Excerpted from The Geometry of Wealth by Brian Portnoy, published by Harriman House. Available wherever books are sold.

Readers can win a copy of the book by entering the contest at this link and embedded below.

An important distinction when thinking about making good decisions is whether we actually have any choice to begin with—or whether we want any. At times in life, we have a great deal of discretion. We choose to eat out instead of staying in; we then choose one of many restaurants; and we then choose whatever we’d like from an extensive menu. In an opposite scenario, we are obligated to attend someone’s dinner party and eat whatever we’re served alongside people we didn’t choose to be with.

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc, Also read Lear Capital: Financial Products You Should Avoid?

The Geometry of Wealth: How To Shape A Life Of Money And Meaning by Brian Portnoy

This type of choice regime—discretion vs. not—is something we encounter daily, in all life’s domains—consumption, health, work, transportation, education, money. Its structure and its consequences are usually trivial. Our spouse’s friend may be a dreadful cook, but we’ll survive an overdone steak.

In some areas it’s not trivial. For example, some of us participate in our employer’s retirement plan. A small portion of our regular paycheck is automatically deposited in the plan. This is effectively putting our investment decisions on autopilot. Those who opt into retirement plans usually don’t then later opt out. In contrast, most other types of investing are discretionary, in which you can buy and sell as you see fit.

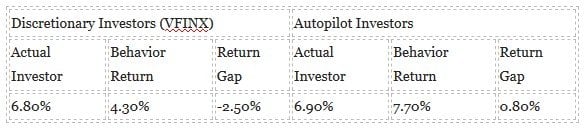

One striking example of the consequences of these two approaches will bring the point home. In this case, different investors in the exact same fund over the exact same time frame had dramatically different outcomes:

Investment A over 10 years -> Good Outcome Investment A over 10 years -> Bad Outcome

How could this be? The difference is determined by those who have discretion over their trip versus those on autopilot.

When we compare discretionary versus autopilot versions of the same investment, we often observe wildly different investor outcomes. Take as an example the world’s largest mutual fund, the Vanguard 500 Index Fund. With about $620 billion in assets, the fund comes in two different formats. The portfolio is identical in each, but one version is held in autopilot retirement accounts, the other in discretionary accounts. The only practical difference between the two funds is an immaterial difference in cost (a small fraction of a penny on the dollar).

As would be expected, the investment performance of the two funds is nearly identical. Over a 10-year span, the auto-pilot version (VINIX) returned 6.9% per year while the discretionary version (VFINX) returned 6.8%—a tiny gap explained by that small fee differential.

When we dig into the numbers, the picture grows more interesting. The behavior gap for the discretionary fund is wide. Compared to the actual 6.8% return, the average investor in the fund earned only 4.3%. Because this time span includes 2008, much of the behavior gap is explained by impulsive selling during the crisis and then failure to resume investing after markets calmed down.

The Benefit of Constraint

Autopilot investors fared much better. While VINIX returned 6.9% per year, the average autopilot investor made 7.7% per year—a negative behavior gap! Why? Because investors in VINIX are dollar cost averaging into the market during good times and bad. They were less likely to sell in 2008. They buy more shares when the market is lower and fewer when it is higher; a slight twist on buying low and selling high. As a result, investors in VINIX outperformed their own fund.

All in, autopilot investors had a much better experience than discretionary investors. The real dollar consequence of this good versus bad decision-making is large. Here, the average $100,000 investor in VFINX ended up with $160,630 over the following decade, compared to $260,087 in VINIX—a 62% difference. This isn’t pie-in-the-sky finance. These are significant dollars that can make a difference in our lives.

In this case, one group of investors wasn’t “smarter” than the other. They weren’t more likely to have an MBA or a degree in finance. Instead, one group had a lot of flexibility—and abused it. The other forfeited that choice by going on autopilot and came out way ahead.

With investing, an itchy trigger finger invites trouble. When markets get shaky, we can’t but help feel the urge to bolt. And once we step aside, we greatly underestimate the fortitude it takes to get back in. This is only natural—our brains are wired this way.

However, impulse control is, to some extent, manageable. Through proper parenting, coaching, and socializing, individuals can buttress their willpower. Better outcomes are possible, even though much of the available data point to worse ones. As we just saw, one solution is to eliminate discretion altogether. When we sign up for automatic savings plans, we tend to achieve much better outcomes.

One of the most successful savings programs in U.S. history has done just that. By a small but important design tweak, the behaviorists behind the “Save More Tomorrow” program have driven billions of dollars in extra savings by individual investors. That tweak was introducing “negative consent” to corporate retirement plans: Rather than asking people to opt in to a regular savings plan, they automatically enrolled them and then asked people to opt out if they so chose. The choice set and constraints were identical, but one paradigm has worked much better than the other.

Oftentimes we don’t have the luxury of such structures, nor self-control. In these cases, it’s important to partner with good counselors and associate with good role models. We take direction well from those we respect; and we mimic the behavior of those we like. Individuals who work with good financial advisors tend to have better outcomes, not because those advisors are more market savvy, but because they are skilled at providing a check on bad investment behavior, such as selling during market choppiness. Likewise, if we run with a fast money crowd, we’re more likely to try to keep up, especially in terms of conspicuous consumption: My neighbor just got that new Audi, so why shouldn’t I upgrade? Associating with those who have healthier money habits produces healthier outcomes. The classic money book, The Millionaire Next Door, told tales of frugal millionaires who lived in communities where there was less urge to keep up with the Joneses.

Even more deeply, we strive to transform decisions into habits: Rendering sound money decisions into routines that we no longer think about. We just do them (such as regular savings) or don’t do them (such as living beyond our means). Finding better habits is an important expression of adaptive simplicity, for it means that we can eliminate the psychic strain of self-control, frequent decisions, and the additional consumption of (often useless) information.

When the noise in our minds collides with time’s quiet expanse, we struggle. We hold the keys to our own long-term success, even though we sometimes forget. Regular, consistent, disciplined investing is awesome—especially when we’re not thinking about it. A much better experience with money is within anyone’s reach.

About the Author:

Check out the contest