives us a much broader set of companies to look at and evaluate, allowing us to objectively compare prospective investments to our opportunity cost of capital. We’re increasingly searching out such write-ups (sometimes on a paid basis) in a systematic and organized way. I’ve found a very interesting set of sources (including free sources) of such materials that I haven’t heard of many other people using; as such, I don’t want to disclose it.

There are a number of our portfolio companies that we haven’t seen written up anywhere for a long time, or that have only been written up after we’ve already done our research and followed/owned them for years. But it’s important not to be overly dogmatic. Some of our best investments have been ones we’ve initially heard about from friends, or seen first somewhere else.

One example: we never would have made our extremely successful investment in Australia / New Zealand apparel brand Kathmandu (ASX:KMD) without discovering KMD through an excellent writeup by Singapore-based professional investor Douglas Lim of Whitefield Capital. It took us many months to start researching KMD after his writeup, and much of our KMD position was built over a year after initially reading his writeup. Our efforts to date have resulted in over a hundred pages of internal documentation, and the idea is fully “ours” at this point. Nonetheless, we wouldn’t have encountered KMD without him. Interestingly, his post received far less engagement than many (worse) ideas, suggesting that even though this thesis was “out there,” few people were paying attention.

Of course, many of the juiciest opportunities are those that haven’t been pitched on popular investment sites, but there are ways for us to more efficiently surface these as well by partially outsourcing the “screening” stage of our research process (i.e., identifying names to work on). Enter our investment analyst recommendation: over the past month, we’ve been working with a recent University of Texas graduate who is passionate about value investing and eager to learn. We’ve been in touch with him for over a year, and from reading research that we’ve passed along, he’s developed a thorough understanding of our investment process and our “type.”

With a mandate from us (we had a hypothesis on a specific “type” of company that might be very investable for us and have a high probability of actually making it into the portfolio), we set him off on a project to identify companies that might meet this “type,” doing basic / brief research and valuation work to provide some commentary to prioritize which ones are higher priority for our full due diligence process.

This project contributed to two of the five companies we’ve added to our watchlist so far this year, one of which we’ve already taken a small bookmark/starter position in, and undoubtedly it will contribute to many more over the course of the year. He’s also been creating Askeladden-style comprehensive research documents – more for his own personal edification than anything else (these generally aren’t commissioned by us; he’s doing them for fun and learning) – and I think you’ll be impressed with the quality of these documents relative to his age and experience level.

As pleased as we are with this individual’s project work for us, the nature of Askeladden’s investment process and business unfortunately does not lend itself to hiring a full-time analyst – so as much as we’d like for him to stay available for occasional projects, we’re trying to help him find a role he very much deserves somewhere else. Several years ago, a similar call-out in one of our letters landed a former Askeladden intern an analyst role with a family office that has worked out well for both parties over multiple years, so I figure it’s worth another shot.

Although this individual strongly prefers opportunities in Texas, he’s open to discussions about roles elsewhere if the fit is right, and I’ll take this opportunity to pitch the benefits of remote work (we met him in person once, but have since interacted seamlessly, exclusively via email). Perhaps the best recommendation I can provide is that we’ve already paid him a four figure amount for his work on this project – which is more like real junior analyst money, not $10-an-hour type intern pay, on an hourly-equivalent basis. If and when we come up with additional deliverables for him to work on, we’d be similarly happy to continue compensating him appropriately for his efforts.

Please reach out to me ([email protected]) if you, or your network, might have a full-time analyst role for such a self-motivated, talented, and high-integrity individual.

In conclusion, we expect to thoughtfully leverage our increased spending power to access resources that will speed up our process – whether this is by product subscription, commissioned project work, or so on. We continue to consider other alternatives to add value to our process as well, and are not scared of spending significant amounts of money if we believe it enhances our probability of success.

We are most focused, however, on ensuring that nothing we do compromises the process that has made us successful so far, so expect any enhancements to be incremental rather than revolutionary: their purpose is to make us better at what we do, not to change what we do.

We’re not going where the universe takes us. We’re making those decisions for ourselves.

Westward on,

Samir

Appendix - Performance Chart and Important Disclaimers

Results for each individual year are presented assuming that a hypothetical investor joined at the beginning of that year. Cumulative and annualized results are presented assuming that a hypothetical investor joined at Askeladden’s inception. Given our three-year assessment of performance fees, which may result in unaccrual of previous fees from a previous year, or a lack of accrual of fees in a given year if previous years’ results were below that of the benchmark, a long-term investor’s net returns in any given year may be different than the net returns stated here for that year, depending on the exact date of their entry.

Gross returns from inception through 12/31/2018 are audited. 2019 returns are unaudited; however, results that we report are rounded down slightly from official statements provided to clients by our fund administrator, which we sanity-check against brokerage statement reports. Please note as well that the Partnership’s inception date was approximately one week into 2016, but for convenience, we annualize results on the basis of a full year, which has the result of slightly lowering our reported annualized returns for the year 2016 from their actual value. Absolute 2016 SPTR1000 percentage performance is reported from the date of inception through year end.

SMA clients should also note that the returns discussed in this letter are only for Askeladden Capital Partners LP, and individual SMA account performance may vary due to tracking error, account parameter restrictions (such as international trading permissions), and other such factors. Fees are also reported for an investor paying the standard fee structure; investors paying a different fee structure (such as non–qualified clients to whom we cannot legally charge a performance fee) will obviously have different results, whether they are SMA clients or LPs of the fund. As such, please consult your own account statements to determine your individual account performance.

Moreover, please also note that investors in Askeladden Capital Partners pay a variety of fee structures – including my own capital, which pays no fees, and non–qualified clients on whose accounts I cannot legally charge performance fees. This means that Partnership–wide audited returns reflect a variety of fee structures, and this fee structure on average (factoring in, for example, my account not paying any fees at all) results in partnership–wide fees being materially lower than the stated fee structure.

Therefore, I believe it would be misleading to report the Partnership’s actual audited net returns in the table above, as they would materially overstate the returns that would have been achieved by a client paying the standard fee structure of a 1.5% management fee (assessed monthly in arrears) and a 30% performance allocation of any outperformance vs. our benchmark (assessed on every third anniversary of a client’s account funding or deployment). As such, instead, in these letters, I report my calculations for fees for a hypothetical investor paying our standard fee structure. Cumulative net results in the table above are thus materially lower than actual audited net results, but, in my estimation, substantially more useful for analytical purposes. Investors who pay different fee structures (for example, our non-qualified clients who pay a flat rate of 1.95%) will obviously have different net returns than the table above. Investors with any questions are welcome to review our audited financials for 2016 – 2018, and for 2019 when they become available (usually by late March or April), and, once again, clients are advised to rely on their individual statements from our Fund Administrator – or, in the case of SMA clients, their statements from Interactive Brokers – to understand their specific account’s performance.

Past performance is not a predictor of future results. We do not expect our future returns to approximate our historical returns. Amounts may differ due to rounding. Our benchmark is the S&P 1000 Total Return index, which was chosen because it had, at the time of inception, historically outperformed the Russell 2000 and most accurately represents our typical investment universe of small and mid–capitalization U.S. equities (i.e., those with a market cap of $10 billion or less). We may invest outside this universe (for example, in U.S. large caps or international small caps.)

This is not an offering of securities or solicitation thereof; any offering of securities would only be made to accredited investors via a Private Placement Memorandum under Rule 506(c) of Regulation D, and any prospective partners who did not have a pre–existing relationship with Askeladden as of 1/18/2017 would be required to verify their accredited status with relevant documentation. This requirement does not apply to separately managed accounts. Any documents prepared prior to 2017–01–18 were not intended for public distribution and should be read accordingly. Askeladden Capital Partners, and SMAs that mirror its strategy, should be considered high–risk investments suitable for only a small portion of an investor's overall portfolio, as they involve the risk of loss, including total loss. Specific risk factors are enumerated in our Form ADV.