Broyhill Asset Management annual letter for the year ended December 31, 2018.

For the year ending December 31, 2018, Broyhill generated low single-digit losses with significantly less volatility than global equity markets. While it’s painful to watch gains on the year vanish in the final month, we are pleased to report that January’s mid-single digit gains have already offset last year’s minor decline. Detailed quarterly reports, including account and benchmark performance, portfolio holdings, and transaction history, have been posted to our investor portal.

Q4 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.” - Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale Of Two Markets

What a difference a year makes. In contrast to the subdued volatility in 2017, last year certainly tested that old cliché “it’s a bull market somewhere.” Markets kicked off the year where they left off: after ten years of economic expansion and one of the longest uninterrupted bull markets in history, investors were feeling warm and fuzzy. But this widespread optimism reversed course alongside share prices in October. Complacency was replaced by panic in a matter of weeks.

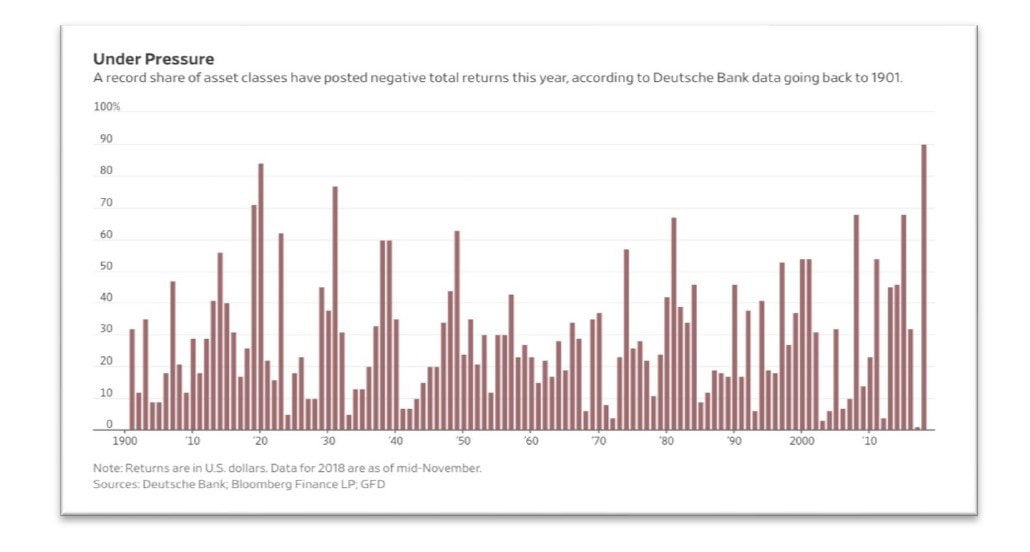

December felt like an eternity for wrong-footed investors and not because of their child-like anticipation of Santa. By the time it was over, no asset class gained more than 5% on the year, for the first time in decades. Volatility reached the highest level since 2009, and December’s 9.2% drop in stocks was the second-worst since 1931. Stocks, bonds, and commodities staged a simultaneous retreat, one of their worst years on record. In short, it was a sea of red. US cash turned out to be the best option for the year, while most asset classes were crushed. In fact, 90% of asset classes posted negative returns, unparalleled in over a century of data.

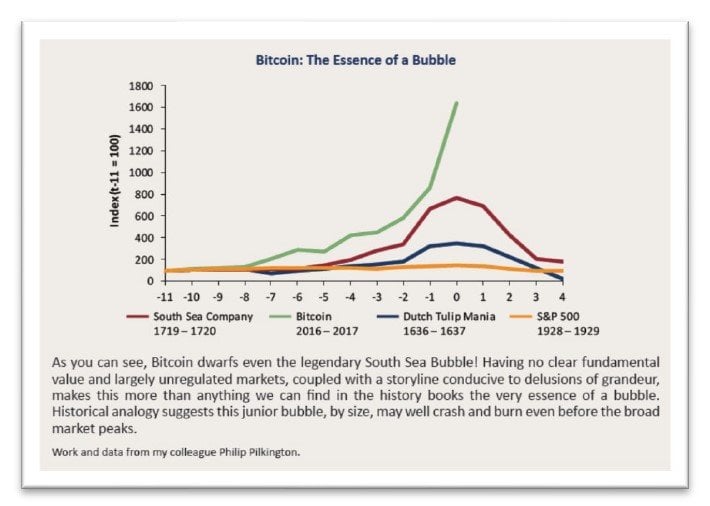

While the year began with dreams of synchronized global growth, it concluded with nightmares of a synchronized global slowdown. For now, the US appears to have decoupled from the rest of the world, but history suggests that decoupling is just another urban legend, like Sewer Alligators, Doppelgangers, or the Intrinsic Value of Bitcoin.

Against this backdrop, we held our own and protected capital in a brutal market; in other words, we did what our clients hire us to do. During the last six months of the year, we added to several positions that became cheaper and moved into a handful of new investments, but in no way did the brief decline push us all in. While 2019 is off to one of the best starts in years, the underlying risks that led to such a devasting year-end are still largely in place. As such, we continue to think markets are coming our way, and we are as excited as we’ve ever been about the portfolio and the opportunities ahead.

Great Times Are Great Softeners

The Fed is back in the limelight. While a pause in tightening may have put a temporary floor under equity markets, we believe risk assets are again vulnerable to disappointment after such an extended move off the lows. Additional evidence of an economic slowdown, negative earnings revisions—or any trade deal viewed inferior to “the best ever” —might well result in the typical “buy the rumor, sell the news” situation. Better to reduce risk now than wait for everyone else to do so when the exits are much more crowded.

As many investors were reminded last year, rising prices have a way of lulling us into complacency. Every purchase is a good one. Every sale, a mistake. Each tick higher provides us with additional confirmation bias. Why question our assumptions when the market agrees with us? Why challenge our initial hypothesis when it has been validated by our growing brokerage statements? When times are good, safety nets go unused on the sidelines. Investors grow lazy, overconfident, and unprepared.

The fourth quarter was a wakeup call for many who were caught offsides after years of uninterrupted growth and rising prices. It was a reminder that bad investors are destroyed by crises, good investors survive them, and great investors are improved by them. As Benjamin Franklin wrote, “The things which hurt, instruct.”

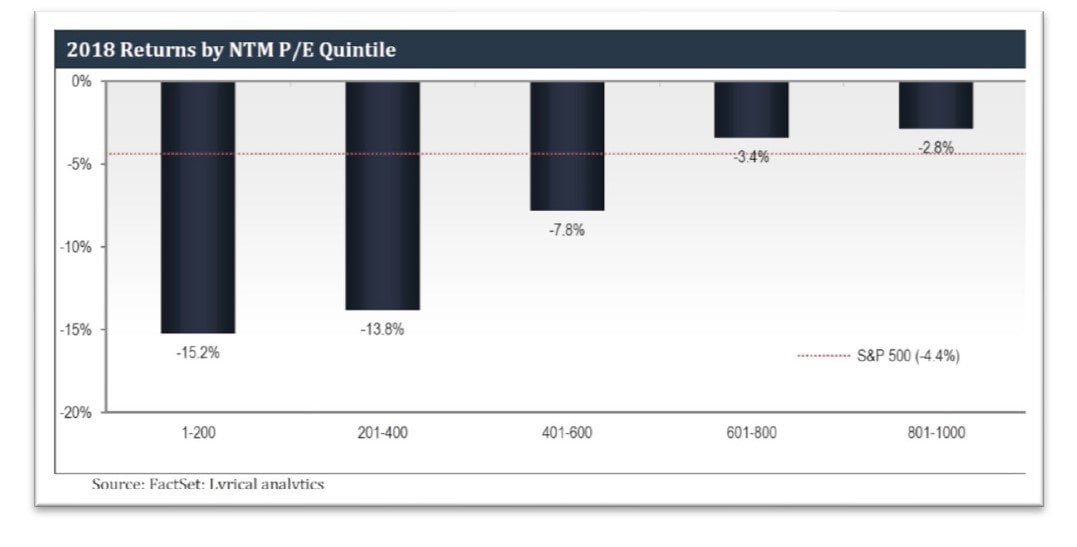

Good bargains often become great bargains in bear markets. And last year was a particularly tough one for good bargains. As shown in the chart below, the cheapest quintile of the S&P was down more than 15% for the year, underperforming the index by more than 10% in 2018.

Measured with this yardstick, last year was the worst year for value investing since the bursting of the internet bubble two decades ago.

The good news is that value stocks went on a magnificent run the following decade, outperforming both passive indices and momentum investors for over ten years. We think the conditions are now in place for a similar run. To understand why, let’s take a step back to compare the set ups now and then.

Back To The Future

It’s easy to fall in love with your winners, to stick with what’s working. It’s much harder to deviate from the consensus and stand apart from the crowd. That’s why investors rarely sell what’s working, no matter how expensive it’s become. They hold onto winners for too long simply because those winners have done well. It’s much easier to sell what’s in the headlines, what isn’t working, and what’s disappointed, no matter how cheap it’s become.

When they’re flush with capital inflows, neither passive nor active managers buy the laggards since, by definition, those are the investments that haven’t worked. Instead, they buy more of what’s working, further reinforcing the feedback loop. This is a dangerous state of affairs.

When stocks are rising simply because they have risen, it gets difficult to imagine them doing anything else. It’s even more difficult to imagine why you would ever sell an investment with such a great track record and an obviously bright future.

When fundamentals are this strong, why shouldn’t prices be this high?

With the market constantly confirming our thesis in the form of rising prices, why would we ever sell our winners to diversify into weaker companies?

Why should we ever sell US equities, when the US economy is in far better shape than anywhere else in the world?

This is the mindset that caused one of the greatest bubbles of all time exactly two decades ago. And perhaps it is this mindset, once again, that is driving asset prices to extremes.

Bubbles form when things are good and when it’s difficult to imagine anything but things being good. Take, for example, improving fundamentals in the US economy on the back of accelerating growth, a pro-business administration, corporate tax cuts, and surging corporate profits. Put them together, and you have a marvelous recipe for growing optimism. But sentiment can’t grow more optimistic forever.

Bubbles burst when changes in sentiment turn negative. This can be difficult to appreciate since fundamentals usually look and feel quite good when optimism begins to slow. This is why many investors were at a loss to make sense of price moves during the fourth quarter. The US economy was still chugging along. But things were just not quite as good as before. And a small change in optimism, when there is nothing left in the tank to fuel rising prices, can shift sentiment ever so slightly, which in turn can let the air out of the bubble.

They say that gradually letting the air out of a bubble is like trying to gradually let a fart out at a cocktail party. It’s a risky move with a blemished track record—for party-goers and for the Fed. As a result, like those uncomfortable moments at the cocktail bar, bubbles have a tendency to linger longer than anyone expected and surprise everyone by how magnificently they burst.

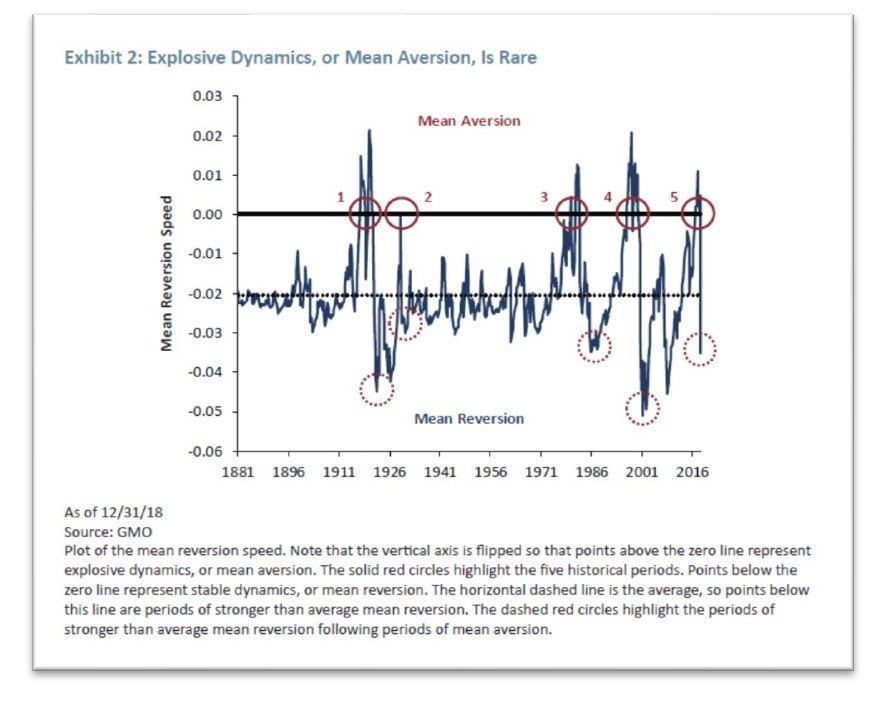

Research from GMO, who has perhaps the best track record at cocktail parties, supports this casual thesis.

When a bubble bursts, mean reversion comes back with a vengeance. When valuation is extreme, relatively small changes in sentiment are amplified by the extended valuation and can produce large changes in price.

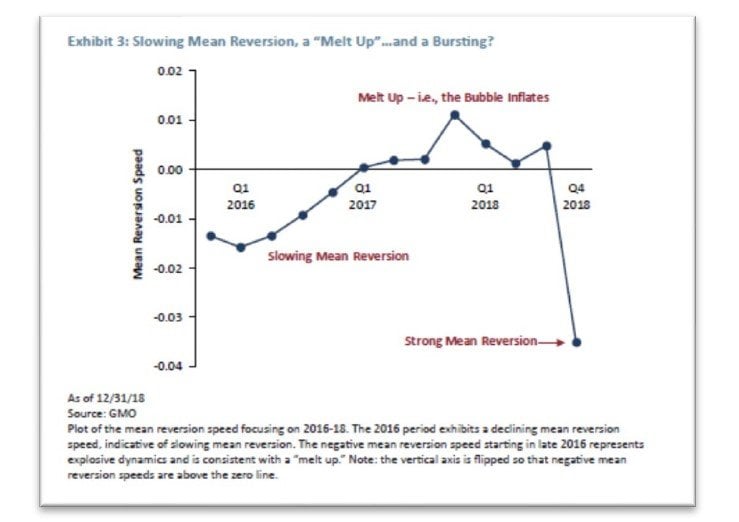

Prior to the fourth quarter of 2018, the most extreme change in the mean reversion speed is the one from the third to the fourth quarters of 1929 . . . However, the change in the mean reversion speed from the third to the fourth quarters of 2018 eclipses that of 1929, highlighting just how dramatic the last few months have been. The magnitude of this move also tilts the odds in favor of the view that we may currently be experiencing the initial stages of the bursting of the bubble of 2017-18.

Why is this important?

Because the scale and duration of mean reversion evidenced in the fourth quarter of last year is consistent with the bursting of previous bubbles, most notably the 1929 and 1999 bubbles.

This framework helps us understand that, even though earnings grew a healthy 28% in 2018, the downshift in expectations for 2019—combined with increasing uncertainty—may well be the catalysts that pop this bubble. As shown below, the data point for Q4-18 implies an explosive change in the speed of mean reversion, not unlike that uncomfortable explosion at that cocktail party.

Near the market’s top last summer, the median price-to-earnings multiple for stocks listed on the NYSE had reached record extremes, exceeding the bubble peaks in 1929, 2000, and 2007. At the same time, the price-to-sales ratio for S&P 500 stocks exceeded the all-time 2000 high. And the median-price-to-sales ratio was two times greater than the top in 2000. Let that sink in for a moment.

If markets were to revert to fair value, as all previous bubbles ultimately have done, the fourth quarter sell off just scratched the surface. This is hard to imagine, so most investors just ignore the possibility. Instead, they argue that, as the most hated bull market in history, this ten-year rally lacks the typical anecdotes that accompany historical bubbles. We would disagree and point to extreme enthusiasm around Machine Learning, Big Data, Artificial Intelligence, Bitcoin and just about any subscription-based business model.

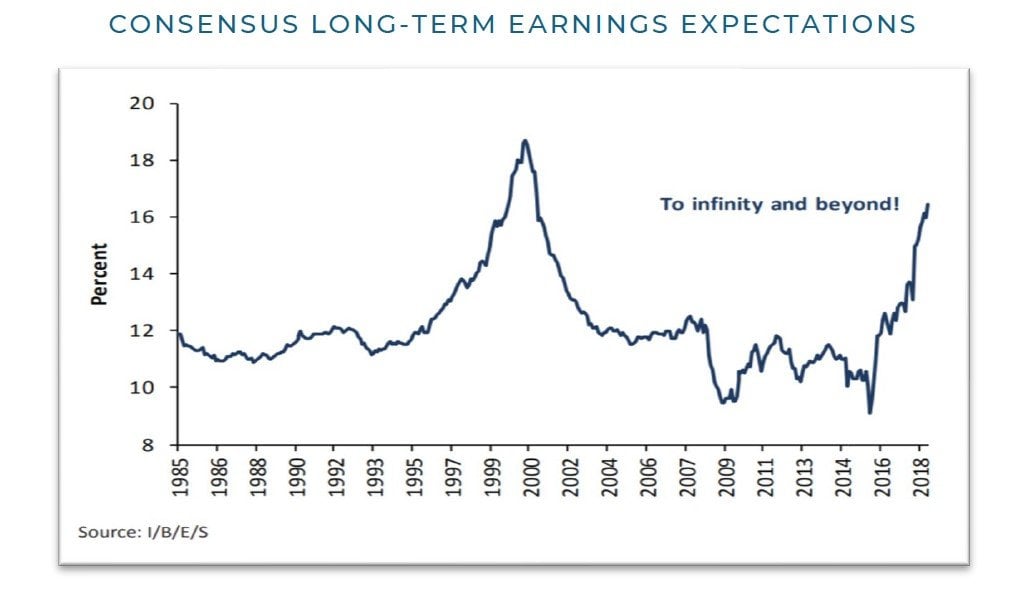

Perhaps the most disturbing evidence of blissful optimism is the chart below, which shows consensus long-term earnings expectations. For perspective, consider that since the last economic peak in 2007, GAAP earnings have grown at 3.8% annually, and since the 2000 economic peak, GAAP earnings have grown at 5.1% annually, which is a tad closer to the historical average.

Expectations today have soared to levels last seen during the tech bubble of the late 1990s. Clearly, analysts are once again unusually enthusiastic about growth prospects.

A Measured Approach

Prudent investors would be well served to recall that financial imbalances, which can appear to go on forever, often reverse course suddenly and with little warning. With corporate leverage at historic extremes and credit quality deteriorating, the risk of a financial accident has greatly increased. Domestic equity markets are trading near peak multiples on peak margins, and consumer confidence and household equity allocations are at record highs. At the same time, downward revisions to top-line guidance—combined with rising input costs, higher wages, and rising debt burdens—are likely to squeeze profit margins.

The US is still bearing the brunt of last year’s tightening financial conditions. And political paralysis, as evidenced by “the best government shutdown” ever, could also weigh on domestic growth. While the future is, by definition, always uncertain, “this future” seems more uncertain than ever. Dysfunction in Washington has already resulted in a spike in the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index, which is historically detrimental to capital investment, harmful to economic growth, and inversely correlated with global equity performance.

Investors have responded favorably to the Fed’s pause, providing an immediate and drastic boost to equity markets, but it’s important to remember that pauses happen for a reason. The Fed is reacting to weaker economic data, reflected in earnings and stock prices. And while monetary policy at home may be on hold for the moment, global monetary policy has become much less accommodative. Pauses, are more often than not, prelude to recession.

Whenever more than half of the world’s central banks have tightened their monetary policies, stocks have underperformed. And today, nearly two-thirds of the world’s central banks are doing just that. While US growth remains strong, it is not immune to the slowdown. In fact, in previous global slowdowns, the US often followed suit, entering a recession about six months later. While the distinction between slowing growth and a recession may seem arbitrary, the outcome for equity markets is significant.

Large drawdowns in global equities have always occurred in or around OECD-defined global slowdowns, and the most severe bear markets have been accompanied by a US recession. Common sense suggests that if low rates and loose monetary policy can drive asset prices higher, then increasing rates and tightening monetary policy should have the opposite effect.

The Art Of Investing

Horace wrote Ars Poetica in 19 BC to offer advice on the art of writing poetry. Since then, it has inspired poets and authors, and it’s been used in literary criticism since the Renaissance. It has also inspired value investors since it was cited in Benjamin Graham’s Security Analysis, which advises on the art of value investing, published near the trough of the Great Depression in 1934.

Successful investing requires the confidence to trust your work, even when market prices are screaming that you are wrong. Yet, successful investors are still human. At Broyhill, we are not robots. We still feel the turning in our stomach when prices are plummeting. But rather than succumb to the market, we reflect when positions move against us, balancing confidence and humility. Staying power is greater than intelligence.

Investing is all about expectations. It’s not enough to understand that a company’s competitive position is unparalleled. Or that its fundamentals are deteriorating. To generate excess returns, you must also have a view as to why future fundamentals will be different than expected. If they are not, even a company with terrific fundamentals can be a poor performer. Conversely, a company with terrible fundamentals can be a great stock. Stocks do poorly when they disappoint. The flip side, of course, is that they do quite well when they surprise to the upside.

If everyone already knows that fundamentals are weak, there’s no sense in selling. We focus on those situations in which expectations are so low that the odds of a positive surprise are in our favor. In other words, we focus on the fallen that are likely to be restored.

Low expectations don’t guarantee good outcomes. But when the bar is set low enough, positive surprises are much easier to come by. That seems a lot easier than depending on perfect execution to get more perfect. To do this, one must remain comfortable holding the view that the market is wrong, that price is a liar.

Why might markets be wrong? Perhaps those selling stock are not thinking clearly at the moment. Perhaps they are overleveraged or overexposed. Perhaps they are selling for other not rational or economic reasons. We don’t always know.

We can only do our best to assess the gap between today’s price and what we think the business is worth. We buy when that gap becomes too wide.

If you obsess over falling prices, you’ll miss the opportunity to buy more. Or, worse, you’ll panic and puke up your best positions as they plummet. In the final months of last year, we saw a lot of panic and a lot of forced liquidation. In contrast, we sat tight and put our trust in the process. We put trust in our research that has identified strong potential among the fallen. Suffice it to say, we think the bar is set sufficiently low for our portfolio companies to clear.

Dragnet And Our Top Five

In the final quarter of the year, the most common questions we heard were along the lines of: “How are you guys holding up? What are you doing with the portfolio here?” The short answer: okay and nothing.1 Whatever we “were doing with the portfolio” we did earlier in the year. You need to buy insurance before danger strikes. Once your house is on fire, it’s too late.

We spent the first three quarters of the year repositioning the portfolio into out-of-favor, non-cyclical businesses that were trading near trough valuations but were capable of compounding earnings through a downturn. So, while most managers were busy selling off their leveraged longs, we held onto companies that were posting solid and stable cash flow throughout the year. Below is a brief update on our top five holdings, which represent roughly half of our equity exposure today.

Dollar Tree Stores (DLTR)

Dollar stores have historically provided both consumers and investors with tremendous value. Over the past decade, shares of DLTR have compounded at 20% annually, although the stock had a rough slide last year, dropping more than 15%. This provided us with an opportunity to increase our position.

We believe that consensus is overly focused on the Family Dollar business, which DLTR acquired in 2015. While Dollar General (DG) provided DLTR with a proven playbook for fixing Family Dollar, progress to date has been choppy. Long-term investors in DLTR are rightly frustrated, but we believe patience will ultimately be rewarded. In the meantime, the Dollar Tree segment, which represents more than three-quarters of operating profit, is performing well in a challenging retail environment: same-store sales growth has exceeded 4% over the trailing twelve months. We believe downside risk is limited and that management, or perhaps other interested parties, have plenty of options at their disposal since the market currently assigns little value to the FDO segment, which was acquired for $9 billion just a few years ago.

Oaktree Capital Group (OAK)

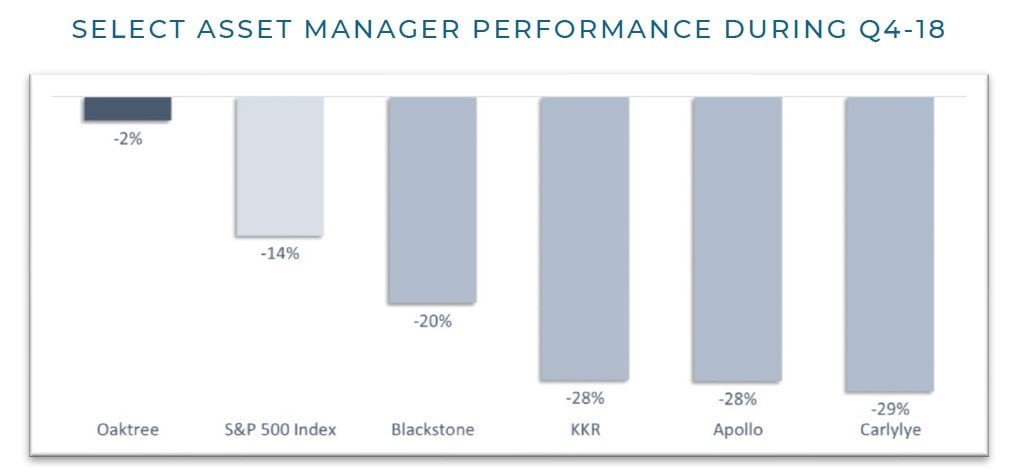

Oaktree is a world class investment firm, founded in 1995, with deep expertise in credit. OAK’s core values, which inform every investment decision, are grounded in antifragility. Ironically, this is also the reason for the stock’s underperformance in recent years.

Since OAK invests the majority of its capital during periods of distress and focuses on the most senior securities in the capital structure, the long and uninterrupted bull market has resulted in few low-risk opportunities to put money to work. Yet investors who wait for a bear market before investing in OAK risk missing out on the benefits of the stock’s countercyclical business model. We got a glimpse of how the market may rank OAK’s peer group when the cycle turns during the fourth quarter of last year (see chart below).

Oaktree should gain tremendously from increased disruptions in the capital markets. As one of the best distressed investors in history, Oaktree’s business improves when external shocks, failures, and volatility are on the rise. Oaktree is one of the highest quality businesses in our portfolio, managed by a team that collectively owns most of the stock. The shares change hands today at less than 10x our estimate of normalized fee-based earnings, net of the asset value carried on the books, which make up roughly half of OAKs current market capitalization.

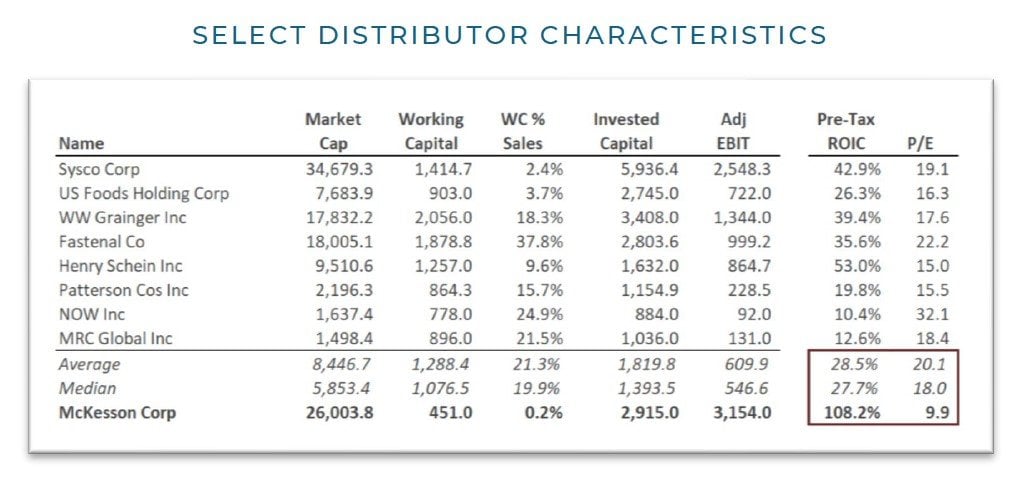

McKesson Corporation (MCK)

We first discussed our investment in McKesson in our mid-year letter to investors. The stock continued to decline (almost without fail) into year end. Whenever this happens, we naturally wonder what we are missing. With the stock trading at single-digit multiples, the risk of overpaying for the business appeared minimal. But, of course, we needed to understand why it was cheap. In our view, MCK was down for three reasons:

I. Industry concerns around drug pricing and the political environment;

II. Uncertainty regarding Amazon’s entry into the healthcare supply chain; and

III. Potential liability from the opioid epidemic. So, the question then becomes, can we identify a catalyst to change investor perception? The short answer is yes.

With Democrats winning the House, gridlock should create a more stable political environment for healthcare. Meanwhile, continued earnings growth and free cash flow generation should ultimately convince investors that the sky is not falling, and as a result, multiples should improve. And any settlement for less than the eye-popping headline risk of $100 billion should quell investors’ worst fears about the company’s opioid liability.

Despite the ongoing headline risks, we believe that pharmaceutical distributors are among the most attractive, high-quality distribution businesses one can own. While drug prices may fluctuate in the short term, the long-term outlook for prescription drug growth will almost certainly increase the number of scripts sold in the US.

McKesson benefits from high barriers to entry in the form of regulatory hurdles, rational competition between the top three distributors (who account for 90% market share), and demand growth that shows little sensitivity to economic conditions. Yet, investors are valuing the stock at a significant discount to the group, despite returns on capital far above the profits generated by other distributors.

Walgreens Boots Alliance (WBA)

Walgreens is one of the largest retail pharmacies in the world and operates in a relative oligopoly in the US. Despite its strong market share in the healthcare supply chain, the stock has been under pressure given the increasing pricing power of its suppliers and Amazon’s entry into the online pharmacy business. At year-end 2018, WBA traded at a discount to its year-end 2008 multiple. With a number of levers to pull—Rite Aid integration, procurement, cost savings and store optimization— positive surprises should be easy to come by. Shares would also benefit from a shift in sentiment that pushes investors toward value-oriented names with little exposure to a slowing economy.

Allergan (AGN)

Allergan, a pharmaceuticals company best-known as the manufacturer of Botox, has seen its share price cut in half over the past few years—from a July 2015 peak of $340 to a recent low of less than $150. Even though the company’s cash flow generation and earnings power have remained steady, the multiple on the stock has plummeted from a high above 20x earnings to a record low below 10x earnings. When we began buying shares, we identified multiple ways to win. However, it wasn’t clear how we’d get there or when we’d arrive. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. The catalyst is not always obvious in advance. If you buy right, it usually doesn’t matter. Ultimately, the value you uncover will be realized by the market—or by someone else—in some form or fashion. With respect to our investment in AGN, we recently reviewed potential catalysts to higher valuations in a write-up, available here.

Bottom Line

Broad market indices remain very expensive, and we are very late into a very long economic cycle. With valuations quickly back at all-time highs despite the clear slowdown in economic growth and corporate profits, the risk-reward appears greatly skewed to the downside. But the risk of getting too cautious here is also manageable, in our opinion.

We are finding more and more pockets of value today. Many of the companies in our portfolio are absolute bargains that are trading near multi-year lows. We own a concentrated portfolio of great businesses at great prices. As of year-end, many were trading at single-digit earnings multiples, despite the likelihood of continued earnings and cash flow growth well into the future. We remain very excited about the prospects for our portfolio, despite our lack of enthusiasm for the market. As they say, it is a market of stocks, rather than a stock market.

Our office was quiet during the fourth quarter carnage.

Our phones did not ring any more than they typically do.

Our long-term orientation allows us to look out further on the horizon to capture investment returns that are just not available to those focused on the next data point or the next quarter. Do not underestimate the impact that your trust and support have on our own confidence and our ability to make sound decisions on your behalf. A day doesn’t go by that we are not thankful for it.

We put one foot in front of the other each day, recognizing that excellence is achieved one step at a time. Nick Saban, the head coach of Alabama—perhaps the most dominant dynasty in the history of college football—credits two words for his team's unprecedented success: the process.

Don’t think about winning the SEC Championship. Don’t think about the national championship. Think about what you needed to do in this drill, on this play, in this moment. That’s the process: Let’s think about what we can do today, the task at hand.

What we can do today as investors is continue our search for value and deepen our understanding of both the businesses we own today and those we’d like to own tomorrow. That is the task at hand - to uncover the pockets of value hidden among an expensive market.

We can’t control the outcome. But at this moment, we can focus on the opportunities in front of us, which are as good as we’ve seen a while.

It's possible that because the competition is so focused on the past—on celebrating the previous champions—that the bar is set low enough for the emerging champions to surprise us. The future may be unpredictable, but both history and the process of creative destruction, warn us that even the most dominant dynasties and unassailable moats eventually come to an end. Follow the process, not the prize. Trust the process. The results will follow.

Sincerely,

Christopher R. Pavese, CFA

Chief Investment Officer

Broyhill Asset Management

This article first appeared on ValueWalk Premium