Most value investors have underperformed the last 5 years, and the reason why is simple. The ongoing bull market has interminably raged on past what most value investors would call prudent prices. In the current environment, caution has been penalized, not rewarded. Will record-high valuations go on indefinitely?

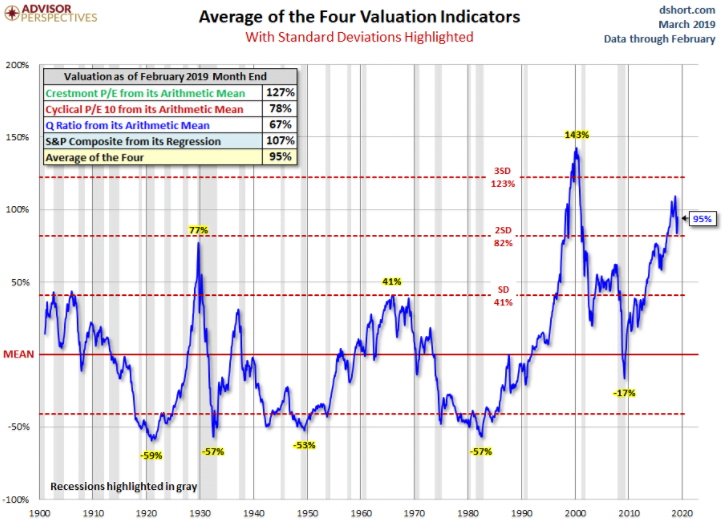

When we look at U.S. equity valuations, we are easily at the second-highest valuations of all time, and by some valuation metrics, the S&P 500 has eclipsed its all-time highest valuation in 2000.

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

The chart above is the average of four valuation metrics calculating valuations in different ways, which smooths out any deficiencies of any particular metric to give us a fair accounting.

Viewed in this light, U.S. equity markets have far to fall to get back to average valuations. Just reverting to the long-term average would imply roughly a 48% decline1. For a value investor, this is risky territory.

The potential return from the stock market comes down to a simple but powerful equation. The total return on stocks is: the change in valuation + growth in earnings + the dividend yield. Over a decade, earnings growth and dividends are relatively stable. The big unknown is the ending valuation (i.e., how optimistic or pessimistic investors are at the end of the decade), and that’s anybody’s guess. However, when valuations are lofty as they are today, nothing but extremely high valuations at the end of the next decade will deliver even decent (mid-single digits) returns.

The value investor’s argument is that these are appropriate prices at which to be defensive and possess far below average exposure to U.S. stocks. After all, one of the most famous instances of someone arguing for a “permanently high plateau” was Irving Fisher (a famous economist) in 1929—right before the Dow plunged almost 90%.

All logic suggests valuations are currently untenably high, but we can never be absolutely certain that valuations will revert to a historical average (until they do). As unlikely as it may be, what if valuations stay permanently high? Wouldn’t that be a good thing for a portfolio?

The Japanese Experience

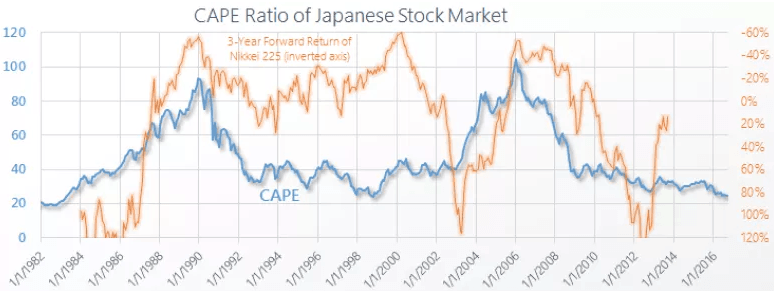

There is one famous instance in history where valuations reached an extreme peak and then managed to stay extremely high for a long time.

http://siblisresearch.com/data/japan-shiller-pe-cape/

Back in the late ‘80s, Japanese stock valuations, as shown by the blue line in the graph above, steadily increased to astronomical heights. The Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings (CAPE) ratio* reached a peak of roughly 90x earnings. To put this in perspective, the same valuation metric reached an all-time high in the United States during the tech bubble of a mere 44x earnings.2only did valuations reach never-before-seen heights in Japan, but they remained around a 40x-multiple for the better part of two decades.

The question is, with such high valuations for such a long time, how did investors fare? There is no doubt that some investors made hundreds of percent return in the run-up to the peak of the bubble. However, since the peak was reached in 1990, there’s been a lot of pain.

As we explore these numbers, please remember that the Nikkei never went below 20x earnings during this entire 30-year period. Most value investors would consider 20x earnings a pretty healthy (not cheap) valuation for a stock market. Note that the Nikkei returns were this awful even without a scenario in which valuations returned to “normal” prices. The numbers would be much worse if valuations had fallen to cheap valuations, like they have periodically in the U.S. markets.

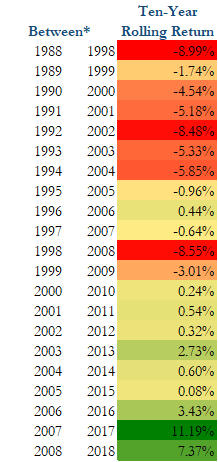

If you put a dollar in the Nikkei at the end of 1989, by the time you got to 2002, your dollar was worth 22 cents!3 This compounds out to losing more than 10% a year for a 14-year period. Now, you might think this is extreme, considering that the period starts at one of the highest valuations of all-time for any market. Fair point. Several respected firms, such as GMO and Research Affiliates, argue that starting valuations are informative about future returns 10 years out. So, let’s look at what 10-year rolling returns looked like in Japan during this perma-high-price period of 30 years.

Source: 3. Yahoo Finance

Looking at the numbers, if you’re a Japanese retiree with a “home bias” (i.e., preference to invest most equities in one’s home country), what you see is decimation. Most of these 10-year periods are negative, even though several of them started in years where valuations were cheaper than U.S. stocks are today. Only at the very end of this period did you have 10-year rollers with decent returns (the ones ending in 2017 and 2018.)

What does this mean for U.S. investors today? Does this mean U.S. equities can’t go higher? They still could. As Ben Graham said, “The short run is a voting machine, the long run is a weighing machine.” Said another way, where stock markets go over the short-term or even over a handful of years is primarily linked to psychology. If people feel more optimistic about the future than they did last year, markets go up, no matter the fundamentals. Historically, however, as Buffett has said, “sooner or later, valuations matter.”

Conclusion

If we “knew” valuations were going to stay high for a decade or two, similar to the Japanese experience, should investors ignore valuations and plow into U.S. stocks today? No. With ultra-high prices in the U.S. markets, the dividend yield on the S&P 500 is right at 2%, even though historically it’s been closer to 4.3%. Assuming no mean reversion at all, you’re losing about 2.3% in yield alone, bringing down historical returns from an average of 9% to around 6.7%.4

What the Japanese experience taught us is that you can have a major developed country (Japan was the world’s second-biggest economy in 1989) experience high valuations, have them stay high for a long-period (almost as long as most people’s retirement), and see dismal returns, despite the “permanently high plateau.”

Japan teaches us prices can stay high for a very long time yet that can coincide with decades of dismal returns. Those who are sanguine about the risk/return probabilities of U.S. stocks over the next decade are ignoring history and the mathematics of returns. Only an extremely optimistic scenario will generate returns that will satisfy equity holders. Virtually all the “value investing” legends have underperformed and not because they simultaneously got dumb. Instead, they have a discipline that demands prudence in this type of environment, and they understand, when faced with a bubble, you can look dumb before it pops—or after.

*CAPE is the current stock market price divided by the inflation adjusted average of the last 10 year’s earnings. It is meant to smooth out the business cycle to give a more stable representation of earnings.

Loic LeMener, CFA®, MBA, CFP® is a registered representative of Lincoln Financial Advisors Corp.

Securities and investment advisory services offered through Lincoln Financial Advisors Corp., a broker-dealer (member SIPC) and registered investment advisor. Insurance offered through Lincoln affiliates and other fine companies CRN-2484862-040119

Opus Wealth Management is not an affiliate of Lincoln Financial Advisors Corp.

Sources:

- Author’s calculation from Dshort chart above

- Robert Shiller – Irrationalexhuberance.com

- *I am using Yahoo Finance’s “adjusted close” numbers for the Nikkei index, which include dividends from December 31st of one year to December 31st of the following year.

- IBID Shiller

- Cape Ratio of Japanese Stock Market, http://siblisresearch.com/data/japan-shiller-pe-cape/

- Nikkei Return Calculator, with Dividend Reinvestment, https://dqydj.com/nikkei-return-calculator-dividend-reinvestment/

About the Author

Loic LeMener is founder and President of Opus Wealth Management in Dallas, Texas, a boutique wealth management firm that specializes in personalized client solutions. Loic and his team provide their clients with a targeted needs evaluation to answer important questions that provide a better, more personalized experience. The team focuses on integrity and believes in the following “golden rule” – they won’t do anything for you that they would not do for themselves or their loved ones.

Loic received his Masters in Business Administration from Southern Methodist University, studying Finance, Accounting and Portfolio Management. He also earned the CERTFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ certification and the prestigious Chartered Financial Analyst® designation. In addition, he has been quoted in national publications such as Barron’s.

In his free time, Loic is a devout reader, with his favorite topic being “value investing.” His favorite investors are Warren Buffett, Ben Graham, Charlie Munger, Seth Klarman, Howard Marks, and Jeremy Grantham.