Askeladden Capital letter for the fourth quarter ended December 31, 2018, titled, “A Better Life.”

Dear Partners,

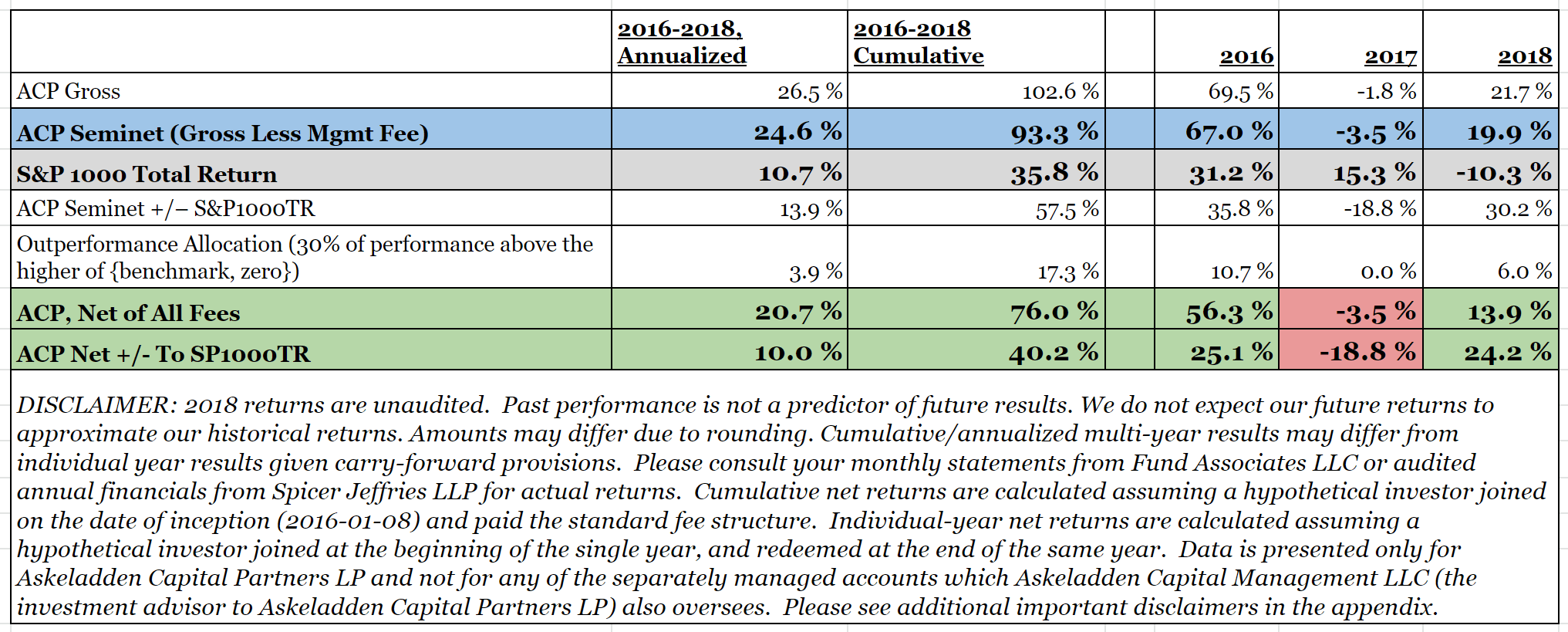

2018 was another exceptional year for Askeladden, making up for a challenging 2017 and then some. Gross returns exceeded 21%, despite our benchmark (S&P 1000 Total Return) declining 10%. This marked the second year (2016 being the other) in which gross returns outperformed the index by more than 30%. This is despite Askeladden using no portfolio leverage in the form of options or margin, predominantly investing in companies with strong balance sheets, and mostly avoiding highly commodity-levered companies.

Q4 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Cumulatively, in the ~three years from 2016-01-08 through 2018-12-31, Askeladden has doubled gross NAV since inception, vs. a cumulative return of ~36% for the index (including dividends, of course). Annualized, we’ve delivered 26.5% gross returns and 20.7% net, vs. 10.7% for the index (again, including dividends).

With the understanding that a month doesn’t mean much, we’re also up double digits to start 2019, with a meaningful positive spread to the benchmark. We believe the portfolio is materially undervalued in aggregate, offering a ~28% three-year forward CAGR assuming our underwritten valuations are correct.

Although we’ve had substantial concentration since inception, we’ve also had a very high hit rate - excluding bookmark/starter positions, most of our positions, regardless of size, that have been held long enough to play out, have delivered extremely strong returns.

Below is a table with more detail that is hopefully helpful.

As usual, a few caveats are in order. First, we don’t believe that these returns are sustainable on either an absolute or relative basis. We would be perfectly happy with mid-to-high teens annualized gross returns on a go-forward basis, although we’re hopeful for 20+. Second, and similarly, there are market environments that would certainly be far less favorable to our performance than the ones we’ve experienced.

Finally, we don’t believe that these returns suggest that there aren’t things to improve. I judge my performance by lead rather than lag measures, and there are several instances - some of which I’ve discussed in past letters - in which my decision-making could have been better. Those who know me know that I take my job seriously - too seriously, some days - and I’m extremely focused on trying to constantly improve and evolve.

Nonetheless, on the whole, it’s a three-year track record to be proud of.

And I’m even prouder of it given the unusual circumstances under which Askeladden was founded.

Business Philosophy

Most of my letters have focused on my investing and analytical worldview – that is to say, helping existing and prospective clients understand our investment process both theoretically and practically. To the latter end, clients have received a specific, private 11-page update on the portfolio along with this letter.

More broadly, however, I think the valuation-sensitive, watchlist-driven Askeladden investment approach is by now reasonably well-understood. At the pivotal three-year mark, with roughly ~$5 million in FPAUM across the fund and SMAs pro forma for verbal commitments from existing and prospective clients, I’ve been asked a different set of questions – namely, what are my future plans for Askeladden?

It’s an important question to answer given the agency problems inherent in asset management. It is in clients’ best interests for funds to stay small, while it is usually in managers’ best interest for funds to scale rapidly. Many small funds that start out with good performance unravel over time, whether due to scaling out of their original opportunity set, or due to principals transitioning from active research to more management-oriented roles as the team grows, and facing the accompanying challenges – new time commitments, skillsets, etc.

My solution to this problem hasn’t changed since inception: I intend for Askeladden to be a low-overhead, one-man-shop into perpetuity. I intend to close Askeladden to new fee-paying AUM when we reach ~$50MM in capital, to preserve our runway for making concentrated investments into attractive small and micro-cap securities. (I would still allow capital additions to offset any capital redemptions after that point.)

In fact, I’ve recently toyed around with the idea of closing a little earlier – say, $40MM FPAUM – to reserve a $10MM block of capacity for friends and family who may want to invest in the future but don’t have the ability today. Many of my personal friends are highly-educated professionals with high future earnings power, but have current financial commitments such as young families or student debt. I’d like to be able to invest on their behalf in the future, but wouldn’t want to do so to the disadvantage of other clients.

To be clear, whether the number ends up being $40something with a reserved block or $50, either would exclude non-fee-paying proprietary capital (i.e. mine and my father’s), and I’m also not planning to return capital once we reach $50MM FPAUM. It’s difficult to know without playing in that world, but my best (conservative) guess is that our strategy’s capacity is probably somewhere in the neighborhood of $200MM. Many similar concentrated small and micro-cap funds have found $200 - $300MM to be the sweet spot, and it’s possible (but not guaranteed) that we could succeed at that level of capital.

So why close to new money at the low level of $50MM? It’s pretty simple – from both a day-to-day operations and higher-level strategic point of view, running a $150MM fund is different from running a smaller fund. It is easier to deal with any potential adjustments or challenges if they come slowly rather than quickly. Moreover, I don’t believe it’s fair to clients to raise capital up to the point of capacity – that would deprive new clients of the ability to compound at high rates of return for 5 – 10 years.

Of course, investment management is an industry full of people who say one thing and do another. One client who funded an SMA this fall asked me point blank how he could know for sure that I wouldn’t change my mind about closing at $50MM when I got there. I’d like to say it’s because I’m the sort of person who wants to do the right thing even if it costs me, but again, that’s easy to say and hard to do.

As with investment philosophy, the easiest way for me to help you understand is to explain our reasoning. To do that, we need to go on a little detour, the point of which will be made clear if you keep reading. Counterintuitively, unlike those of most managers, my incentives are aligned with keeping Askeladden small.

If you don’t feel like a detour, feel free to close up shop here and read the portfolio update instead.

Broken promises… and a war with your bloodstream

Technology was supposed to make our lives easier. When The Andy Griffith Show was still first-run TV, visionaries proclaimed a future wherein we’d only have to work a few days a week.

Instead, each subsequent generation of technology seems to have made our lives busier rather than easier. Paradigm-shifting advances such as the internet and smartphones were supposed to disintermediate productivity from time and location – no longer would we need to be present in physical offices at any given time of day to work on a problem, whether individually or collaboratively.

Rather than enabling us to spend more time sleeping and with our families, and less time sitting in rush hour traffic, these technological advances have perversely extended our workdays. We’re still supposed to have our butts in ergonomic chairs from 9 to 5, but we’re also supposed to be available via Skype/email before and after. Journalists are supposed to write compelling stories… and engage on Twitter. And so on.

So what happened? Where’d the soothsayers go wrong? Mental models make sense of the matter: it’s n-order impacts. In one sense, it’s the same thing as the Berkshire paper mill, investing in new technology with a high ROI and seeing it competed away. We’ve perpetually reinvested the very real productivity savings of technology. Rather than choosing to do the same amount of work with less time and effort, we’ve chosen to do more work with the same amount of time and effort we did before.

Another equally important issue, however, is culture / status quo bias (with a side of local vs. global optimization). For example, too many meetings persist despite the fact that meetings are generally only marginally productive at best. And the worldwide default of physical and temporal colocation – i.e. the dreaded commuter 9-to-5 – persists despite the original reasons justifying it no longer being relevant for the vast majority of knowledge work.

The combination of ever-increasing stress and sleep deprivation is demonstrably worsening our health – a literal war with our bloodstream, as discussed compellingly in books like Dr. Matthew Walker’s “Why We Sleep” (sleep review + notes), Till Roenneberg’s “Internal Time” (IntTm review + notes), and Robert Sapolsky’s “Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers.” Sleep and stress modulate all major diseases known to man.

I want those years back…

Why is any of this important to me – or, more importantly, you?

Because at the end of the day, what we’re all looking for – or, rather, should be looking for – is a better life.

Every person has a different definition thereof; economists might phrase this by saying that every individual has a unique utility function. One acquaintance of mine has no interest in having kids of his own, but has a burning desire to spend his life writing impactful novels for young adults. Others are interested in pursuing excellence in various domains – athletic, professional, etc – at any cost. Others still want to do interesting work, but only to the point where it doesn’t interfere with their ability to pursue personal interests.

There are some people who are truly passionate about their careers, to the point where the work is autotelic – i.e. the career, and all it demands and gives, is the point moreso than any rewards.

For most of us, however, our careers are best viewed through the lenses of tradeoffs. We’re doing work that we enjoy to one degree or another, but work is also something that enables us to achieve goals in other domains of our lives – whether personal, familial, athletic, spiritual, or otherwise.

For example, one man I know gave up the opportunity for a major promotion because it would require putting his two preteen sons through a difficult cross-country move, and deprive him of the opportunity to

coach them in sports. Similarly, another wound down a business he’d spent the majority of his adult life creating, because it demanded too many personal sacrifices that had cumulatively taken their toll.

These were admirable decisions – right globally, if tough locally. Unfortunately, however, we often fail to correctly solve local vs. global optimization problems. Thanks to a relatively predictable set of cognitive biases – especially contrast bias and social proof – it’s easy for us to be led down the wrong path.

As an analogy, it’s often stated for humorous effect that love activates many of the same neural pathways as cocaine – love is a drug, etc etc. This is undoubtedly important for assessing the base rate of decision-making quality when you’re deeply in love, as alluded to in Sunstein/Thaler’s “Nudge” (Ndge review + notes).

However, by inversion, another interesting lesson emerges. Is it more likely that love happens to utilize a pathway our brains created for cocaine… or that hard drugs happen to hijack pathways that evolved for reinforcing positive, life-giving behaviors?

The sheer number of negative external stimuli that can cause addictive behaviors – ranging from those as “mild” as social media, food, or video games to more dangerous ones like gambling, alcohol, and so on – demonstrate how easy it is for us to miss the greater point, to make decisions that feel good locally but lead down the wrong path globally. It is entirely possible to make what seems like the right decision at every given moment, and end up somewhere we don’t want to be whatsoever:

Cardinal crashed into my window, I think he might die.

Plan him a funeral, we’ll read his last rites.

‘cause I know what he saw in that

reflection of light on the glass

was a better life.

- “Cardinals” by The Wonder Years

Our careers are often one such instance of crashing through invisible glass trying to get somewhere warm and safe. When I was in college, I spent a significant amount of time researching what makes us happy – both via personal interviews with those with enough experience to reflect, and more broadly via books, such as Shawn Achor’s “The Happiness Advantage” (THA review + notes) and Karl Pillemer’s “30 Lessons for Living.”

Restricting ourselves to the subset of successful professionals, universally, one of the base rates is that very few people regret not making more money. Nobody, on their deathbed, wishes they’d spent one more late night or early morning at the office. They wish they’d been more willing to take risks – mainly to pursue personal interests, and to spend time with their family and friends.

In fact, a significant body of empirical research suggests that beyond a surprisingly low number (say, $70 - $100K in annual household income), there is an extremely limited (if any) correlation between income and happiness. This squares up with marginal utility theory.

Yet highly-paid professionals – particularly those in the finance industry – succumb to the hardwired human drive for status and prestige. Turney Duff does an excellent job with this in his memoir “The Buy Side,” describing how a small-town Maine kid ended up making all the wrong decisions on Wall Street. Our satisfaction is often not correlated to absolute metrics, but rather relative ones – explaining how bankers can be angry at $2 million bonuses (because their coworker got $2.1 million).

This point was driven home to me when I heard a story about a very well-known, very wealthy hedge fund manager. In public interviews, he stated that what meant the most to him was spending time with his kids. Yet his firm, shortly after those interviews, launched a number of additional products – when he already had

enough money that his grandkids’ grandkids’ would be able to spend their entire lives in the Ritz. A personal friend of his told me he was so busy with work that he only very rarely had the chance to see his family.

Statistically speaking, those are likely decisions he’ll regret someday.

I had that nightmare again…

And here, our wild goose chase brings us back to Askeladden, my golden goose. Not to mention the somewhat counterintuitive reason you should trust that I’m sincere in my desire to not scale: beyond a really very low threshold, I don’t actually care about making money for myself.

I know, I know – I’m in the wrong industry. Allow me to pick up the hedge-fund manager card I just dropped. I’m not Mother Theresa. I’m a capitalist. I wrote the winning essay for the Atlas Shrugged essay contest one year, for crying out loud. Every decision I’ve made in setting up Askeladden has been carefully designed to maximize my self-interest. I just have, perhaps better than most, a thorough understanding of my own utility function – as well as an understanding of how to avoid losing sight of it.

Most people who don’t know me personally assume that my decision to launch Askeladden was somewhere along the spectrum from brave to daring. In reality, it was more desperation than anything else: I didn’t exactly have a lot of other options. I am what you would call unemployable.

It’s not due to my resume. I’ve scored in the 99th percentile on pretty much every standardized test I’ve ever taken (SAT, ACT, GMAT) with minimal studying. I graduated simultaneously from high school and community college at 17 with 84 hours of college credit and a perfect GPA. I completed my MBA, also with a perfect GPA, before I turned 21 – despite working full-time in a white collar professional job since I was 18. Setting aside academics and focusing on soft skills, all of my mentors agree that my capacity for empathy, as well as self-reflection and self-improvement, is off the charts for a 20-something male.

It is thus difficult to craft a plausible narrative in which I wouldn’t be a lights-out asset in most any analytical knowledge-work type role. Yet I have an unusual constraint: I’m a late chronotype and I have higher-than-average sleep needs. In any environment with artificial light exposure, I’m physically incapable of falling asleep before 2 AM, which means that I’m also more or less physically incapable of getting up before 11 (sometimes noon) on any sort of regular basis without severely depriving myself of sleep. (Even on camping trips, 8 or 9 AM is about as early as I wake up without an alarm clock.)

Decades of chronobiology research demonstrates conclusively that you can’t wish or will away your chronotype any more than you can cancer. Yet it turns out that if you can’t or won’t show up at an office at 9:00 in the morning, the rest of your skillset and personality inventory is usually deemed irrelevant.

Even at companies with supposedly flexible schedules, research demonstrates that – controlling for equivalent actual job performance – managers severely penalize those professionals who choose to start their days later rather than earlier. Indeed, being a late chronotype is hazardous to your career trajectory; the corporate environment selects far more strongly for morningness than for talent.

That undoubtedly leads many brilliant late chronotypes to feel the same way I did when I was constantly patronized and talked down to by an early-bird superior. She made me out to be lazy and childish because of something biological I couldn’t change any more than I could change my skin color.

I felt hurt, lost, sad. Angry. Demeaned. Bullied, like high school all over again.

Keep looking down on me, I am more than you’ll ever be… - “Kick Me” by Sleeping with Sirens

I was lucky in that I was homeschooled throughout K – 12, and my first job (as an editor for Seeking Alpha Pro) was work-from-home. So, for most of my life, at least most days, I was able to wake up more or less when I wanted to. When I started working as an analyst and was expected to show up at the office every day, that’s when reality hit me: I couldn’t do this for another two years, let alone 40.

It’s not a work ethic issue: in some senses, my personal life has been on hold ever since I was ten years old. I’ve either intentionally or unknowingly given up many of the typical experiences of childhood and young adulthood in pursuit of my goals. But from a pure health standpoint, it simply wasn’t tenable for me to work as an employee for the vast majority of companies.

What he saw on the reflection of light on the glass…

I learned one important thing while working as an analyst at a former hedge fund sorta-turned family office. The portfolio manager told me that his clients didn’t care if he was working in the office at 3 AM on Sunday, or if he was playing golf on a Tuesday afternoon – both of which he’d done.

No: what his clients cared about was whether or not he made them money. Period. Full stop. No caveats.

And a lightbulb clicked for me. My boss showed up to the office – or the golf course – whenever he wanted, because his relationship with his clients was contractual and performance-based. I had to show up to the office whenever my boss told me to, because my relationship was one of employment, and thus optics-based.

So it immediately became clear that if I wanted the sort of life I wanted to live – i.e. one in which I had control over my time and location – then I had two options.

The first was the approach of getting to “the number.” Also colloquially known in the finance industry as having “bless-you money” (yes, that’s a euphemism), some people take the approach of killing themselves (almost literally) for enough years to walk away with a bank account that provides them with the financial freedom to do whatever they want for the rest of their life.

The second was to create a business for myself in which I leveraged my unique skillset, along with modern technology, to create value for clients who wouldn’t care when and where I did the work to create that value.

The choice between the two was pretty easy. The first requires tremendous and irreversible sacrifices along the way, along with – as a mentor who went through this pointed out – the unsolved problem of what you do at the end. Work, however much we may dislike it some days, provides valuable intellectual stimulation and social interaction for many of us. Retirement isn’t always as easy or fun as it sounds.

The second choice required sacrifices too – primarily, the sacrifice of the stability and certainty of a paycheck, as well as the extreme level of effort and responsibility required to start a new business – but on a discounted net present value type basis, very clearly provided the best of both worlds: the intellectual and social benefits of work, coupled with the lifestyle benefits of being retired.

And so the plan was made to launch Askeladden. Capital raising isn’t a pure meritocracy, of course; pedigree matters, and so does having wealthy family and friends. I had neither. Nonetheless: so far, so good – as stated earlier, pro forma for verbal commitments from existing and new clients, we’ll broach $5 million in FPAUM soon, the majority of which is derived from those who are or have been successful investment professionals themselves. Returns have been phenomenal. And I’ve been happy.

One prospective client noted to me recently that “I know you like to make it sound like you don’t work that hard, but I can tell that you do.” He’s right, of course – in a highly competitive world, there’s no free pass on applying yourself. There is of course the occasional day or week where I binge-watch Modern Family or play through Red Dead Redemption 2, but most of the time I’m pretty locked on to getting stuff done.

But working any amount of hours is far more enjoyable when there’s autonomy involved. I’d rather work 60 hours a week for myself, when and where I want, than 30 for someone else, on their terms. When I launched Askeladden, I posed myself a thought experiment: would I rather spend the rest of my life making $50K/yr on exactly my own terms, or would I rather make a practically unlimited amount of money but sell my freedom to do it? The answer was easy when I framed it that way: the first. What I wanted was…

... a better life.

Was all of that context entirely necessary? Perhaps not. But I think the depth is helpful in answering the question that the one prospective client asked point-blank, and many others undoubtedly wondered: in an industry all too often characterized by duplicity and greed, how can you trust that I’ll stick to my guns and close at a small capital base, ensuring that we don’t scale out of our opportunity set (or my skillset?)

The most compelling answer: it’s in my best interest to do so, based on my unique utility function. Incentives are too often simplistically reduced to money; there’s more to the story. Relevant variables for me:

- Income above a certain point (say, 95th percentile HHI, or ~$250K/yr) holds very little value for me.

- I won’t trade ANYTHING for sleep (both amount and timing) on a regular basis.

- I will trade off very few things for day-to-day schedule control.

- I like long-term, qualitatively-oriented research.

- I don’t like compliance / administrative / operations / trading, and I don’t like managing people.

Again, with the critical factor being that I’m optimizing for being happy, rather than wealthy, scaling too large makes no sense. Universally, all the investors I’ve known who’ve run large funds have noted the inverse correlation between fund size and time spent on research. Larger funds naturally require more operational/compliance/administrative work, more marketing, and more time spent managing teams.

So a larger fund would make me more money… which wouldn’t do much for me… but it would require me to spend a lot of time on stuff that I don’t want to spend time on, and am not particularly good at. Which would make me sad. It would also probably require me to get up before 11 more often than once a month, which would make me very sad. We’d be back to “the number” – get rich, then get out. If that’s what I wanted, there are much easier ways to get there than trying to launch and run my own fund.

Finally, and critically, the larger the fund, the fewer – and more picked-over – the opportunities that are available. Although I’m theoretically willing to invest in a company of any size – I won’t turn down Google if it trades at five times free cash flow – I’ve repeatedly found, over the course of my five years as a professional investor, that smaller companies tend to have greater frequency and magnitude of favorable mispricings.

Many Askeladden portfolio companies, even those with larger nominal market caps, have accessible floats well below $300 million, and in some cases below $100 or $200 million, which creates an obvious mathematical liquidity challenge for larger funds that want to take concentrated positions.

My business will succeed or fail based on my performance. I don’t have a fancy pedigree or brand name to fall back on. I’m not going to impress you with my Levi’s and Chuck Taylors. Given that I’m trying to run Askeladden as a sustainable lifestyle business for decades, there’s no point in flying too close to the sun and burning our wings.

Of course, all other things being equal, more money is better than less – but all other things are rarely equal, and the same analytical process that leads me to consistently identify and invest in undervalued companies leads me to believe that it’s unlikely that Askeladden would be either operationally or strategically sustainable, in a manner that is acceptable to me, if it scaled to a very large size.

In Conclusion

I haven’t actively marketed Askeladden during its first three years, other than posting content online and making it readily available to anyone interested. After careful consideration, I am planning to start marketing more actively in a very selective way, which I will discuss in more detail in the next letter.

Why? Askeladden has a credible value proposition; the quality of our thinking and the unique effectiveness of our process is self-evident from the body of work we’ve cumulatively presented. The same analytical capabilities that have led me to enjoy a better life can help others achieve a better life for themselves – whatever their individual utility functions may be.

Key in on “very selective,” however – I’ve turned down capital in instances when the client was not a good philosophical or personality fit for Askeladden, and I am completely willing to do so in the future as well, no matter the check size. Indeed, half a year elapsed between me reading Ogilvy on Advertising, originally considering ways to actively market Askeladden, and finally taking a new step that will help us do so.

While it would be nice to have a larger operating budget both personally and professionally, it’s much more of a want than a need – Askeladden as a business is meaningfully cash flow positive and as a single 25 year old who lives at home in a very low cost of living metro (D/FW), my personal cost structure is very lean.

The things I like in life (kale, EVOO, coffee, backpacking, books) tend to be pretty cheap. Rarely do I really want something and feel like I can’t afford it. I live a good life. I’m not eating ramen (unless it’s the tonkotsu kind.) Moreover, I have ample savings and no debt. There will come a day when I’ll have a family and need to be able to support them, but that day is quite far away.

As such, I don’t have any specific capital-raising targets: I’m focused on building Askeladden well rather than quickly. There is substantial intentionality here. I want my focus and time to remain firmly on research – it’s the goose that lays the golden eggs – and I’m very sensitive to my lifestyle being compromised.

I’d rather maintain those two constraints and scale somewhat more slowly than abandon them and scale more quickly. Capital is far more plentiful than alpha. $50 million is, in the grand scheme of things, not a lot of capacity – so the leverage is on my side of the table. As such, I’m willing to take as long as it takes to get to $50MM on terms I find acceptable, although I have a hunch that it’ll be sooner rather than later.

Three years of experience ultimately leaves me with substantially more confidence than I had when I started: confidence that we have a sustainable and repeatable process for generating superior investment performance, and confidence that our process – and our uniquely transparent communication style – resonates with financially sophisticated clients who are often successful investment professionals themselves, or have previously invested in name-brand funds (the type run by famous “superinvestors.”)

This confidence, however, is not hubris. I remain focused on continuing to expand and strengthen our circle of competence. I use every opportunity I get with older and more experienced investors to learn something new: about a skill like interviewing management teams, about the history of a certain industry or business model, about the challenges I’ll face as my fund scales. There’s lots to learn. I’m just getting started.

In closing, I am grateful to all Askeladden clients for entrusting me with their capital, a responsibility that I take very seriously. More than anything else, I am grateful to you for enabling me to live exactly the life I want to live, and – in turn – I hope that my efforts will help you do the same.

As always - westward on. It’s our manifest destiny (in case you were wondering why I always close letters with that phrase.)

Samir

This article first appeared on ValueWalk Premium