Given the recent media coverage of the Royal Family, we pondered how family values might illuminate the inherent complexities in what seems to be a difference of beliefs and behaviors. As a coach of enterprising families, I can say that for families who own and manage assets together, shared values are essential for legacy families and their successful generational transfer[i]. Values conflict challenges family cohesion; however, values are not as visible as behaviors and beliefs. Instead, it is the behaviors, such as choosing to move or not partake in family activities that we see and experience, not always realizing or understanding the values that drive those behaviors.

The issue is not necessarily values conflict, as families often have the same values, but rather, values prioritization that erodes families from staying together. If, for example, my family has 12 values and we all agree on them, then that is great. Well, not exactly, because the value I hold dearest might be my brother’s number 12. He still believes that personal growth is important, but he may put family, tradition or nine other values before personal growth, which, in many cases, may still cause us conflict. It might be useful to discuss a values model, which explains why values are murky in families and organizations.

Q4 2019 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Values

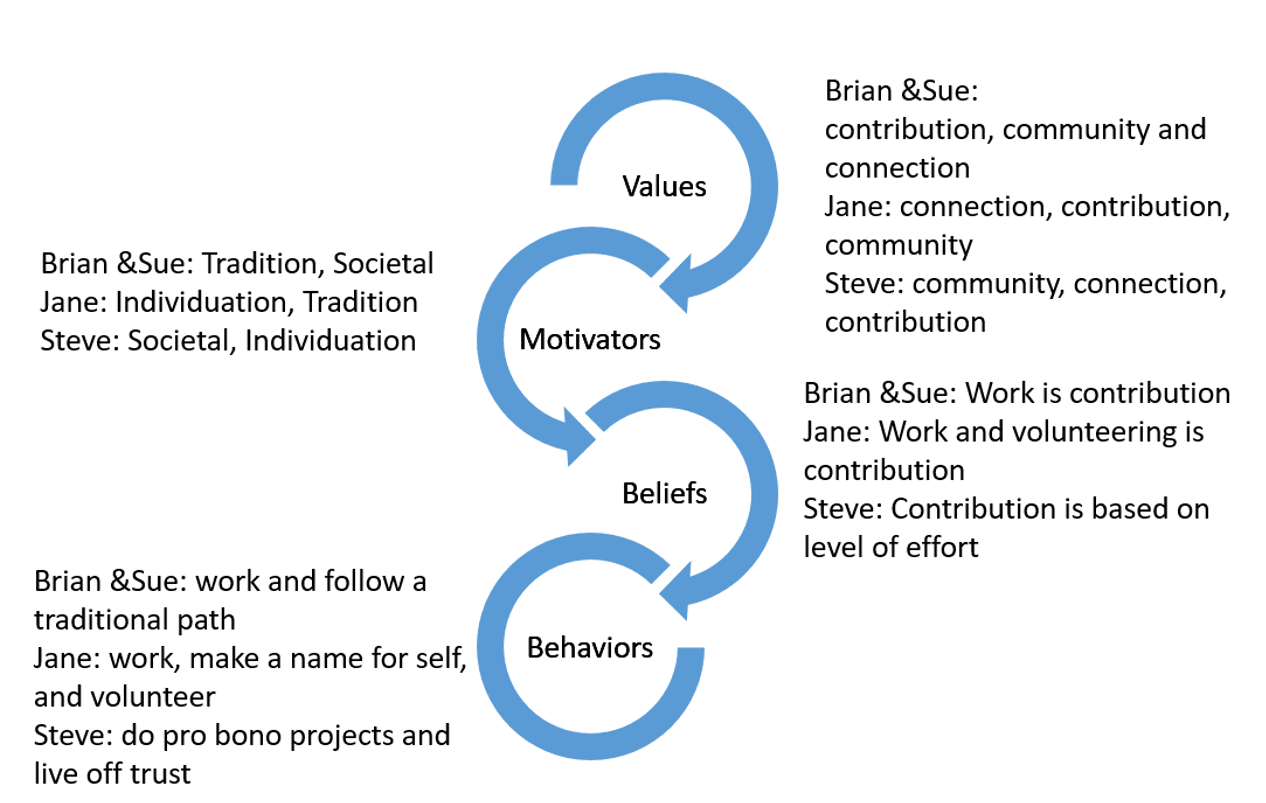

The graphic below shows a values model we have observed over time. Values as a concept has many definitions; we say that values are that which we hold most closely to who we are and how we ‘be.’ They inform our motivators, belief and behaviors. People often speak of core values. Interestingly, we do not see people’s values nor when in conversation with one another do we announce them. You might not say that you held the door open for the person behind you this morning because you value respect, however, you may say you believe in kindness. Seemingly a semantic difference, it demonstrates a nuance. Let’s define the other terms in the model before going through a couple of family examples.

Motivators

Motivators are our drivers that develop throughout our upbringing and may describe competencies. These are subconscious of behavior and are important to us. For example, you may be motivated by learning (knowledge), while your sibling may be motivated by earning (money), and you both may have the same top value of personal growth.

Beliefs

Beliefs are the thoughts was have about our world that we see as true. They are the meaning we make about the world. Your brother may believe that people fundamentally are out for themselves, and you may believe that people are generally cooperative. These motivators and values may still apply without impacting this belief system.

Behaviors

Behaviors are what we do with our values, motivators and beliefs. Ideally, we are aware and congruent people acting in accordance with our values, motivators and beliefs. There are days where I do something that at the time seemed like a good idea but later did not. That probably means I was out of alignment with myself in one of these three areas.

A Family Affair

The Adlers are a successful third-generation family that owns a manufacturing company, which has provided the family with steady annual returns. The second generation, which is now running the company, consists of Brian and his wife, Sue. Brian and Sue have two children ages 30 and 32, respectively. The elder daughter, Jane, was a successful lawyer who married an accountant. Their younger son, Steve, was a successful graphic designer who married a nonprofit executive.

When each adult child turned age 30, they were each given access to an annual trust of $60,000. Jane worked with her trustee to modify the investment strategy for the trust’s principle and occasionally took some proceeds to invest in real estate. Steve, upon receiving his trust, quit his job and started living off $60,000 per year, which was about half his previous salary.

When I spoke with the family, Brian and Sue were worried that Steve was not living up to the family’s value, and they did not understand why. They felt they raised him properly and modeled what was expected. They have always worked and wondered why he thinks it is okay not to work. After interviewing each family member, I found that all family members have the same three values: contribution, community and connection. That began a discussion between the two parents and two adult children as to how they can all have the same values, albeit in a different order, and still have one act so outside of what was considered acceptable. During that discussion, we reviewed the above model and applied it to the family question about contribution.

As you can see, the family did not have values-based conflict. They were being tied up in their beliefs and behaviors around contribution. In fact, all four had some overlap in their motivations. After a two-hour conversation, it was clear that the concept of contribution did not have to look like work that earned a paycheck, rather, it had to make a difference. Steve was doing wonderful design work for many nonprofits, and he and his wife could live on her salary and his trust more modestly, but with a larger impact.

It is hard to say if the Royal family is having a values conflict or a conflict around how those values are expressed through motivators, beliefs or behaviors. It is likely that they are not having the kinds of conversation that allow understanding and differentiating between these multifaceted layers and finding the fulcrum points to come together.

[i] Jaffe, Dennis: 2013 (August) Good Fortune: Building a Hundred Year Family Enterprise