“Hidden assets” in many cases are the source of considerable value creation. And, sometimes, the asset and its value are not so much hidden as simply viewed through a different lens. The following story will provide an example:

In the early 1970’s, Diamond International Inc. began a program of diversification ostensibly to attempt to break its dependency on consumer spending cycles. The company began its life in the 19th century and introduced the safety match to America in 1882. However, the Diamond of the latter part of the 70’s held little resemblance to its origins. The board and CEO of Diamond believed that the diversification program was sound and did little to question its efficacy. What they saw was a company, which as a member of the Fortune 500, was well established and solid which was the extent of their view even though profits had stalled and the share price had been stagnant for a significant period of time.

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

In 1979, Jimmy Goldsmith, the Anglo-French corporate raider began to build a position in Diamond International. Goldsmith’s view of the company was quite different from that of Diamond’s board and management. What Goldsmith saw was a company that was horribly managed and that was comprised of a hodge-podge of materially undervalued assets. And hidden the midst of this conglomeration was an asset that had been on the books since the late 19th century and was carried on the Diamond balance sheet at its original value of $27 million: 1.6 million acres of timberland.

After fighting a series of battles (amazing that boards and managements so often fight to remain mediocre), Goldsmith was finally able to acquire Diamond, paying a premium to Diamond’s shareholders. Once fully in his possession, he started taking the steps that would realize the full value, that he had perceived, of the Diamond assets. He quickly sold off the various operating companies with the 1.6 million acres of timberland the only asset of Diamond remaining in his possession. After completely retiring the substantial debt incurred to acquire all of the shares of Diamond, he had made a profit in excess of $500 Million.

Fortune magazine said that the Diamond transaction was one of the financial events of the 1980’s. It was also one of the most profitable during that decade of many successful deals. Predictable however, was the overwhelming criticism of Goldsmith as an “asset stripper” and other less than flattering monikers. Yet, nothing could have been further from the truth. Expanding the concept of maximizing asset values even further, it is clear from the following results of the operations that were sold that assets were not “stripped” but instead were liberated:

- Packaging operation was sold to one of Ireland’s leading entrepreneurs, Michael Smurfit and it went on thrive under his ownership

- Playing Cards company was sold to its management. It soon moved from a loss making operation to one that was profitable

- The Wesray investment group acquired the Can company. Sales were increased 40% and profits 50% in short order under Wesray’s ownership.

- The Egg Carton maker was sold to its management who eliminated 3 layers of bureaucracy and turned the company from a money loser into a profitable operation within one year.

- Pulp and Paper business was sold to one of the best managed companies in the U.S. at the time, James River Corp.

The shareholders of Diamond received a premium for their shares. Jimmy Goldsmith, after retiring all debt made over $500 Million and all of the operations sold quickly improved in performance and thus, value, now that they were liberated from the stifling bureaucracy of Diamond. Increased value and performance accrue on three different levels. This really begs the question as to why Diamond’s board and management did not see the hidden values that Sir James Goldsmith saw.

The Goldsmith/Diamond story is one of extremes in regard to hidden and undervalued assets. Yet it does provide a clear example of how shifting the perception of an asset or assets can shed light on significant value previously not seen or actualized. And, in that regard, I believe that there is a similar hidden/undervalued situation in an arena not typically even considered to be an asset: Public Company Boards.

To really zero in on the thesis that public company boards are undervalued assets we have to delve into the governance model as opposed to individual boards. The current public company governance model is far from conducive to realizing the full asset value of a board. It is the model itself that is the underlying inhibitor of the full performance and asset value realization. And while there is constant effort made to improve public company boards, no action is ever targeted toward actually deeply analyzing and radically changing the model.

In stark contrast to the public company governance model is the governance model implemented at the portfolio companies of the top private equity firms. Analysis by EY and others show that private equity firm portfolio companies, over longer periods of time, outperform their publicly traded peers (same industry, geography and size) in enterprise value creation, EBITDA growth and productivity growth and other key underlying measures of value creation. And, most importantly, a number of major consulting firms have attributed this outperformance of the portfolio companies of the top private equity firms primarily to their governance models.

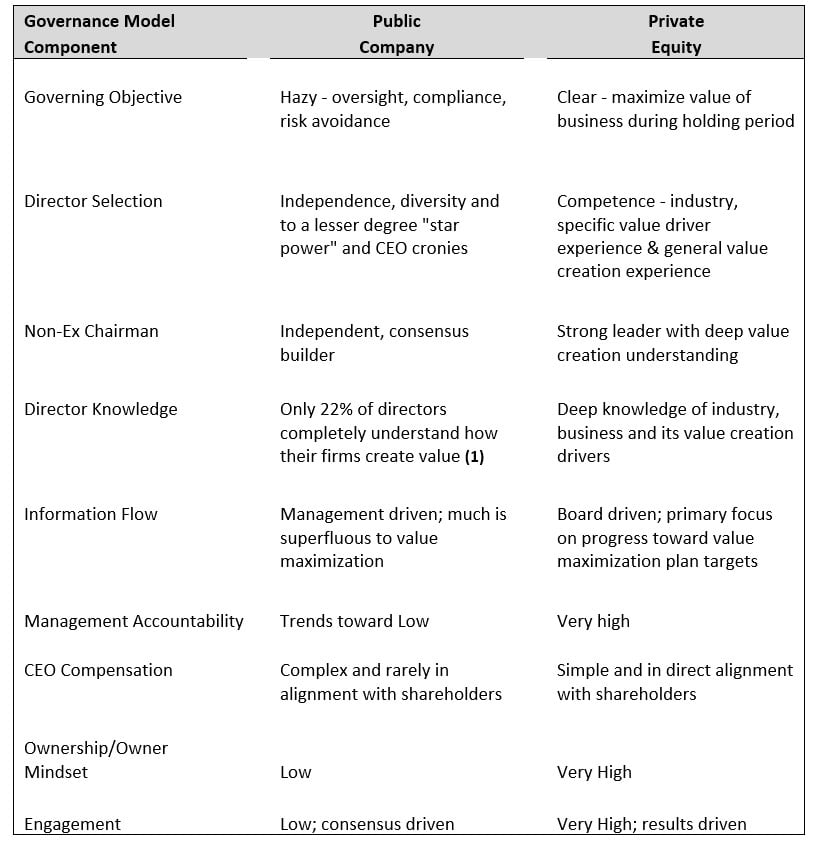

The following chart provides a high level look at the differences in the public company and private equity governance models:

From the above chart it is abundantly evident that in the context of performance and value creation, the private equity governance model is superior. In fact, a survey by McKinsey of chairmen and CEOs who had served on both public and private equity boards found: (2)

- Most said that PE boards were significantly more effective than those of public boards

- 15 of the 20 said that PE boards added more value; none said that the public counterparts were better

- On a 5 point scale (where 1 was poor and 5 was world class), PE boards averaged 4.6, public boards 3.5

- The intensity of the Performance Management Culture of PE boards was the single largest variance between the two types of boards

- Public boards focus much less on fundamental value creation levers and more on quarterly profit targets/market expectations

- Public boards seek to follow precedent and avoid conflict rather than exploring what could maximize value, i.e. more focused on risk avoidance than value creation

The operative thesis here is that the private equity governance model provides the light that can be shined on the public company governance model revealing its current state of underperformance yet at the same time the potential hidden asset value that exists. And, the key to the realization of this full asset value is to approximate the private equity model at public companies. Just as Jimmy Goldsmith radically altered the structure of what was initially an ossified Diamond International in order to liberate the full value of its assets, the bureaucratic public company governance model also needs to be radically altered for boards to reach their full potential and thus drive the development of the full potential and value of the company.

So, what does a radically altered public company governance model look like? As is discussed in detail in my book Governance Arbitrage: Blowing Up the Public Company Governance Model to Maximize Long Term Shareholder Value, the following are some of the components and characteristics of what I will call a Value Maximization Model for public companies:

- Have the clear governing objective of optimizing capital allocation and maximizing longer-term company performance and shareholder value

- Be led by a high performance non-executive chairman with responsibilities and qualifications distinct to this governance model including a deep understanding of value creation

- Be populated by directors with experience and track records that fall into one of three primary categories (track record cannot be overemphasized) 1. Company’s industry, 2. Specific experience related to one of the company’s mission critical value creation initiatives and 3. Broad value creation skills. It cannot be overemphasized how critical it is to have one or more directors with broad value creation and essential capital allocation track records similar to that of the senior personnel at the best private equity firms.

- Initiate an effective due diligence process that results in deep knowledge of the industry, the company and is levers for maximum longer-term value.

- With the knowledge gained from the diligence process, engage with management to set a longer-term equity value target and to identify the core initiatives that will drive the value to this target

- Remain aggressively and continually on the hunt for the optimum levers and initiatives to maximize the company’s potential

- Be intensely and aggressively engaged to ensure the governing objectives are met.

When what is typically considered to be assets are undervalued and the right change catalyst appears value can be maximized. The same concept and process is applicable to the public company boards – a shift to a value maximization model can, and likely will, create a governance arbitrage.