A new scientific study from Friends of the Earth, with researchers at UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco, evaluating the impact of eating organic food on the pesticide levels found in the human body.

What Happens When We Eat Organic?

All of us are exposed to a cocktail of toxic synthetic pesticides linked to a range of health problems from our daily diets. Certified organic food is produced without these pesticides. But can eating organic really reduce levels of pesticides in our bodies?

In this peer-reviewed study, we compared pesticide levels in the bodies of four American families for six days on a non-organic diet and six days on a completely organic diet. We found that eating organic works.

An organic diet rapidly and dramatically reduced exposure to pesticides in just six days.

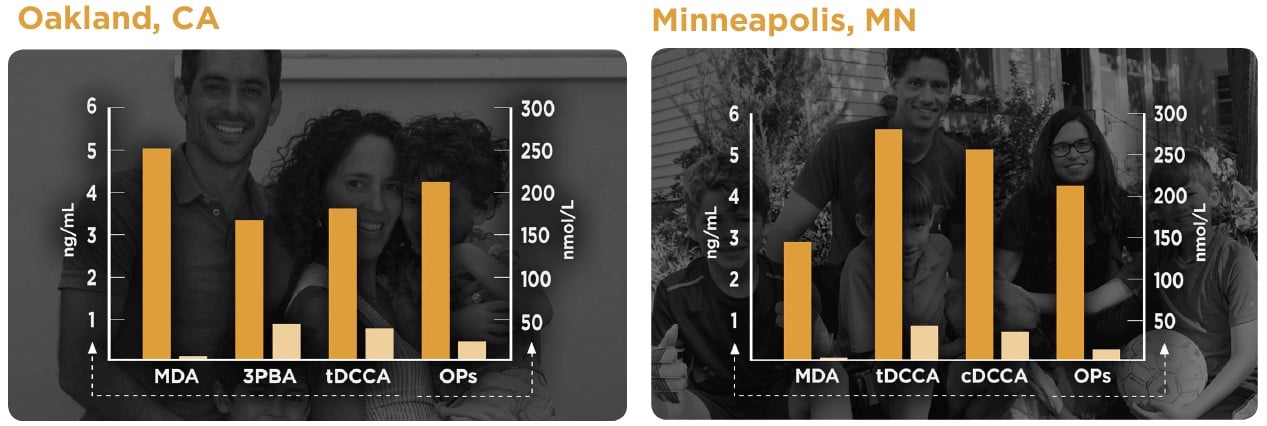

Top four pesticide decreases in each family

All detected pesticides dropped in each family, these charts show the top four decreases per family.

Organic Works

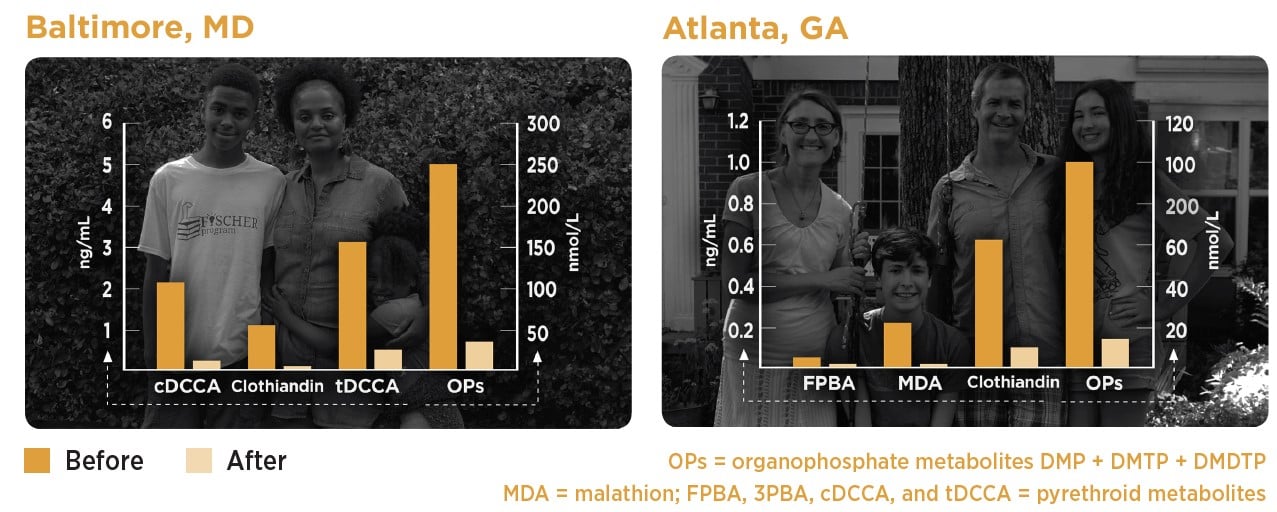

We found 14 chemicals representing potential exposure to 40 different pesticides in every study participant, including organophosphates, pyrethroids, the neonicotinoid clothianidin and the phenoxy herbicide 2,4-D.

Levels of all detected chemicals dropped an average of 60.5 percent in just six days on an organic diet with a range of 37 percent to 95 percent depending on the compound.

The most significant drops occurred in a class of nerve agent pesticides called organophosphates. The metabolites for malathion (MDA) and chlorpyrifos (TCPy) decreased 95 and 61 percent respectively, and a set of six metabolites representing organophosphates as a class (DAPs) dropped 70 percent. These pesticides are so harmful to children’s developing brains that scientists have called for a full ban. Chlorpyrifos is a neurotoxic pesticide linked to increased rates of autism, learning disabilities and reduced IQ in children and is also one of the pesticides most often linked to farmworker poisonings.

The neonicotinoid pesticide clothianidin dropped by 83 percent. Neonicotinoids are among the most commonly detected pesticide residues in baby foods.3 They are associated with endocrine disruption and changes in behavior and attention, including an association with autism spectrum disorder. Neonicotinoids are also a main driver of massive pollinator and insect losses, leading scientist to warn of a ‘second silent spring’.

Levels of pyrethroids were halved. Exposure to this class of pesticides is associated with endocrine disruption, adverse neurodevelopmental, immunological and reproductive effects, increased risk of Parkinson’s and sperm DNA damage.

Finally, 2,4-D dropped by 37 percent. 2,4-D is one of two ingredients in the Vietnam War defoliant Agent Orange. It is among the top five most commonly used pesticides in the U.S. and is associated with endocrine disruption, thyroid disorders, increased risk of Parkinson’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, developmental and reproductive toxicity and damage to the liver, immune system and semen quality.

Pesticide levels before and after switching to an organic diet

We All Have The Right To A Toxic-Free Food System

The science is clear. Organic agriculture can produce enough food to feed a growing world population while protecting our health and the environment.

We have the solution. And yet, our government subsidizes pesticide-intensive agriculture to the tune of billions of dollars while organic programs and research are woefully underfunded.

Pesticide companies spend tens of millions of dollars lobbying legislators and funding false science and front groups that mislead the public about the harms of pesticides to keep their toxic products on the market.

The top four pesticide manufacturers reap over $150 billion in profit each year. Meanwhile, the estimated environmental and health care costs of pesticide use in the U.S. is estimated to be upwards of $12 billion annually.

We should not have to “shop our way out” of exposures to toxic pesticides.

Elected officials must protect the health of people and the planet and stand up to corporate influence. And the food industry has a responsibility to consumers, the environment and society at large.

We all have the right to food that is free of toxic pesticides. The farmers and farmworkers who grow our nation’s food, and their communities, have a right to not be exposed day in and day out to chemicals linked to cancer, asthma, reproductive and developmental harm and other serious health problems. And the way we grow food should protect rather than harm the ecosystems that sustain all life.

Together, We Can Make Organic For All

Together, we can demand government and corporations step up to create a healthier world for all people. We can work together to pass laws in our cities, states and nationally that decrease pesticide use and expand organic farming. We can change the national Farm Bill — a major piece of legislation that determines how food is grown in the U.S. and what food is available to us as eaters. And, we can tell food companies and grocery stores to end the use of toxic pesticides in their supply chains and expand organic offerings.

The solution is here — we just have to grow it.

Organic diet intervention significantly reduces urinary pesticide levels in U.S. children and adults

Authors:

Carly Hyland1, Asa Bradman1, Roy Gerona2, Sharyle Patton3, Igor Zakharevich2, Robert B. Gunier1, Kendra Klein4

1Center for Environmental Research and Children’s Health (CERCH), School of Public Health, University of California at Berkeley

2Clinical Toxicology and Environmental Biomonitoring Laboratory, University of California at San Francisco

3Commonweal Institute, Bolinas, CA

4Friends of the Earth U.S.

Questions and Answers

Q: Can you briefly sum up your study?

A: We found that an organic diet rapidly and significantly reduced exposure to pesticides. We enrolled four families from across the United States and measured their exposure to a range of commonly used pesticides during six days on a conventional (non-organic) diet and six days on an organic diet. We found that urinary markers of exposure to pesticides dropped significantly — up to 95% — after only six days on an organic diet.

Q: What pesticides did you measure?

A: We found 14 pesticides and pesticide breakdown products (metabolites) in every participant that represent exposure to organophosphates (including chlorpyrifos and malathion), pyrethroids, neonicotinoids, and the herbicide 2,4-D.

Q: What were the main findings?

A: After the organic diet intervention, pesticide levels dropped on average by 60.5%, with a range of 37% to 95%, depending on the compound. The most significant decreases occurred in a class of neurotoxic pesticides called organophosphates. Organophosphates are so toxic to children’s developing brains that some scientists have called for a full ban. 1 This class includes chlorpyrifos, a pesticide linked to increased rates of autism, learning disabilities, and reduced IQ.2,3 The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency abandoned plans to ban chlorpyrifos in 2017, defying the agency’s own scientists.4 In August 2018, a federal court ordered the EPA to ban chlorpyrifos.5 Our study found a 61% reduction in chlorpyrifos, 95% reduction in malathion (a probable human carcinogen), and 70% reduction in DAPs metabolites that represent overall organophosphate exposure. We also found that the neonicotinoid pesticide clothianidin dropped by 83%. Levels of pyrethroids were halved, and 2,4-D dropped by 37%.

Q: Who participated in the study?

A: We enrolled families with one to three children from Oakland, CA, Minneapolis, MN, Atlanta, GA, and Baltimore, MA that typically ate a conventional (nonorganic) diet.

Q: Have there been previous studies like this one?

A: Yes. There have been three diet intervention studies that have provided consistent evidence that switching to an organic diet can significantly reduce pesticide exposure among people who typically eat conventional food. Two of the previous studies, in California and Washington, researched children. The other was a pilot study of two adults in Switzerland.

Q: What is new about your study?

A: Previous studies focused on exposure to classes of insecticides known as organophosphates (OPs) and pyrethroids. Our study addresses an important data gap around exposure to neonicotinoids and the potential of an organic diet to reduce these exposures. Neonicotinoids are now the most widely used insecticides in the world and are among the most commonly detected pesticide residues in baby foods. They are taken up into the tissue 6 of plants, so the residues cannot be washed off of food. Neonicotinoids are associated with endocrine disruption and changes in behavior and attention, including an association with autism spectrum disorder.7,8,9 Neonicotinoids are also a main driver of massive pollinator and insect losses, leading scientist to warn of a ‘second silent spring’. 10,11 In our study, levels of the neonicotinoid pesticide clothianidin dropped by 83%.

This was also the first organic diet intervention study to monitor the impact of an organic diet among both children and adults. Given their different metabolisms and dietary patterns, this provides a useful comparison. We also had greater rigor in the control of our diet intervention than other studies — we had research assistants shop for the families and certified chefs prepare dinners during the organic phase to guarantee 100% organic down to oils, spices, beverages, etc. Previous studies only substituted some categories of food such as fruits, breads, cereals, vegetables, dairy, eggs, juices, and snack foods.

Q: Why should these findings be of interest to the public?

A: Diet is one of the primary sources of exposure to pesticides for the general public. This study shows that eating an organic diet can help avoid and reduce exposure to a range of pesticides.

Q: You show that families can reduce their pesticide exposures, but what

about their health?

A: Our study does not assess health outcomes. The scientific literature shows that exposure to pesticides is associated with a range of health problems, including cancers, IQ deficits and ADHD-type behaviors in children, hormone disruption, reproductive and fertility problems, and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. While most of the studies that have examined the health effects of pesticide exposure have taken place in agricultural settings among farmworkers and their families — who have higher levels of pesticide exposure than the general public — a growing body of research shows that longterm exposures to even small levels of pesticides (in parts-per billion) are harmful.

While more information is needed about the health effects of chronic, low-level exposure to pesticides in our diets, a recent study that followed nearly 70,000 adults in France over seven years found that an organic diet was associated with a lower risk of cancer. Another 12 recent study found fertility benefits for women who more frequently consumed organic food.13

Q: Did the participants give you permission to use their names and photos?

A: Yes. First we shared individual results with the families. Agencies including the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences are encouraging the sharing of research results with study participants and their communities. After providing individual results, we received consent from the families to share aggregated results publicly.

Q: Who funded the study?

A: The project is possible thanks to the generous members of Friends of the Earth U.S. This work is also supported by grants from foundations, including California Consumer Protection Foundation. Friends of the Earth received no funding from organic food companies or trade associations to produce this study. You can read our organizational policy on funding here.

Q: Are there limitations to your study?

A: While the study included only 16 participants, we collected urine samples from every participant over 12 consecutive days, resulting in 158 samples for analysis, which is a robust sample size.

Our study assessed dietary exposure to pesticides, however, people are exposed to pesticides that are used in homes, buildings, yards, and parks. While we confirmed that participants did not use pesticides in their homes during or prior to our study, since people aren’t typically notified about pesticide spraying in schools, offices, and apartments, the participants were not able to identify if they had been exposed to pesticides outside of their home. We assessed exposure to a class of pesticides called pyrethroids. These are some of the more commonly used pesticides for pest control in homes and buildings. The striking decrease in pyrethroid exposure we observed in our study indicates that diet was the primary exposure among participants.

Q: Did you test for pesticides used in organic agriculture?

A: Laboratory methods did not allow measurement of spinosad, the single naturally-derived pesticide approved for organic production with a U.S. EPA food tolerance. Spinosad has low toxicity. All other pest control agents allowed in organic production are “tolerance exempt” meaning that the EPA has evaluated the scientific data related to human health and has determined that they are not harmful.

Q: What are some of the next steps?

A: There has been consistent evidence from organic diet intervention studies that consuming an organic diet can reduce pesticide exposure, however purchasing organic food and beverages is not an option for all families as organic can cost more than non-organic.

This research supports Friends of the Earth’s Organic for All campaign that advocates for a food system where organic is available to all (see www.OrganicforAll.org) Currently, farming with toxic pesticides is the norm and the federal government subsidizes pesticide-intensive agriculture at a cost of billions of dollars annually. At the same time, organic research and programs that help farmers transition to organic and learn to implement organic practices are woefully underfunded. A redirection of public dollars would help the organic sector grow and could help ensure that more people could access organic food. Friends of the Earth believes that all people have the right to food that is free of toxic pesticides, that the farmers and farmworkers who grow our nation’s food, and their communities, have a right to not be exposed to pesticides linked to serious health problems, and that the way we grow food should protect rather than harm the ecosystems that sustain all life.

We are working with farmer, farmworker, environmental and consumer organizations across the country to create a food system where organic is for all. We work to pass laws in our cities, states and nationally that decrease pesticide use and expand organic farming. We are also working to change the national Farm Bill — a major piece of legislation that determines how food is grown in the U.S. and what food is available to us as eaters. And, we are leading a campaign urging the top 25 food retailers in the U.S. to end the use of toxic pesticides in their supply chains and expand organic offerings, prioritizing domestic producers.