The following is an except from Steven Klerck’s paper on “The Origins Of Value Investing Revisited.”

The year 2019 marked the 70th anniversary of the publication of The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham (1949). The seminal work has been described by legendary investor Warren Buffett as “by far the best book on investing ever written.” In contrast to Security Analysis (Graham and Dodd, 1934), The Intelligent Investor was written for the layman investor with primarily focus on investment principles and investors’ attitudes. Graham (1949) starts by delineating the difference between investing and speculation. Accordingly, An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and a satisfactory return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative. Based on this definition and the accompanying clarifications we deduce that in Graham’s investment philosophy investment risk equates with a permanent or long-term loss of capital. Graham (1949) states that there are two main causes to permanent or long-term capital losses: a) the purchase of low quality securities and/or b) the purchase of companies far above their tangible value, notably at times of favourable business conditions.2 Consequently, investment risk can be avoided and a satisfactory return can be realized through the purchase of quality securities at low valuations, i.e. through the adoption of the margin-of-safety principle. The principle is described by Graham (1949) as the central concept of investment or the secret of sound investment. However the adoption of the margin-of-safety principle does not imply that the investor will avoid short-term price declines; declines of up to -50% should be psychologically taken into account.

Q4 2019 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

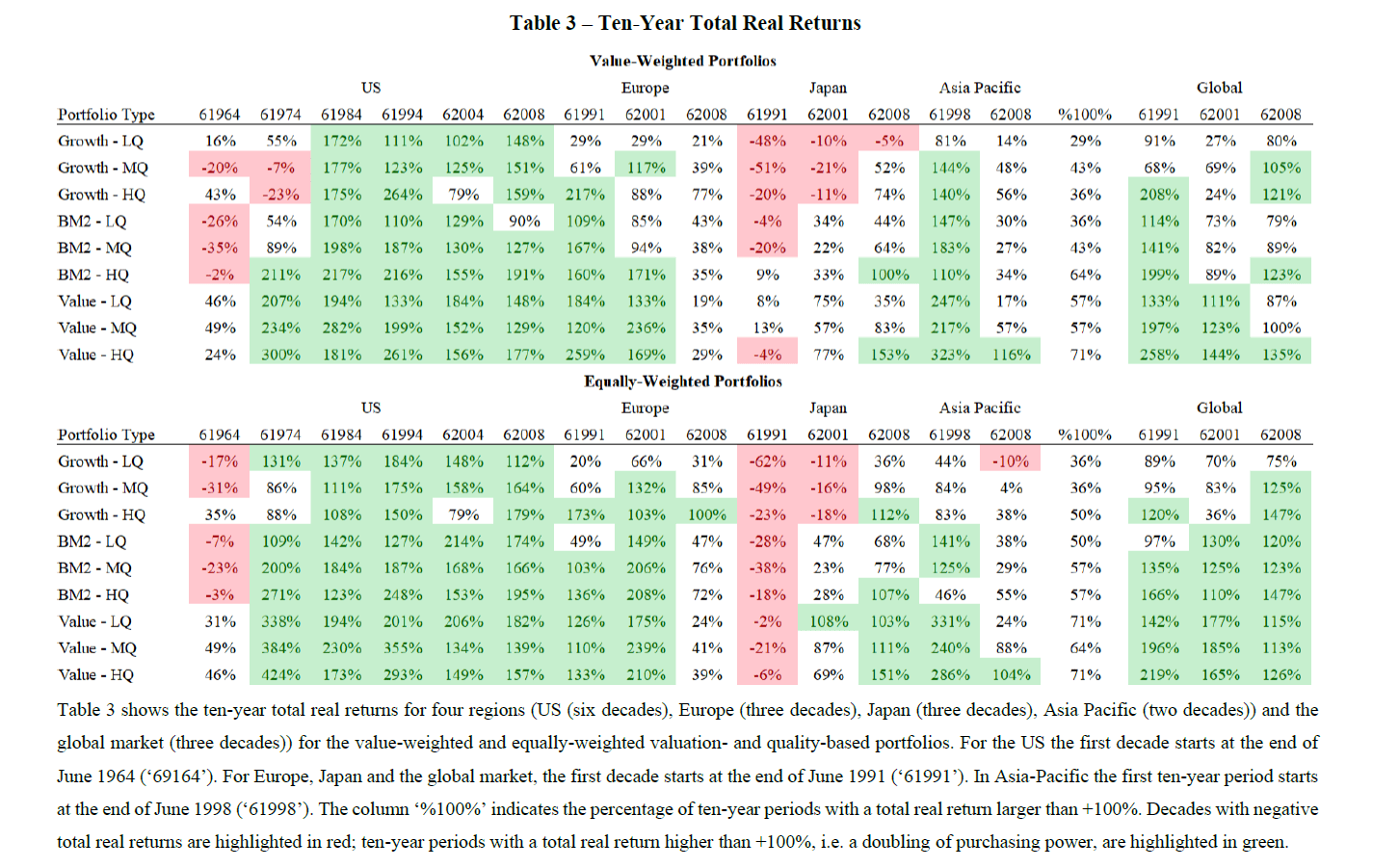

In this paper, in a first step, we subject the above technical insights to an empirical analysis in four regions (US, Europe, Japan and Asia Pacific) and the global equity market. We define a long-term capital loss as a real capital loss over a ten-year investment horizon. Valuation is measured by the market-to-book ratio (Lakonishok et al., 1994). Quality is assessed by a company’s solvency, liquidity and profitability. Solvency is captured by total equity to total assets. Liquidity is measured by cash and short-term investments to total assets. Operating income to total assets measures profitability. In this way we opted for the most basic measures of solvency, liquidity and profitability.3 Based on these definitions we form valuation- and quality-based portfolios. Subsequently the empirical analysis proceeds in three steps. In the first place we document the investment risk of the fundamentals-based portfolios, i.e. we document the largest real long-term capital losses or the smallest real long-term capital gains in each of the four regions and the global equity market. Here we find that the largest real long-term capital losses are concentrated in high valuation portfolios. High valuation, low quality investors have been confronted with real capital losses of up to -75% over a ten-year investment horizon.

For high valuation, high quality portfolios we document real capital losses of up to -62%. On the other hand investors with a focus on margin-of-safety companies, i.e. low valuation, medium/high quality companies, have been able to avoid economically significant losses in purchasing power over ten-year investment horizons. During those worst-case ten-year periods all fundamentals-based investors have experienced short-term losses of -50% and more. Secondly we document the increases in purchasing power for the valuation- and quality-based portfolios for non-overlapping decades. Low valuation, high quality investors have realized a doubling of purchasing power in 10 out of the 14 decades. For high valuation, low quality portfolios we document a doubling of purchasing power in only 4 out of the 14 decades. Apparently margin-of-safety investors have succeeded in combining low investment risk with high inflation-adjusted returns. In the third empirical step we move slightly beyond The Intelligent Investor and document the relative maximum outperformance of the portfolios over three-year investment horizons. Already in 1973 Graham criticized professional investors obsessed with short-term investment results. In the four regions, as could be expected, all valuation- and quality-based portfolios are periodically confronted with economically significant underperformance over three-year investment horizons, both between and within style portfolios. In a second step, after the empirical analyses and notably in Section 6, we elaborate on the psychological implications of our empirical findings for investors. These implications were set forth by Graham (1949), in particular in the chapters The Investor And Stock Market Fluctuations and The Pattern of Change in Stock Earnings and Stock Prices.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we discuss the sample description, variable measurement and the portfolio characteristics. Section 3 to Section 5 is all about the empirical analyses. An overview, conclusions and implications for investors can be found in Section 6.

Read the full article here by Steven Klerck, SSRN