Askeladden Capital letter for the first quarter ended March 31, 2018; titled, “The Asterisks.”

Dear Partners,

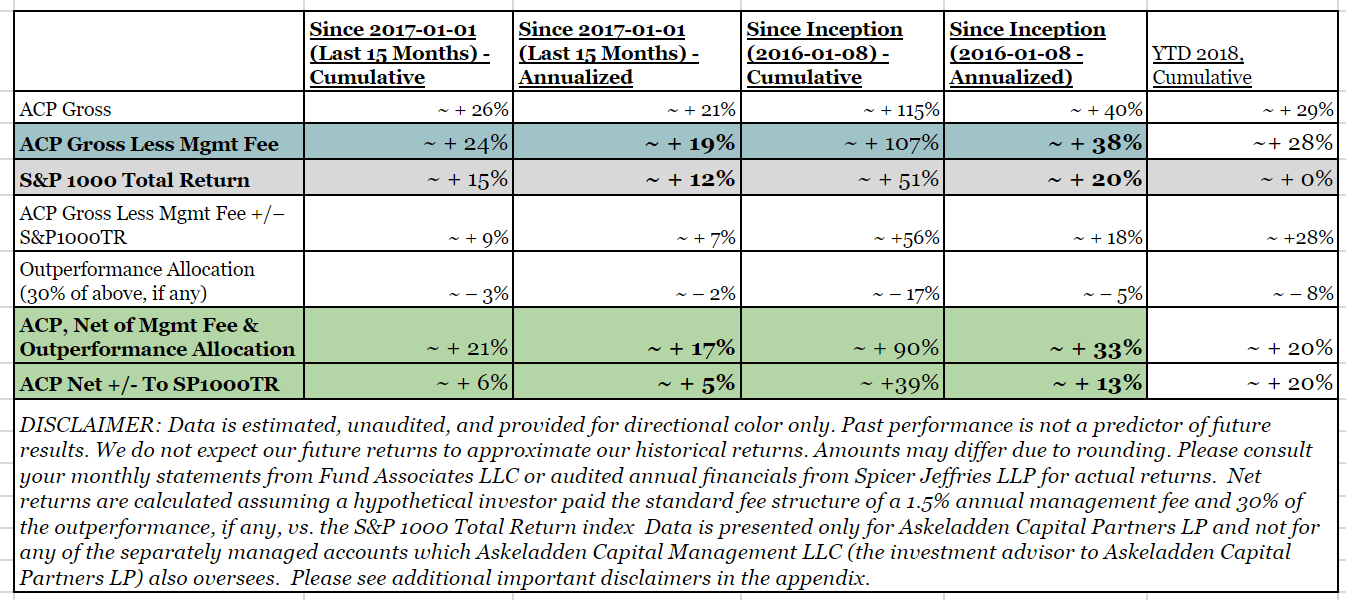

In my last letter, I noted that the early days of 2018 had been kind to our portfolio, more or less making up for a frustrating 2017 in which the market rallied without abandon, yet refused to recognize (or actively punished) good fundamentals at most of our portfolio companies. Here’s how we’re doing now. As always, please remember that we do not use leverage and typically maintain a double-digit cash balance.

As you can see, 2018 has continued to be profitable; our gross returns during Q1 were (approximately) + 28%, with strong results across the portfolio, ranging from a great earnings report at Franklin Covey to meaningful gains from our small bucket of oilfield technology products (currently ~610 bps aggregate exposure) to Fogo de Chao being bought out by a private equity firm. Conversely, the index finally did something other than go up and to the right. Instead, the S&P 1000 Total Return bounced around a lot, and ended up more or less flat to where it started.

For both 2018-specific and more general reasons, I’ve updated the presentation of our (unofficial) performance numbers in an effort to help investors focus on what I believe to be the most relevant evaluations. First of all, over the course of 2018, I’m going to focus my commentary (and your attention) on results since the beginning of 2017 rather than 2018, since I view a large percentage of our gains in early 2018 as simply “deferred” gains from 2017. While it’s always dangerous to have any near-term expectations for market performance, I certainly believe that our portfolio is, in aggregate, meaningfully undervalued, and that substantial additional value creation will occur over the course of the year for our portfolio in aggregate. Hopefully the market will continue to recognize both factors.

Second, more broadly, I’ve updated the table to break down the various contributors to the difference between gross and net performance, especially since we have a unique fee structure which only charges a performance allocation on outperformance vs. the index, if any, over a three year period.

The Asterisks.[i]

I recently reread Howard Marks’ The Most Important Thing (Illuminated), which was the book that started me on my value investing journey, and still (in my opinion) the most thoughtful and important book on the topic of value investing. (I also greatly enjoyed The Art of Value Investing and The Manual of Ideas.) One of the core ideas in The Most Important Thing is what Marks calls “second-level thinking” – seeking the deeper, more nuanced answers, rather than the easy but often incorrect ones.

Marks references this idea repeatedly – for example, he points out that it’s not possible to know with absolute certainty whether an investment was a good one even if it pans out.[ii] The takeaway here – one that I, of course, didn’t fully grasp when I was a hotshot young investor fresh off a great year or two in my PA (and on my way to a bad one!) – is that the best time to “rub your nose in your mistakes,” to use a Mungerism, isn’t only when you’ve made a lot of mistakes.

In fact, perhaps the best time is when you haven’t made many egregious ones that you can see, and need to remain focused on preparing for all environments. These aren’t “mistakes” so much as what I’ll call “asterisks” – i.e. the “yeah, but” factors. The almost-bottlenecks.

That’s where I find myself today. Although not every position has delivered expected returns, and not every fundamental expectation I have had has materialized, nobody (even Buffett) gets everything right all the time – and in aggregate, evaluating my performance over the past few years, I feel quite confident that I’m doing well.

The immediate corollary to that is that there are always things I can do better. This is not merely theoretical, aw-shucks humility: to put it in Lean manufacturing terms, “continuous improvement” is one of my core frameworks.

It’s easy to say and harder to practice, because it requires setting ego aside and adopting a growth mindset – i.e., disassociating identity from actions enough to allow yourself to change maladaptive actions without changing your identity. How hard is that? Really hard – a little while back, I had a conversation with a brilliant young aspiring investor who, entirely unironically, emphatically told me that his worldview was sacrosanct and he only had interest in learning things and improving in ways that didn’t conflict with his existing worldview.

Most people usually have enough social awareness to not say things like that out loud, but the truth is we all believe it, to one degree or another. Every time we downplay our own mistakes of equal or lesser severity to those for which we castigate others, every time we tune out when someone says something we don’t want to hear: that’s intellectual dishonesty, whether we like it or not.

And that’s the worst thing any investor can do: lull themselves into a false sense of complacency by highlighting their victories while sweeping everything else behind the bookcase. So, yeah, I’m proud of what I’ve accomplished since launching ACP. But in the spirit of the season, as some of my Bible Belt friends would say: “pride comes before a fall.” With that in mind, here are five “asterisks” affecting our performance since inception and our near future.

As usual, sharing these is somewhat counterintuitive, since most investment managers try to focus on what they’re doing well rather than what they’re not. But I’m hopeful that you will understand that I’m coming from a place of wanting to do the best job I can, and that requires not glossing over the “bad stuff.”

--

(1) The new tax policy.

I’m starting with this one because it’s the easiest to quantify. (Somewhere, Richard Feynman is rolling over in his grave.) Most of you are likely aware that the U.S. government reduced the statutory corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%. There are various other provisions such as interest deductibility that are worth considering, but overall, it’s still a meaningful benefit to U.S. companies.

How big of a benefit? Well, that depends: many global multinationals already pay tax rates close to or lower than the current U.S. statutory rate; a few years ago, you may remember that a big stink was raised about companies like Apple and Google using low-tax domains like Ireland to shelter their global profits. On the other hand, companies that generate all of their profit in the United States – such as Franklin Covey – could see their tax bill drop like a rock, boosting after-tax cash flow by 20%+.

There are mitigating factors here; for example, in price-competitive, commoditized industries, much of the benefit from lower taxes might be passed along to consumers or employees or others in the value chain. Moreover, many companies may choose to reallocate some of the newfound profits to corporate initiatives. However, for most of the companies we own or follow, we do expect a benefit large enough to be analytically meaningful. Of the 100+ companies on our watchlist, a quick review suggests that the average benefit is around 10% for the ~40 I’ve applied new valuations to so far.

This is a very unscientific number: it depends on my underwriting as well as the specific sample of companies that I’ve had time to work on; in many cases, the analysis may not have been particularly thorough, just a “best guess” based on previous knowledge to update the watchlist valuation until a deeper dive was appropriate. Nonetheless, 10% seems to roughly align with the benefit that a few of my other investor friends have seen in aggregate.

It seems obvious that this is a one-time benefit to performance that does not whatsoever imply any degree of investment skill. The first question is whether I should view it as an offset to our absolute performance, relative performance, or both. I think the answer is “both,” although to different degrees – I do think our specific set of companies is a little more benefited than our index overall because I tend (for whatever reason) to skew towards smaller, primarily-domestic stuff. So, on the basis of nothing but gut feel, let’s say that it benefited our index ~10% and ACP ~12 – 13% or so.

Second, and more interestingly: when should we “penalize” our mental accounting of these gains? You could argue for assigning it all to 2018, since the bill wasn’t signed until Christmas-ish – but the index has actually gone down since then. (Buy the rumor, sell the news?) It seems much of the rally in 2017 was related to expectations of lower taxes… but then too, perhaps was much of the rally in late 2016 after the election.

Simultaneously, though, many of our companies have seen little to no benefit in their market price based on the new tax rates – Franklin Covey (FC), for example, is still meaningfully undervalued on the basis of old tax rates, let alone new ones; meanwhile, I haven’t meaningfully updated my valuation (and, seemingly, neither has the market) for companies like Liquidity Services (LQDT) and Aspen Aerogels (ASPN) that are not currently generating material free cash flow. So in some cases like these, the benefit may accrue to some future period – 2018 or beyond.

Wherever one chooses to assign it, I do believe it’s worth mentally separating some portion – around twelve percentage points for ACP and ten for the market, perhaps – of our gains over the course of 2016, 2017, 2018 as one-time and non-recurring.

(2) Tax efficiency.

More on taxes. (It is tax season, after all.) One benefit of long-term investing, whether in the index or an individual securities, is that it is tax-advantaged: the way compounding works, you get a benefit from paying taxes less frequently than more frequently.

For example, assume that you invest $100 to earn a 10% annualized return, with a 20% capital gains rate, over the course of ten years, paying taxes at the end of every year. If my rough dumb spreadsheet model is right, you’ll end up with ~$216, equating to an 8% annualized return. (Easy enough – you earn 10% per year, then pay 20% of that 10% in taxes, and are free to reinvest the earned 8%. Rinse and repeat.)

On the other hand, if you invest $100 and earn 10% annualized for ten years while paying no taxes, you’ll end up with $259. You still owe ~$32 worth of taxes, but even if you decide to cash in at that time, you’ll end up with $227, representing an ~8.6% annualized return. In other words, you boosted your return by 60 basis points annually over ten years. Nothing to sneeze at.

This gets more important at higher levels of returns – i.e. if you can compound at 15% per year for a decade under the scenario described above, the “tax every year” gets you 12% after-tax compounding, while the “tax at end” gets you 13.1%. Of course, it’s very difficult to find things that will compound at 15% for ten years, and much easier (though still not easy) to find things that will compound at 15% for a few years.

Even more important, of course, is receiving long-term capital gains treatment rather than ordinary income treatment. Investment managers are typically evaluated on their “investment skill” (i.e. pre-tax return vs. the index), but excluding tax-sheltered investors like charities or IRAs, most investors don’t get to buy an enchilada with “investment skill.” They have to pay for it with after-tax dollars.

Unfortunately, ACP has not, to date, been particularly tax efficient. For a variety of reasons, from inception through the end of February 2018, ~70% of our total income was recognized as short-term capital gains. Some of this falls in the “high-class problem” bucket – we were up ~69% gross in 2016, largely due to the market revaluing our portfolio companies in an abnormally rapid timeframe. When you have a meaningfully sized position in a stock at $12 that you think is worth $15 or more, you’re not just going to sit there if it gets to $15+ in short order.

This is not totally hypothetical – while the numbers are directional, we went down that path twice with Fogo de Chao since the summer of ’16. The first time, it didn’t seem reasonable to sit on a position that was trading at or above my estimate of fair value to wait for long-term gains treatment – and it turned out to be a good decision, as the stock more or less round-tripped. (The second time, it was bought out, so I didn’t have an option.)

I’ve thought about tax efficiency before, but set it aside for what I still view as a good reason: making investing decisions in the face of uncertainty is difficult enough when you’re just focused on a stock’s price relative to its value, and relative to the rest of your portfolio and opportunity set. Adding in the variable of “well, if I hold on for five more months…” makes the decision, in my estimate, somewhat muddy, and I don’t want to let the tax tail wag the investing dog. (I’ve heard lots of horror stories about year-end tax-loss selling leading to major lost gains.)

Part of this is related to the environment: as early 2018 has demonstrated, we will not always be in an environment where the market does nothing but go up and to the right, which would ease some of the “burden” of owning something and seeing it go up 30% in six months. (Again, high-class problem.) That said, I’ve also realized – particularly because I’m an investor in ACP and I don’t want my gains eroded by taxes – that I can’t just pretend the issue doesn’t exist.

I still don’t think that evaluating long-term vs. short-term gains when the “deadline” is far out makes a lot of sense. Moreover, some of the issue is self-resolving, and I would anticipate 2018 and beyond to be much more weighted toward long-term capital gains. At the same time, I do think that I can take structural steps from a portfolio management perspective to help alleviate these challenges. This is still very much a work in progress (i.e., it is something more in the “question” than “answer” stage), but here are some initial steps:

- A (directionally) more diversified portfolio where each name isn’t maxing out its “risk limit.” Setting aside the important but separate topic of how I think about that number, let’s just say that for some company, I don’t want it to be more than 9 – 10% of the portfolio.Well, if the position is at 9%, and then the position goes up 30%, independent of anything else, I’m going to want to sell some, because it would be illogical to believe it merited being at the maximum position size at a great valuation, and is now at the same or bigger size at a fair valuation.On the flip side, if the position was sized at, say, 6 – 7% initially, then there wouldn’t be as much pressure to sell as many shares, as fast, and I’d be more willing to let the position play out.Don’t worry, I’m never going to own 50 stocks, or probably even 20 – but at the same time, owning fewer than 10 was never my It just happened, based on the opportunity set available to me. As I’ve continued to build our watchlist, and developed competencies in new areas, there are more businesses I feel comfortable underwriting, and statistically, more businesses at any given time that will meet our investment criteria. For me, having a low double digit number of positions seems like the “sweet spot.”

- A (directionally) higher focus on businesses that have a lot of opportunity to create value, rather than “businesses with a price.” I hate using reductionistic “growth” vs “value” terminology, but directionally, you can think of our portfolio generally containing two kinds of positions.The first is comprised of businesses that are not phenomenal, but are “good enough,” and are trading at valuations that don’t imply very much execution at all. Going back to my equation of returns, R = Y + G +/– M, where Y = free cash flow, G = growth in free cash flow, and M = valuation multiple. these “businesses with a price” will, over our holding period, have the majority of their return driven by Y and M. As such, if M moves up, Y necessarily moves down, and it’s hard to justify maintaining the investment.The second category is comprised of businesses that have more value creation opportunities, whether due to growth potential, meaningful margin improvement potential, or a combination of both. These tend to be better businesses on a forward-looking basis, although not perhaps “great businesses” the way people normally categorize them, but rather perhaps what people will look back in 5 or 10 years and retrospectively call a “great business.” Here, the growth component “G” will likely amount for a higher percentage of returns than Y or M.Over time, I’ve followed the path that many value investors do: at first, I clung to the quantitative security of the Y and M, which seem to be tangibly present in the “here and now,” vs. the somewhat murkier, harder-to-predict “G” off in the distance, which might materialize or might just be another illusion of water in a dry, dry desert.

What I’ve realized is that, with limits and under specific circumstances, it’s not foolhardy to attempt to underwrite the future with a reasonable margin of safety, and every investment requires doing so. In fact, oftentimes, low-multiple “value” ideas are just underwriting the inverse of some growth thesis. For example, a few years ago, I’d looked at Viacom, the owner of a lot of old-school channels like MTV – and given a fixed pie of consumer time for entertainment, the bull thesis on Viacom (i.e., that its brands would remain relevant) required underwriting something that, if flipped on its head, was basically a bear thesis on the “new kids on the block” like YouTube.

That’s obviously a very reductionistic/simplified version of the thinking, but I’ve come to realize that in certain circumstances, underwriting a strong business in a strong market continuing to grow and accretively allocate cash flow can actually be easier (not to mention more profitable) than figuring out whether some dying business will die more or less slowly.

Concomitantly, this approach leads to better tax treatment and less frequent taxation. With Franklin Covey, for example, there’s a credible chance that it could compound at 15% for a decade. Even if that turns out not to be the case, relative to a company like Korn Ferry (KFY) that we owned because it was a good-enough business at a stupidly cheap price, Franklin Covey delivers the opportunity to compound at a high rate for a much longer period of time.

Of course, it would be stupid to ignore cheap businesses staring us in the face, and it’s also important to be cognizant, as Marks points out in The Most Important Thing, that just because we want some sort of return out of some class of investment doesn’t mean the world cares a bit about providing it to us. Still, I’ve been shifting my emphasis (in terms of new research) toward better businesses for a while now, and in combination with item (a) above about portfolio construction, I think this should reduce portfolio turnover without dampening return potential.

(3) Scaling (Trading, Positions).

I haven’t reviewed the empirics recently, but I believe it’s a fairly well-known and well-documented trend that funds tend to perform more poorly as they get bigger. This is a multicausal phenomenon and there are certainly a large number of contributing factors, but one of the major ones is simply that it’s harder to invest a billion dollars than a million dollars. Buffett, who would be happy to compound behemoth Berkshire at low double digits, once said that he’d compound at 50% per year if he was managing a pool of capital on the order of the size of ACM… that seems like an unrealistic target to me, but directionally, the point is that opportunities at scale get much more sparse because there’s a lot more competition.

I’ve aimed to partially solve this problem structurally by capping ACM (including both ACP and separately-managed accounts) to $50 million in fee-paying AUM (i.e., excluding my own and my parents’ very modest capital.) Notwithstanding that, managing that sort of portfolio would be meaningfully different than managing the amount that we are currently managing, in at least two key ways.

(a) For some positions, position size would become constrained by float, liquidity, or other factors. Many of our most profitable positions have been thinly-traded micro-caps; even some of the “larger” small-caps like Fogo de Chao had limited float and trading volume thanks to high insider ownership or similar factors. Most of these positions can continue to be meaningful and profitable for us well above $100MM in AUM, but it remains important to continue to build the watchlist – including with some larger, more liquid names – to give us the best statistical shot on goal of having plenty of opportunities.

(b) I suck at trading. I really do. A while back, one of our separately managed account clients noticed and called me out on this, for which I’m extremely grateful, as it likely meaningfully reduced the drag we experience on transactions. Nonetheless, as we scale, I’ll no longer be able to make a decision and, more or less immediately, have it reflected in the portfolio. As with tax efficiency, I certainly don’t claim to have “solved” this issue, but it’s something that I try to discuss with experienced fund managers running far more AUM, so I can at least avoid mistakes they’ve made and have some best practices to follow.

(4) A limited sweet spot.

You get a break… this is a short one. There are entire swaths of the economy that I willfully ignore for various reasons (for example, healthcare has too much potentially politically-volatile regulatory involvement for me to feel comfortable underwriting anything, and mining just tends to be a bad business.) That is sensible. However, there are also plenty of types of companies – for example, aerospace suppliers and paint vendors – that are perfectly reasonable to invest in and perfectly understandable (to me), yet historically have not fallen within my purview.

I’ve gotten lucky in finding a lot of opportunities over the past few years in my “sweet spot” of business services, light industrials with niche products, and so on – but there are also lots of great opportunities I’ve seen (in retrospect) that I either didn’t analyze because I didn’t know enough to do so (Aercap in early 2016), or analyzed and passed on because I didn’t have the toolkit to look at it the right way (KMG Chemicals). I certainly have no intentions whatsoever of looking for “hard problems” to solve – I’m firmly in the camp of wanting to jump over a one-foot hurdle by finding gaps between value and price wide enough to drive a semi-truck through – but as one of my mentors used to say, value isn’t always dressed like a 0.3 ounce red jellybean.

It’s easy/comfortable to continue only working on the kinds of companies I’m already familiar with, but given how knowledge compounds over time, it’s important to build an understanding of different industries and kinds of situations, so that a few years down the line, they too can become sweet spots (if possible). So I’m making an effort to study new industries and stretch my comfort zone by engaging in new types of research.

- Macroeconomic stability / no “bad luck.”

The world can be split into two types of people[iii]: those who attempt to reason from first principles with little regard for how things are done (Ayn Rand, Peter Thiel), and those who don’t care about first principles and simply accept “well, that’s the way things are” (seemingly, most adults I knew growing up.) This is obviously a broad-brush categorization, but bear with me.

One surprisingly-great book that is surprisingly-rarely cited (at least among people I know) is Jerome Groopman’s How Doctors Think, a highly engaging yet very thoughtful discussion of how cognitive biases affect doctors’ diagnosis and treatment of patients. I’ve read it thrice. Groopman interviews a lot of great MDs, but one of my favorites (for a lot of reasons) was a cardiologist named James Lock. Lock, after coming up with a great medical theory for a certain condition that made perfect sense, found out that it didn’t work in the real world. Discussing what went wrong, around pages 148 – 149, Groopman quotes Lock:

“My mistake was that I reasoned from first principles when there was no prior experience. I turned out to be wrong because there are variables that you can’t factor in until you actually do it.”

While doctors and CEOs might have a nice debate over whether biological or business systems are more complex, what Lock describes certainly happens a lot in investing.

Take the example of Mistras (MG) and Team (TISI), two companies I’ve followed (never owned) that provide “nondestructive testing” services for refineries and other kinds of clients. Oversimplifying again, their job is to use tools ranging in sophistication from “bang on it with a hammer” to ultrasound/electromagnetic testing figure out what parts of the plant need maintenance. You would think that this is a relatively stable business: after all, when you run a bunch of corrosive stuff through your plant at really high temperature and pressure, your plant tends to accumulate some wear and tear, and both safety and economics would seem to dictate. Indeed, the historical record tended to reflect that: these businesses saw stability and growth despite plenty of macroeconomic challenges.

And then, over the last few years, that thesis broke, and (honestly) nobody I’ve talked to or heard from really has a good explanation of why. I mean, there’s a first-level explanation about capex budgets and crack spreads that makes sense. But it doesn’t explain, on the second level, why this time has been different: why, for four or five turnaround seasons in a row, everyone in the industry has thought “this spring was weak, but it’ll come back in fall…”

There was a point where I was actually considering taking a small position in Team (TISI). I didn’t, mostly because I was uncomfortable with their debt load, but I might have set aside those concerns if the price had dropped another few dollars. There was a clear and reasonable case to be made for the stock being a good risk-reward – and I, in fact, made it (to myself, in my research document.)

Not all that much longer thereafter, Team announced a quarter from hell (there’s really no other way to describe it) and was forced to conduct a very large, dilutive financing that permanently impaired pre-financing shareholders. The position, if I had taken it, would have resulted in significant losses – not necessarily for the portfolio overall (given that it would have been a small position), but certainly not trivial either.

Would investing in Team have been a mistake? Again, it’s not that simple. If someone offers you $1,000 if a coin comes up heads and you have to pay $100 if it comes up tails, it’s a good idea (statistically) to take that bet. Assuming you have spare cash and the person is willing to play for a while, you should, in fact, keep playing – even if the first five coins come up tails and you’re $500 in the hole. (This is perhaps a poor example because of the gambler’s fallacy, and because I don’t gamble, but real-world odds are never this much in your favor.)

What is clear, however, is that the only way to make better decisions is to keep track of the ones you make, and what the consequences are – and to be thoughtful and humble about whether good results (or avoided bad results) are a function of luck or skill.

So far, I’ve managed to avoid Team-like situations. But at least some portion of that is simply luck, not skill. The truth is that when it comes to these sort of things, most people don’t really see it coming. Plenty of smart investors were blindsided by the oil price crash. Plenty of restaurant executives were befuddled by the sudden demand pocket in a generally robust consumer environment. It remains important to focus on not just what does or did happen, but what could happen.

That’s why, for example, despite temptations to build the positions further, I kept myself in check when investing in three promising oilfield technology companies. Even if the completions market isn’t too robust, their technology should allow them to gain share and deliver strong cash flow – but I’ve also seen the market fall apart pretty much overnight before, and while a repetition seems unlikely in the near term, unlikely doesn’t mean impossible. It means that if I take on some risk there, which there’s no way around, I should be extra-careful about where else I’m taking on risk. There’s no such thing as risk-free investing, but there is such a thing as bearing risk smartly, and not getting complacent because recent results have been solid for us and the market in general

--

That is certainly not a complete discussion of the things I could get better at. It is, however, what is top of mind. When the world isn’t rewarding us for good behavior, sometimes it’s a good idea to eat some ice cream and pat myself on the back. When the world is rewarding us, I feel it’s important to step back and remember that circumstances may not always be as conducive – and, armed with that knowledge, take the right steps to maximize our chances of success.

Thank you as always for your continued support. While it is extremely unlikely that future returns will even come close to approximating results since inception, I remain confident that a process based on thoughtful analysis and continuous improvement will continue to deliver results over the long-term.

Westward on,

Samir

Appendix

DISCLAIMER: Data is estimated, unaudited, and provided for directional color only. Past performance is not a predictor of future results. We do not expect our future returns to approximate our historical returns. Amounts may differ due to rounding. Please consult your monthly statements from Fund Associates LLC or audited annual financials from Spicer Jeffries LLP for actual returns. Decimal points have been excluded so as not to convey a level of precision that these estimates are not intended to convey. Net returns are calculated assuming a hypothetical investor paid the standard fee structure of a 1.5% annual management fee and 30% of the outperformance, if any, vs. the S&P 1000 Total Return index, which was chosen because it has historically outperformed the Russell 2000 and most accurately represents our typical investment universe of small and mid-capitalization U.S. equities (i.e., those with a market cap of $10 billion or less). We may invest outside this universe (for example, in U.S. large caps or international small caps.) Individual investors' returns may differ from those presented here due to their date of entry into the fund or their specific fee structure (for example, accredited but non-qualified clients may not, by law, be charged a performance allocation, so they are typically charged a higher, flat management fee). Results are presented only for Askeladden Capital Partners LP and not for any of the separately managed accounts which Askeladden Capital Management LLC (the investment advisor to Askeladden Capital Partners LP) also oversees. While separately managed accouts are generally allocated very similarly to the fund, SMA clients' performance may differ based on factors such as: timing of account opening, tax considerations, specific client instructions, and manager discretion; therefore, SMA clients should consult their Interactive Brokers statements for specific performance information for their account. This is not an offering of securities or solicitation thereof; any offering of securities would only be made to accredited investors via a Private Placement Memorandum under Rule 506(c) of Regulation D, and any prospective partners who did not have a pre-existing relationship with Askeladden as of 1/18/2017 would be required to verify their accredited status with relevant documentation. This requirement does not apply to separately managed accounts. Any documents prepared prior to 2017-01-18 were not intended for public distribution and should be read accordingly. Askeladden Capital Partners, and SMAs that mirror its strategy, should be considered high-risk investments suitable for only a small portion of an investor's overall portfolio, as they involve the risk of loss, including total loss. Specific risk factors are enumerated in our Form ADV.

[i] I too thought that this would make a good band name, and Google seems to imply it’s already been done – maybe twice. [ii] If this seems contradictory, the brief summary is that if you buy a stock and it goes up and to the right, all that tells you is that it went up and to the right – it doesn’t tell you anything about why what happened happened, or what else could have happened if some different set of circumstances had arisen.

This is one of the reasons I choose to focus, at least in the near term, more on fundamental developments at our portfolio companies rather than mark-to-market prices: assuming that I don’t make any egregious errors in evaluating a business and determining what sort of valuation would be appropriate given some set of fundamentals, then investment performance will follow over time from fundamentals that are nearby or better than what I underwrote when I initiated the investment.

[iii] The world is actually composed of 10 types of people: those who try to categorize everyone into a binary framework, and those who don’t.