The enterprise of coastal litigation in Louisiana and all that it entails is best understood in the context of a business model. In simplest terms law firms file suit against oil and gas companies for profit. The model has three principal components: a premise for litigation, a set of plaintiffs through which to file the lawsuits, and a modus operandi designed to insure optimal treatment of the lawsuits in the judicial and political arenas. The implementation of this model began in 2012 after legislation had substantially restricted the traditional “legacy lawsuit” model and the Deepwater Horizon disaster revealed the potential magnitude of judicial judgements and settlements that could be afforded by large oil and gas companies. Since its implementation, the coastal litigation business model has fundamentally changed the nature of politics, the judicial system, the economy, and the coastal restoration program in Louisiana.

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc, Also read Lear Capital

The premise

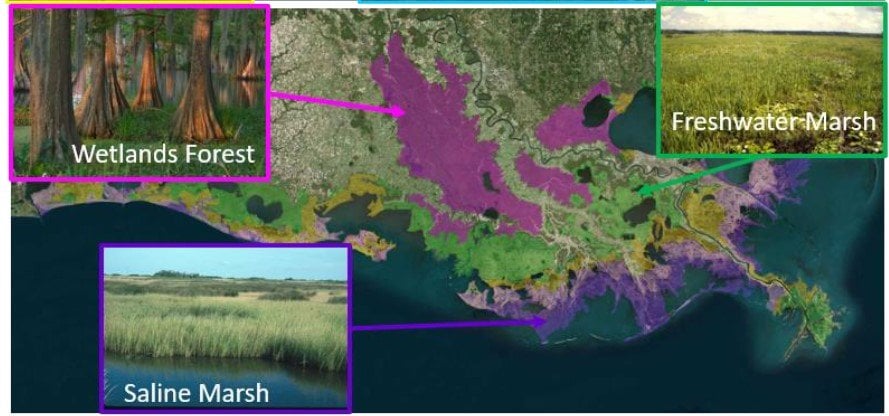

To some extent coastal litigation arose organically from the general public perception about the causes of coastal wetlands loss. The law firms that have filed the coastal lawsuits could be afforded some credit for recognizing fertile ground for the business opportunity. A poll of a representative portion of the residents of coastal Louisiana would be likely to reveal a set of commonly held beliefs about wetlands loss:

- The wetlands of south Louisiana were built up in a continuous and progressive increase in land area by the deposition of sediment by the Mississippi River over the last 6,000

- Until the middle part of the 20th century these wetlands provided a protective buffer to most residents of coastal Louisiana from storm surge generated by

- The loss of hundreds of thousands of acres of wetlands over the past few decades is an unprecedented event in the history of the

- Wetlands loss has primarily been caused by coastal erosion caused by saltwater intrusion carried into the wetlands by oil and gas

- Because wetlands loss was primarily caused by the action of humans, it can also be reversed by the actions of

The coastal lawsuits are fundamentally based on and reliant on this set of beliefs, as they are explicitly expressed in the introduction of the first coastal lawsuit:

Board of Commissioners of the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-E, et al. v. Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, LLC, et al., No. 2013-6911, Civil District Court for the Parish of Orleans, Louisiana

“Coastal lands have for centuries provided a crucial buffer zone between south Louisiana's communities and the violent wave action and storm surge that tropical storms and hurricanes transmit from the Gulf of Mexico. Coastal lands are a natural protective buffer, without which the levees that protect the cities and towns of south Louisiana are left exposed to unabated destructive forces.

This natural protective buffer took 6,000 years to form. Yet, as described below, it has been brought to the brink of destruction over the course of a single human lifetime. Hundreds of thousands of acres of the coastal lands that once protected south Louisiana are now gone as a result of oil and gas industry activities– all as specifically noted by the United States Geological Survey.”

Using the existing popular narratives as a premise for litigation has proven to be a very effective method to maximize popular and political acceptance of suing oil and gas companies, and the law firms that have filed the coastal lawsuits have extended the narratives to include the concept that litigation is an effective means to address wetland loss. Any potential jury members in the coastal parishes are predisposed to believe the contentions of the lawsuits. Politicians involved in the mechanics of filing the suits are provided a degree of political cover by the narratives in the face of the obvious impacts on their local economies brought on by suing oil and gas companies. The problem with the narratives and by extension the premises of the lawsuits is that they are all scientifically incorrect. None of contentions of the lawsuits are supported by any significant amount of current scientific research. A scientifically accurate restatement of each of the popular narratives would read something like this:

- The wetlands of south Louisiana at the surface today represent about 15% of the total wetlands area that was built by the Mississippi River deltas over the past 6,000 Most of the historical deltas of this era have already subsided below the surface.

- The ability of low-lying marshes to buffer against storm surge is a subject of some Once the marsh is under a foot or two of water, it loses most of its ability to buffer surge. Certainly, when there were vast cypress forests across the area that is now Breton Sound, the inland areas were effectively protected. That protection was lost at around the time Europeans first entered the area by the subsidence of the cypress forests.

- The loss of wetlands over time is a natural component of the delta It can reasonably be estimated that 20,000 square miles of wetlands area was lost to subsidence over the past 6,000 years

- The 2017 Master Plan for restoring coastal Louisiana has two main scientific appendices that address the causes of wetland One is on subsidence and one is on sea level rise. There is very limited discussion of oil and gas canals as a cause of wetland loss in the 2017 Master Plan, and it certainly not treated as a principal cause.

- The premise that humans caused wetland loss and therefore humans can reverse it results in a substantially different approach to coastal restoration than a recognition that wetland loss is primarily due to the natural forces of Continuing to promote this premise actually impedes the effective implementation of coastal sustainability planning.

The contention of the law firms filing the coastal lawsuits that litigation is an effective way to address wetland loss also appears to lack any degree of substantiation. Many of the same law firms making this contention have been involved in “legacy lawsuits” against oil and gas companies for years. This article taken from the WWL-TV investigative series “Tainted Legacy” found that of the more than 360 legacy lawsuits filed against oil and gas companies since the 1990s, 137 of the properties in question have been verified by the state Office of Conservation to have contamination that warranted cleaning up, and of those 137 properties, 12 have been cleaned up to state standards. In most cases there was no requirement for the recipients of judgements or settlements in the cases to use the money to remediate the claims. Legacy lawsuits have proven to be a very effective way to transfer money from oil and gas companies to plaintiffs and their attorneys, but a very ineffective way to make any significant changes to the environment. There is no evidence that litigation would be an effective way to fund coastal restoration projects.

There is very little vocal support for coastal litigation outside of those that intend to benefit financially from it. Opposition to the lawsuits comes primarily from business and industry interests (which is to be expected), but also from within government and academia.

Ed Richards, Director of the LSU Law School Climate Change Law and Policy Project wrote in this essay posted on his blog:

“This [coastal] lawsuit is based on the mythology that the Mississippi delta is in a steady state world and that, but for the actions of bad people – the oil industry, the Corps of Engineers – everything would be fine. The plaintiffs’ claims deny climate change and the best coastal science. The defense of this case should be seen as an opportunity to bring the best science to bear on questions of the Louisiana coast and its future in a changing world.”

Chris Dalbom, Program Manager of Tulane’s Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy said in this interview on WWNO Radio’s Coastal News Roundup:

“Using litigation or the injuries [involved] to fund coastal restoration is no way to go about things. It is definitely not a reliable source [of funding]. Even though at this moment it seems like the closest thing to a plan that we have when it comes to a lot of our funding questions, it is certainly no way to continue.”

State Senator Norby Chabert said in this op-ed letter :

“These lawsuits attack the companies that are currently the largest contributors to our coastal restoration funds. If we truly want to grow and maintain our coastline, we should be doing everything possible to encourage the industries to locate and expand in our state.”

The plaintiffs

There is substantial evidence that once the concept for the premise of the coastal lawsuits had been established, the law firms that eventually filed the suits actively solicited a number of public and private entities to act in the role of the plaintiffs. This approach to litigation is a significant perturbation to the commonly accepted basis of jurisprudence in which a plaintiff seeking to redress a grievance against a defendant retains the representation of legal counsel to carry out litigation conceived of and largely defined by the plaintiff. In the coastal lawsuits it appears that the entire enterprise of the litigation, from the conception of the premise of the lawsuit, to the manner by which legal counsel was selected, to the execution and sustenance of the litigation was implemented by the law firms. The nominal plaintiffs in these cases were essentially “along for the ride”.

The original coastal lawsuit filed on behalf of the Board of Commissioners of the South Louisiana Flood Protection Authority–East was removed to U.S. District Court where it was dismissed by Judge Nannette Jolivette Brown on February 13, 2015. The dismissal was upheld by the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear any further appeal. This lawsuit is not considered in detail here.

All subsequent coastal lawsuits were filed on behalf of parishes acting in the nominal role of plaintiff under the provisions of the Louisiana State and Local Coastal Resources Management Act of 1978 (SLCRMA). There are eleven parishes with approved coastal programs under SLCRMA. Each parish must complete a process to obtain federal and state approval to participate including the publication of a coastal zone management program. On November 8, 2013 the law firm Talbot Carmouche & Marcello filed 21 lawsuits in the 25th Judicial Court on behalf of Plaquemines Parish. It would be impossible to conclude from reading the Plaquemines Parish Coastal Zone Management Program document that parish officials considered oil and gas activity to be a principal cause of wetlands loss prior to the filing of this lawsuit. A reference to canals is fourth in a prioritized list of environmental concerns behind regional subsidence and sea level rise, local subsidence related to compaction, and erosion of barrier islands and shore – all natural causes of wetland loss. The reference to canals is not even exclusive to oil and gas canals. It seems highly improbable that parish officials sought out legal representation to file lawsuits against oil and gas companies for wetlands loss under SLCRMA when the parish document that qualified it to participate in the program does not consider oil and gas activity as a primary cause of wetlands loss.

The fact that 7 lawsuits nearly identical to those filed on behalf of Plaquemines Parish were filed three days later by the law firm Burglass & Tankersley, LLC in the 24th Judicial Court on behalf of Jefferson Parish indicates that the attorneys for the law firms were working together to pursue the litigation. The degree to which these law firms controlled the entire processes of filing the lawsuits is evidenced by the fact that the language of the original resolutions taken up by each parish council to retain legal counsel is also nearly identical. It seems plainly obvious that the law firms worked together to write the resolutions that were introduced by parish council members at regular council meetings in May and June of 2013. If this were the case, it would suggest that the language of the resolutions, which defined the requirements for the qualifications of the law firm and the process for selecting a lead law firm, was written by the law firms that were pursuing the opportunity to file the lawsuits. It would also suggest that the language defining the requirements and process of selection was intentionally written to favor those law firms.

The evidence that the law firms actively solicited Plaquemines and Jefferson Parishes to act in the role of the plaintiff for coastal litigation is consistent with the general conception that the firms solicited participation from a wide range of public and private entities, including all other coastal parishes, levee boards, and private landowners. Discussions with the management of large private landowners such as the Delacroix Corporation or the Biloxi Marsh Lands Corporation would be likely to reveal the extent to which they were “wined and dined” by the attorneys in an effort to convince them to participate as plaintiffs.

Once these lawsuits were filed they came under the full control of the law firms. The law firms have continued to advance the existing lawsuits even as the parish governments, acting in the role of plaintiffs, have opposed them. At the November 12, 2015 Plaquemines Parish Council Meeting the Council passed Resolution 15-389 stating in part:

“NOW, THEREFORE: BE IT RESOLVED BY THE PLAQUEMINES PARISH COUNCIL THAT it hereby directs the law firm of any counsel providing assistance in pursuing claims described herein, including, but not limited to, Carmouche and Associates, LLC d/b/a Talbot Carmouche & Marcello; Connick & Connick, LLC; Cossich Sumich, Parsiola & Taylor, LLC and Burglass & Tankersley, LLC., to take those actions necessary, including, but not limited to, the preparation and filing of relevant motions and orders, to immediately effectuate the dismissal of the lawsuits and actions filed pursuant to the Coastal Zone Management Act and Ordinance 13- 210; and otherwise to provide with respect thereto.”

There is no evidence that the law firms took any action to follow the directives of the plaintiff in this case. They instead appear to have pursued other means by which to regain control of the litigation process, as will be discussed in the next section. This resolution came just days before the election of Governor John Bel Edwards, and the law firms presumably knew that things were about to change. There was a similar situation in Vermillion Parish in 2016. After the District Attorney for the Parish filed a coastal lawsuit, the parish council voted unanimously in opposition to the litigation.

The progress of the Plaquemines and Jefferson lawsuits through the legal system and the addition of new ones filed on behalf of Cameron, Vermillion, St. Bernard and St. John the Baptist Parishes is complex and complicated to understand. In the four years following the filing of the initial parish lawsuits it appears that the law firms expanded the business model of pursing litigation against oil and gas companies to include aggressive engagement in the political and public relations arenas in support of the lawsuits.

Modus operandi

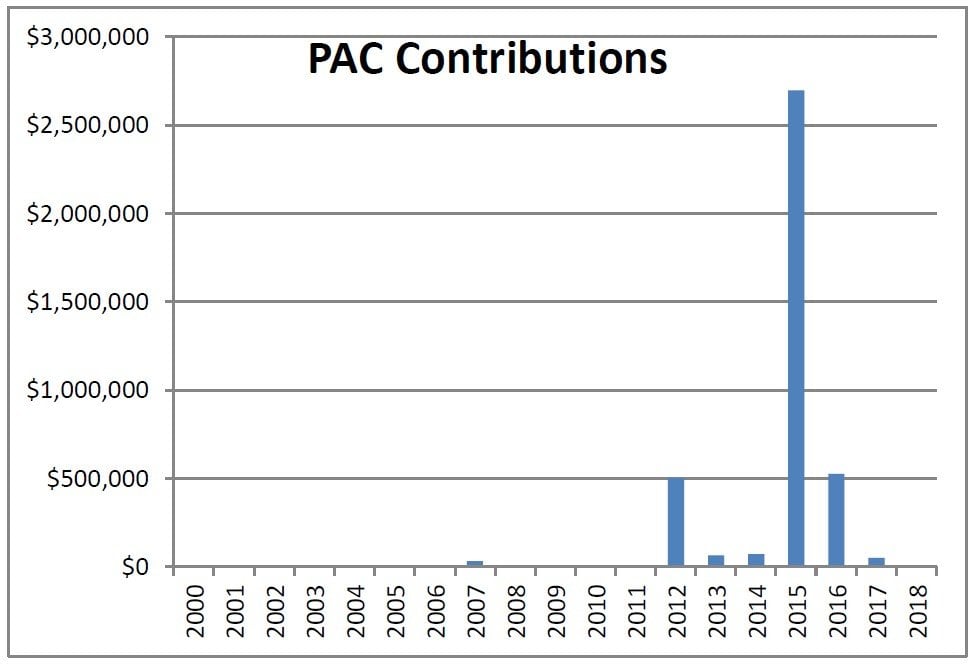

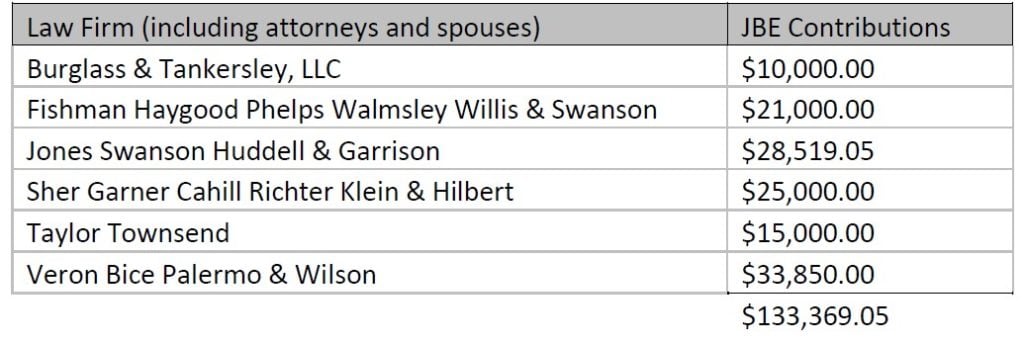

The primary law firms behind coastal litigation and the attorneys they employ had been active in political campaign contributions since the turn of the century, but the magnitude of the donations and their impacts exploded after the filing of the first coastal lawsuits. It would appear that the use of money in supporting political candidates has become an essential part of the coastal litigation business model. In total 32 attorneys and their spouses with the 10 major law firms have made almost $7 million dollars in campaign contributions since 1998, as determined from data reported to the Louisiana Ethics Administration Program . That total includes $2.94 million in direct contributions to candidates, $2.61 million in contributions to political action committees (PACs), and $1.35 million in zero-interest loans to PACs. In a story on PAC spending political analyst Jeremy Alford said that level of spending by the coastal lawsuit attorneys was “previously unheard of in Louisiana politics.” A summary of all contributions totaling $10,000 or more received by (or benefitting) candidates since January 1, 2012 from these attorneys reveals the priority objectives of the contributions.

aaa

Since taking office in January 2016, Governor John Bel Edwards has significantly facilitated the business of coastal litigation. On May 13, 2016 the Governor called a meeting with oil and gas industry leaders and executives to request that they settle the pending lawsuits. Then-president of the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association (LOGA), Don Briggs, was quoted saying that Edwards had suggested in the meeting that “Louisiana faces spending $100 billion on coastal restoration over the coming decades and that the industry should pay a sizable amount of that.” In a letter responding to the meeting Briggs and Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association President, Chris Johns, said:

“The lawsuits were filed by profit-motivated lawyers, and are not a funding mechanism for the coastal master plan or for state or local government budgets. The current legal climate in the state threatens jobs at a time when our state can ill afford economic setbacks.”

On August 12, 2016 Edwards hired a group of attorneys to represent the State in the coastal lawsuits with no-bid contracts. These lawyers were all from coastal litigation law firms that were also major contributors to the Edwards campaign.

On September 20, 2016 Edwards sent a letter to all coastal parishes including the sentence “We encourage you to consult with your private counsel and file such a suit, in which [DNR] Secretary Harris will then intervene. Should you not do so within thirty (30) days of the date of this letter, Secretary Harris will do so.” In other words, the governor instructed all twenty coastal parishes to file lawsuits against the oil and gas industry or the State would do in on their behalf. It is hard to imagine a more direct and effective facilitation of the business of suing the industry than an order from the governor. Edwards’ demand was not well-received by all parishes. In a letter from the Parish Presidents of Terrebonne and Lafourche they requested not to be made a part of the lawsuits.

The dynamics of the 2015 gubernatorial election are generally represented as a surge of anti-Vitter PAC spending allowing Edwards to come from behind against a split Republican field. While it is true that virtually all of the $2.24 million contributed to the Gumbo PAC and the Louisiana Water PAC by coastal lawsuit firms and their attorneys were used for often vicious attack ads against Vitter, his personal failings were not the real issue. In an interview with Bayou Buzz, Trey Ourso - the chairman of Gumbo PAC, made it clear that in addition to his job as campaign manager for Charlie Melancon (in the 2010 race for U.S. Senator against Vitter), he also did lobbying work for the “trial bar”. Ourso said that in meetings with plaintiffs’ attorneys they suggested forming a PAC to him. It appears that the impetus for this meeting was David Vitter’s announcement at a LOGA meeting that he intended to pursue tort reform. In retrospect it would be more correct to state that the big PAC spending in the 2015 governor’s race was in support of litigation, and in particular coastal litigation. The attacks against Vitter were typical down-and-dirty politics, but the real agenda was to insure that coastal litigation was protected. John Bel Edwards became the beneficiary of this strategy, and his efforts to advance the litigation after taking office suggest that he is indebted to those that funded the PAC spending.

In a clear second place on the prioritized list of campaign contributions are the Supreme Court justices. Political analysts generally credit attorney John Carmouche with single-handedly getting Justice Jeff Hughes elected in 2012. Carmouche and his father Donald and their law firm collectively contributed

$520,000 to the Citizens for Clean Water and Land PAC between June and December of 2012. The website for the PAC lists a single candidate endorsement – Jeff Hughes. It is not clear that this strategy of over- the-top financial support for a Supreme Court candidate worked. Hughes was forced to recuse himself from any cases involving coastal litigation. The attorneys have pressed on with this component of the business model however. Coastal litigation attorneys spent heavily in the 2016 election of Supreme Court justice Jimmy Genovese. The sheer magnitude of these campaign contributions is an obvious source of concern, not only for the viability of the political system, but for the viability of the judicial system. In an interview with PBS Supreme Court Justices Anthony Kennedy and Stephen Breyer were asked about the impact of campaign contributions on the judicial system:

“A poll conducted by the Texas state supreme court and the Texas state bar association found that 83% of the public think judges are already unduly influenced by campaign contributions. 79% of the lawyers who appear before the judges think campaign contributions significantly influence courtroom decisions. And almost half of the justices on the court think the same thing. Isn't the verdict in from the people that they cannot trust the judicial system there anymore?

Kennedy: This is serious, because the law commands allegiance only if it commands respect. It commands respect only if the public thinks the judges are neutral. And when you have figures like that, the judicial system is in real trouble. And that's why we should have a national conversation about it.

Breyer: I agree completely. Independence doesn't mean you decide the way you want. Independence means you decide according to the law and the facts. The law and the facts do not include deciding according to campaign contributions. And if that's what people think, I couldn't agree with you more. The balance has tipped too far, and when the balance has tipped too far, that threatens the institution. To threaten the institution is to threaten fair administration of justice and protection of liberty.”

The next tier of campaign contributions from the coastal litigation law firms on the prioritized list between

$15,000 and $40,000 also slants heavily toward judges. From a business perspective these contributions to Judicial District and Appeals Court judges would appear to be investments to attempt to insure favorable treatment of the coast lawsuits as they follow an inevitable course through the legal system toward a final determination at the Supreme Court.

The four highlighted candidates on the list that received campaign contributions of between $10,000 and

$15,000 from the attorneys are of particular interest because of the roles they play in the coastal litigation process. 25th Judicial District Judge Michael Clement will be presiding over the first of the parish lawsuits some time in 2019. The magnitude of the contributions from the attorneys for a district judge sticks out because the majority of the contributions were made in March of 2014 after the Plaquemines lawsuits had been filed, and in an election in which Clement was an unopposed candidate who was automatically re-elected without appearing on the ballot. John Baker Jr., chairman of the Center for Legal Integrity and LSU professor emeritus of law, is quoted saying that he is wary of campaign contributions made to judicial candidates.

“In an elective system for judges, people should be able to give money to judicial candidates," he said. "But judges ought to have to recuse themselves from cases involving donors who give above a certain amount. I don’t know what that amount should be."

At the very least Baker suggested Clement should recuse himself from hearing the case due to receiving campaign funds from Carmouche and have a judge brought in from elsewhere.

The contributions to Plaquemines Parish councilman Benny Rousselle are also somewhat anomalous in that they consist of ten individual contributions of $1,000 made over a 30-day period (seven on the same day) by coastal litigation attorneys and their spouses in the summer of 2017. This was at time that was not in sync with the election cycle. Rousselle only incurred about $2,600 of campaign expense in 2017, and half of that was for a fundraiser. Rousselle has been a vocal supporter of coastal litigation, and he introduced Resolution 16-129 in April of 2016, which rescinded the Council’s decision to instruct the attorneys to “immediately effectuate the dismissal of the lawsuits” five months earlier. St. Bernard Parish President Guy McInnis also stands out as the biggest recipient of campaign contributions at the parish level. This was a source of concern for parish residents because of the way that the parish lawsuit came about. Instead of the parish council voting directly on a resolution to participate in the coastal lawsuits, they voted on Resolution 1616-08-16 to give McInnis the sole authority to make that decision. The law firm of Talbot Carmouche and Marcello filed suit on behalf of St. Bernard Parish less than two months after this resolution passed, and six days after Governor Edwards’ letter to the coastal parishes instructing them to file suit. As was the case with Plaquemines Parish, the St. Bernard Coastal Zone Management document indicates that prior to the filing of the lawsuit parish officials did not consider oil and gas activity to be the primary cause of wetlands loss in the parish. The section of the report on geology lists canal construction third behind erosion and subsidence in a list of causes. It is universally recognized that the overwhelming majority of land loss due to canals in the parish is associated with the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet and the Intracoastal Waterway. This section also describes in some detail how the marshes of the parish are in the natural destructive phase of the delta cycle. It would appear that the decision by McInnis to file suit was not based on an actual belief that the oil and gas industry was responsible for land loss.

The process by which the St. Bernard lawsuit came about may warrant further investigation. It has been suggested that there were ethical breaches in which the council met in executive session with the attorneys, and a straw poll of their vote was taken in that session. The resolution was taken up and voted on in the regular (public) council meeting without discussion. Council members that voted against the resolution may be willing to talk about the process.

The final highlighted entry on the prioritized list of campaign contributions is Tangipahoa Sheriff Daniel Edwards. Edwards is out of place in having received $10,000 from the coastal litigation attorneys because unlike everyone else on the list, he is in a jurisdiction in which there is no evidence any of the attorneys have ever done any business. There has never been a legacy lawsuit in the Tangipahoa Parish, and it is certainly not in the coastal zone. There are no other contributions from the attorneys to any politicians in nearby parishes. It would appear that the contributions to Daniel Edwards were more likely intended to curry favor with his brother, the governor.

In the end, nobody has said it better than John Carmouche himself. He is quoted in this story from the Business Report: “We are not tree huggers. We are business people”. Truer words have never been spoken. The coastal litigation attorneys are business people; they are not environmentalists. Their business is suing oil and gas companies for profit. In a free capitalist society every business is entitled to pursue making a profit, but that does not insure the legitimacy of their intent. There is no evidence of any kind that litigation is an effective means to fund coastal restoration. There is substantial evidence that:

- Legacy lawsuits have proven to be a very ineffective way to remediate the environmental problems associated with oil and gas operations abandoned by individual

- The attorneys involved conceived of the coastal lawsuits as a for-profit business venture and had complete control over every aspect of their

- The foundational premises of the coastal lawsuits are not scientifically

- The plaintiffs in the coastal lawsuits were solicited for participation by the attorneys

- None of these parishes would have been likely to initiate litigation without

- The attorneys involved have significantly impacted the political system in Louisiana in an effort to advance the business of coastal

- The attorneys involved have significantly affected the processes of the judicial system in Louisiana in an effort to insure favorable treatment of their lawsuits in

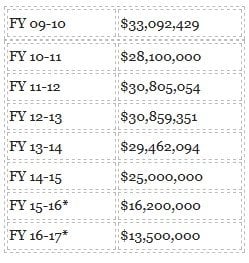

The stunning reality is that all of these impacts on political and judicial systems and the public’s perception of the causes of wetlands loss and the role of the oil and gas industry pale in comparison to the impacts that coastal litigation has had on the coastal restoration program. This presentation was given by Chip Kline, Chair of the Coastal Restoration and Protection Authority (CPRA) at the America’s Wetlands Foundation Coastal Leadership Roundtable Meeting in 2016. It shows on slides 6-8 that the entire CPRA operating budget is derived from a dedicated stream of oil and gas mineral revenue:

Revenue Collection History and Projections

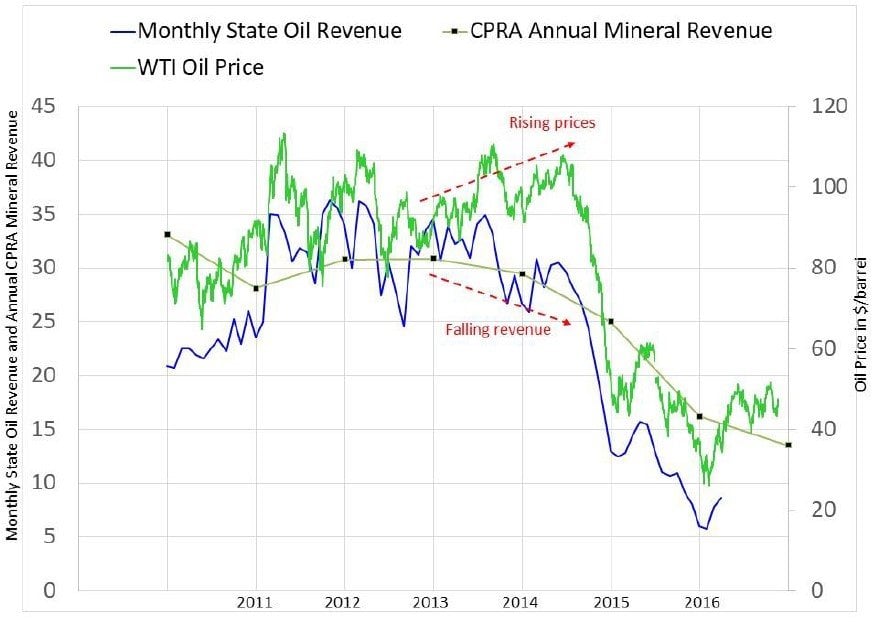

This table taken from slide 7 shows that the estimated cash flow from mineral revenues in fiscal year 2016-17 is 40% of what it was in FY 2009-10. The effective operating budget of the Coastal Restoration and Protection Authority has been cut by 60% over the last six years. The most common immediate response to this data is that the drop in revenue was caused by a drop in oil prices. Oil prices were undoubtedly a primary driver of the decrease in revenue for the coastal program, but the pattern of decline indicates another factor that has more ominous long-term implications for funding the CPRA budget.

From 2012 to 2014 there was a $5 million decrease in revenue even as oil prices climbed to over $100 per barrel in July of 2014. The other factor affecting revenue was a decrease in production caused by a decrease of drilling activity in what should have been an otherwise optimal economic environment for drilling.

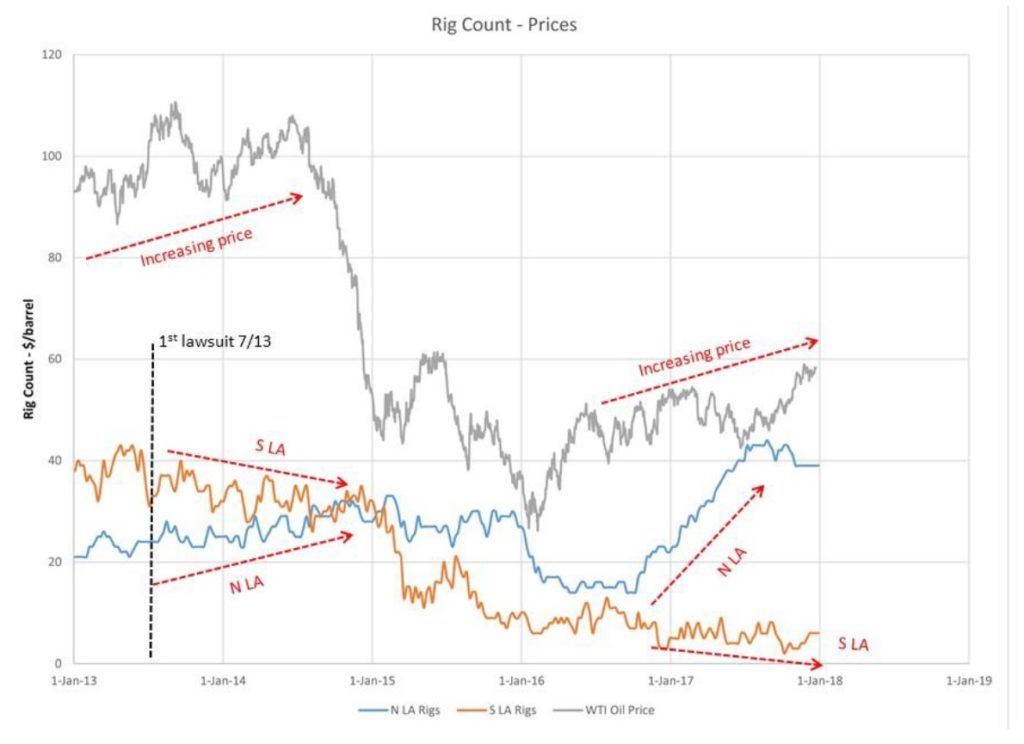

The drop in drilling activity in south Louisiana can be seen in the rig count data collected by the LA Dept of Natural Resources.

The south Louisiana rig count began dropping almost immediately after the filing of the first coastal lawsuit in July of 2013. By comparison the north Louisiana rig count reliably tracked the price of oil increasing throughout 2014. On one hand there is a clear response of the south Louisiana rig count to the drop in oil prices, on the other hand, the trend line of decreasing rig count after the lawsuits were filed has been relatively continuous throughout the changes in oil price. The real impact can be seen after oil prices began to rise in early 2016. North Louisiana and most of the rest of the country responded to increasing prices with increasing rig counts; south Louisiana continued to decline. It is true that the dramatic uptick in north Louisiana rigs is due primarily to activity in the Haynesville Shale, which is a resource play, but rig counts in conventional plays across most the country also increased over this time span.

What these data show is the effect of an exodus of oil and gas companies from south Louisiana due to the hostile business climate brought about by coastal litigation. The effects of legacy lawsuits on oil and gas industry drilling activity go back several years prior to the coastal lawsuits as shown in this study by Dr. David Dismukes of the LSU Center for Energy Studies. The real impact of companies leaving south Louisiana is not just the number companies, but the size of the organizations, and their potential for economic impact. It is worth noting that John Carmouche attacked Dr. Dismukes in what has been described as “character assassination” after the publication of this report. Dismukes may be willing to talk about this attack.

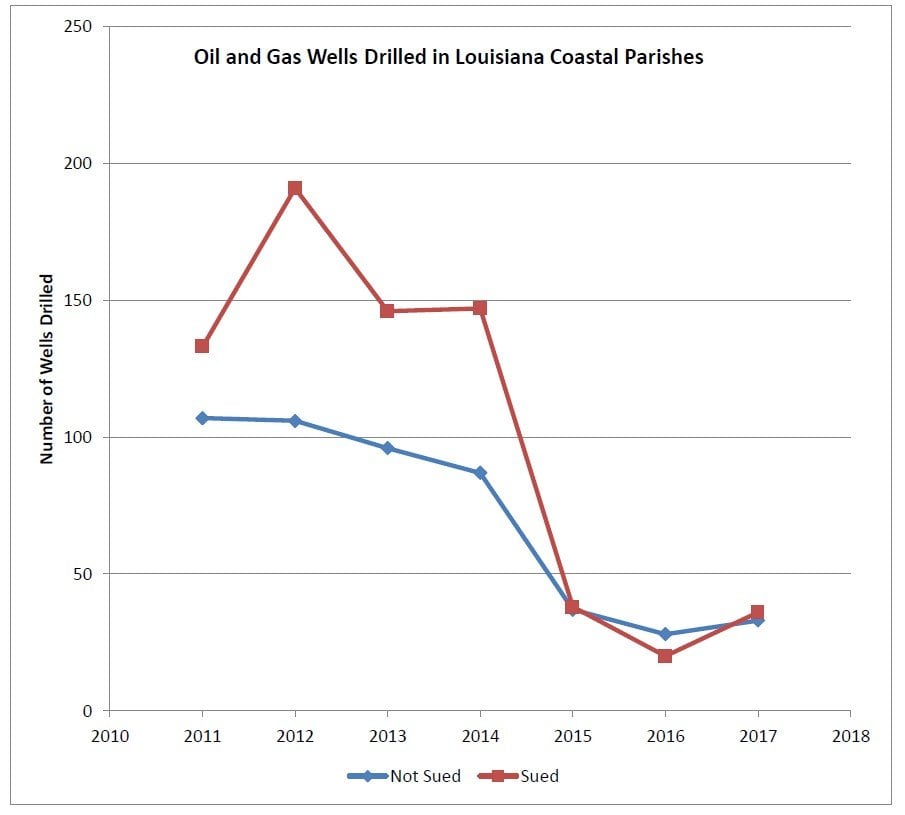

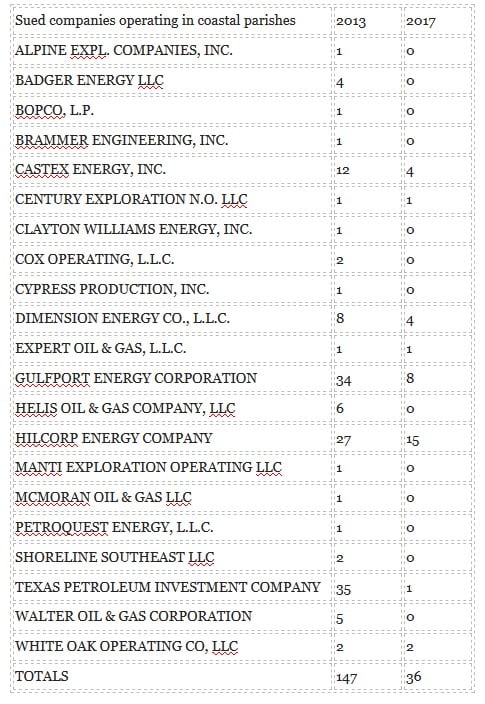

Data from the LA Dept. of Natural Resources on wells drilled in the coastal parishes of south Louisiana clearly shows that the drop in rig count after the filing of the coastal lawsuits was driven by a decrease in the number of wells drilled by companies that were named as defendants in the lawsuits. Those companies collectively drilled 191 wells in the coastal parishes in 2012. By 2016, that number had fallen to 20. The drop in the number of wells drilled by companies that were sued is disproportionately greater than the drop in companies that were not sued over the same time period. This unquestionably illustrates the impact of the litigation. What is more important is the character of the companies that have stopped drilling in south Louisiana. Two companies listed on the table on the next page that have ceased drilling operations in south Louisiana are worth noting. Badger Energy was founded by Paul Hillard in the 1950s. The company was active in south Louisiana up until the filing of the first coastal lawsuit. Hilliard and Badger have been an integral part of the Lafayette economy and in particular in support of philanthropic endeavors.

Helis Oil & Gas was founded in New Orleans in the 1930s. The company still occupies the same office on St. Charles St. that it started in. Over the years the Helis Company and the Helis Foundation have been vital supporters such things as the Sugar Bowl, the Fairgrounds Race Track, the WWII Museum, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the City Park Sculpture Garden and many others. The company is still actively drilling in Colorado and Wyoming, but it ceased all drilling operations in south Louisiana after the filing of the coastal lawsuits. The loss of participation of these types of companies in the economy of south Louisiana has ramifications far beyond the operating budget of CPRA. At some point companies like Badger and Helis may decide that it no longer make sense to have offices in south Louisiana. Louisiana routinely ranks in the top ten of the list of “judicial hellholes”. The hostile business environment created by coastal litigation reaches far beyond the economic impacts on the coastal restoration program.

Alternatives to Litigation

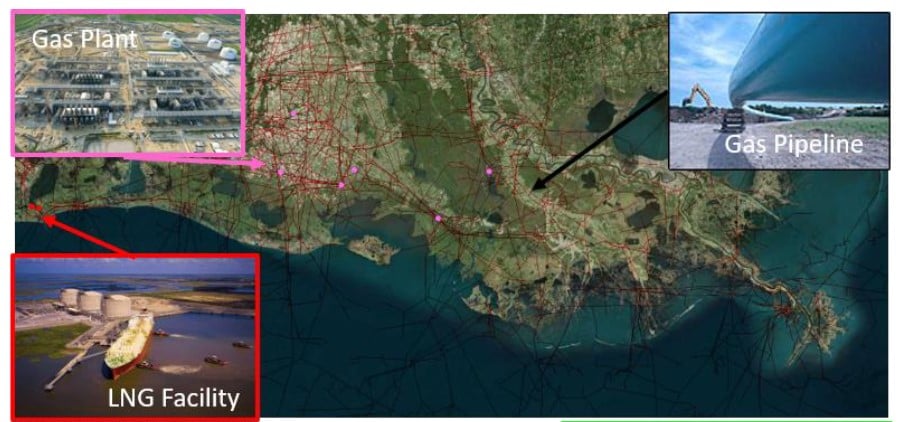

Any critical evaluation of a business enterprise would not be legitimate with providing an alternative to the processes being critiqued. The alternative to coastal litigation is cooperative engagement with the oil and gas industry. Although the number of companies conducting drilling operations in south Louisiana has been in steady decline since the first legacy lawsuits were filed, the operations of the transportation, storage, processing and refining components have been stable or growing. The port facilities at Venice and Fourchon are essential to all operations in the federal offshore. Growth in the Liquified Natural Gas processing and transportation holds great promise for the economic growth of the state. All of these components of the oil and gas industry are inextricably intertwined in the natural environment of the Louisiana coastal zone. The oil and gas industry has a vital and vested interest in insuring the long term sustainability of the coast.

The economic value of the hydrocarbon energy that flows through the infrastructure in the coastal parishes of Louisiana is issue of national security. A one-day interruption of this energy flow would devastate the American economy. The rest of America expects and demands that the oil and gas industry will maintain and sustain the infrastructure of oil and gas pipelines, gas storage facilities, gas processing plants, oil refineries and LNG facilities along the Louisiana coast. It is a false dichotomy to assume that this infrastructure can be sustained without also sustaining the natural ecosystems within which it is embedded. It is also important to understand that oil and gas companies are far and away the largest private landowners in the coastal zone. The two largest landowners, ConocoPhillips and Apache have property management staffs that work in the field every day to insure sustainability of the natural environment.

The future of the oil and gas industry’s involvement in coastal sustainability can be seen in projects like the Blue Hammock Bayou natural infrastructure pilot project. Working with The Nature Conservancy and CH2M (now Jacobs) Engineering Shell Pipeline devised a pilot project to test protecting a pipeline crossing by building natural marsh protection around it instead of tradition concrete, steel and rocks. As the report states:

“In a collaborative effort supported by CH2M scientists and coastal engineers, and Shell, ongoing monitoring and assessments of the Blue Hammock Bayou are being conducted. The findings indicate that the natural infrastructure approach is already performing beyond expectations, with strong plant growth and accumulation— rather than erosion—of sediments. The sustainable solution is protective of the pipeline, has helped stabilize the marsh, and has greatly enhanced the natural habitat.”

Similarly, oil and gas companies are involved in The Water Institute of Gulf’s Working Coast Strategy. Chevron, Shell and Danos are all participating in a project at Port Fourchon to use the dredged material derived from deepening the channel to port in a marsh creation project. Oil and gas industry geologists are also involved with the Louisiana Geological Survey in the development of the Coastal Geohazards Atlas. Construction of the atlas will rely heavily on the interpretation of geological faults from oil and gas industry seismic data. When completed, that atlas will be a valuable tool in coastal sustainability planning. CPRA announced last week that they plan to put together an expert panel on faulting.

The oil and gas industry is already moving towards developing the capabilities that would be required in a broad cooperative engagement with parish, state and federal agencies. The scope of this engagement and the magnitude of the projects in which the industry would be involved could be dramatically expanded in the absence of coastal litigation. Currently hundreds of millions of dollars are being wasted by oil and gas companies on legal defense to the litigation. This money could be employed much more effectively in pursuing long-term coastal sustainability working with the governmental agencies. It is time to support the business of coastal sustainability instead of the business of coastal litigation.

The research in this post is by a ValueWalk fan, a Geologist who has worked in the oil and gas industry in south Louisiana for 39 years.