(Due to President’s Day, the next report will be published on February 26.)

Italy will hold elections on March 4, 2018. Given that recent elections in the Eurozone have run an emotional gamut, it is difficult to predict the outcome. There was great fear before last year’s elections in France that a National Front victory could undermine the Eurozone. The National Front is a nationalist, right-wing Eurosceptic populist party. In light of surprise populist victories around the world,1 there were worries that France would be the next major win for populism. Emmanuel Macron’s surprising landslide put those fears to rest. On the other hand, there was little concern surrounding last autumn’s elections in Germany as Angela Merkel was expected to win easily. However, mainstream parties in Germany saw their popularity decline, offset by surprising strength for the AfD party, an anti-immigrant and Eurosceptic party. Since winning the election, Chancellor Merkel has struggled to build a ruling coalition. She recently made a deal with the Social Democrats (SDP) to form another “Grand Coalition” government, but in the process she was forced to give the SDP key ministries that will likely provide Germany more flexibility in managing the fiscal rules of the EU but will make the conservatives less likely to support this government for an extended period.

Thus, expectations for the French elections proved to be too pessimistic, while expectations for the German elections were overly sanguine. It appears the anticipated outcome for the upcoming Italian elections is similar to that of Germany; although there is clear evidence that populist parties are growing in popularity in Italy, predictions call for a hung parliament and the eventual creation of a center-right coalition that will not threaten the stability of the Eurozone. This sentiment is evident in the financial markets.

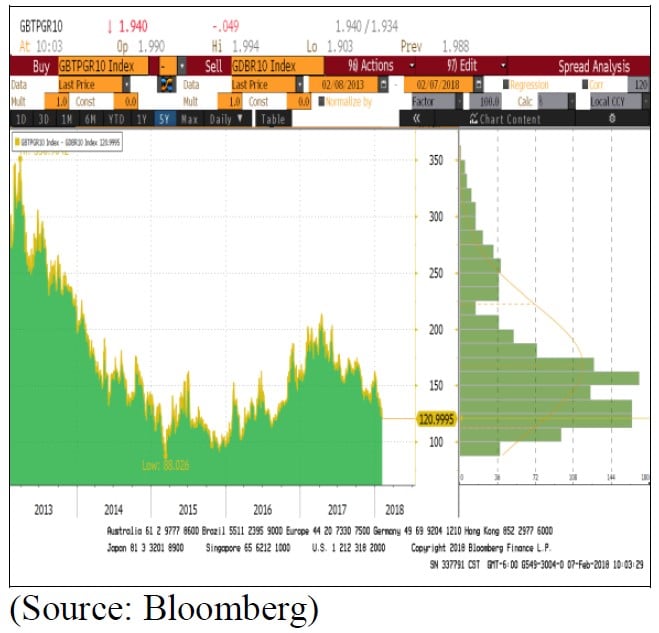

This chart shows the spread between Italian and German 10-year sovereign yields. Although German yields declined relative to Italian yields into early 2017, the spread has steadily narrowed since April 2017 to the present. If there were serious concerns about the Italian elections leading to Italy’s exit from the Eurozone, Italian yields would be rising relative to German yields.

Although we think the consensus case is the most likely outcome, there is potential for a negative surprise. Given that Euroscepticism is high in Italy, even a consensus outcome may not be all that favorable.

In Part I of this report, we will begin with the basic geopolitics of Italy with a focus on the natural divisions in the country that make it difficult to govern. From there, we will examine the political economy of Italy, especially how Italian political leaders managed the economy to deal with the sharp divisions between the north and south. In Part II, using this background, we will analyze the polling for this election and the potential outcomes. We will also touch on the issue of German influence in the EU. As always, we will conclude with potential market ramifications.

The Geopolitics of Italy

Italy has a storied history. The Roman Empire dominated Europe, the Middle East and North Africa for over four centuries and remnants of the Empire survived into the 15th century. Rome’s dominance was due in part to its geography. The Italian peninsula juts far into the Mediterranean Sea; whoever controls Italy will have extensive influence on that body of water and, consequently, parts of three continents. At the same time, the peninsula is vulnerable to seaborne enemies on multiple sides. Thus, part of Rome’s moves to dominate the Mediterranean Sea were to address its vulnerability.

Modern Italy has two significant geographic features. First, its northern border is set by the Alps. Second, the northern parts of the peninsula are partly isolated by the Apennines.

Northern Italy is industrialized and includes major cities such as Milan and Turin. The Po River valley is a key waterway that connects numerous cities in northern Italy and is one of the wealthiest parts of Europe. Southern Italy is arid and mostly agricultural; it is much less affluent. In 2015, Northwest Italy’s per capita GDP was €33.4k compared to the islands and southern Italy at €17.8k.2 These deep divisions are nothing new. Metternich, the Chancellor of the Austrian Empire for most of the first half of the 1800s, described Italy as “only a geographic expression.” One of the only institutions that was thought to be able to unify Italy was the Roman Catholic Church. However, Machiavelli noted in the 16th century that the church was “too weak to unify Italy, but too strong to let it happen.”

Various groups tried to create a unified Italy during the 19th century. Before unification, Italy was dominated by foreign powers.

This map shows the divisions of Italy in the early 1800s. The south (the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies) was under Spanish control,

while the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia was Austrian and the Kingdom of Piedmont- Sardinia was French.

Italian unification (the Risorgimento) began in 1815 and was fully completed by 1871. Various wars and movements emerged over this 56-year time span. Italy was difficult to unify due, in part, to its geography. For much of its history, Italian governments were dominated by northerners. However, the aforementioned economic divergences between the north and south also made it difficult to govern.

During WWI, although Italy was a member of the Triple Alliance with the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires, it did not join the Axis powers once the conflict began. Italy viewed the pact as defensive in nature and saw Axis actions as offensive. Italy fought on the side of the Allies with modest results. It was part of the “big four” at the Treaty of Versailles, with France, Britain, and the U.S., but most of Italy’s demands were ignored by the major powers. The lack of gains in the post-war agreements and the costs of the war hurt the Italian economy. In 1922, Benito Mussolini rose to power.

Mussolini used nationalism and imperialism in an attempt to overcome the aforementioned natural divisions in Italy. Through military action and treaty arrangements, Mussolini gained Libya, Tunisia, part of Egypt, Ethiopia, Somaliland and parts of the Adriatic Coast. However, the empire was lost after Italy’s defeat in WWII.

The Political Economy of Italy

Although devastated by the war, Italy’s influence on the Mediterranean and its importance to southern Europe led the U.S. to direct $1.5 bn in Marshall Plan aid to the country. Although that stream of funds ended in 1952, renewed support came from the Korean War as the U.S. imported goods from Italy. Italy was also one of the founding members of the European Common Market, the forerunner of the EU.

Like many of the European nations, Italy recovered strongly in the postwar period. The U.S. was determined to prevent the spread of communism and was generous in supporting the countries of Western Europe, of which Italy was a prime beneficiary.

However, even robust growth could not offset Italy’s geographic divisions. The industrial north’s economy clearly outpaced the south and internal migration could not completely equalize the difference. Italy was plagued with political instability. In the postwar period, Italy has had 65 governments, roughly one every 13 months. The inability of governments to remain in power is due, in part, to the geographic differences.

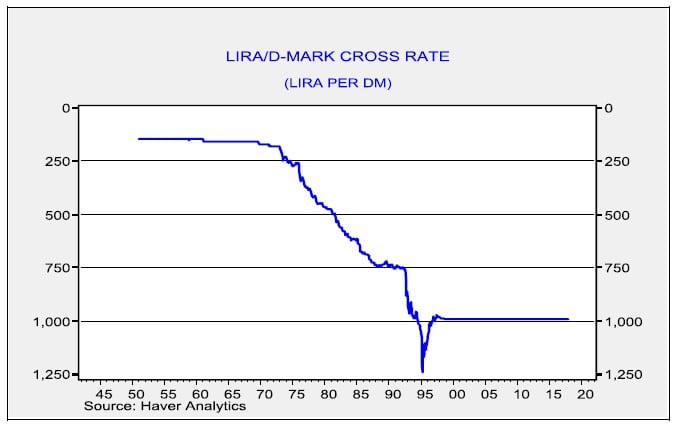

To offset the aforementioned geographic divisions, Italy ran persistent fiscal deficits and allowed its currency, the lira, to steadily depreciate. The chart below shows the lira/D-mark exchange rate. During the Bretton Woods period, the lira started declining against the German currency. After currencies floated in the early 1970s, the depreciation accelerated. However, note that once the Eurozone was formalized, Italy lost its ability to use depreciation as a tool to offset its lack of competitiveness.

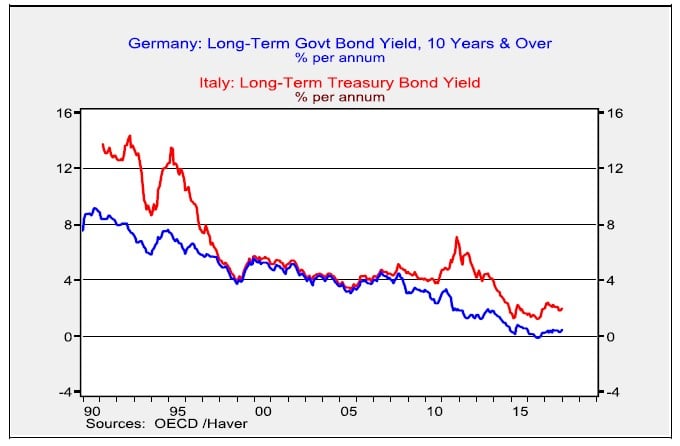

In general, the cost of steady depreciation is higher inflation. Investors, fully aware of Italian exchange rates and fiscal policies, would demand higher interest rates on Italian bonds. Of course, one of the benefits of joining the Eurozone was lower bond

yields.

Until the 2008 Financial Crisis, investors treated Eurozone sovereign debt as if it had equal risk on the assumption that Germany would not allow another Eurozone nation to default. The subsequent European financial crises have clearly shown that assumption to be false. And so, Italian bonds still trade at a premium to German bonds, although that spread has narrowed recently (as shown in an earlier chart).

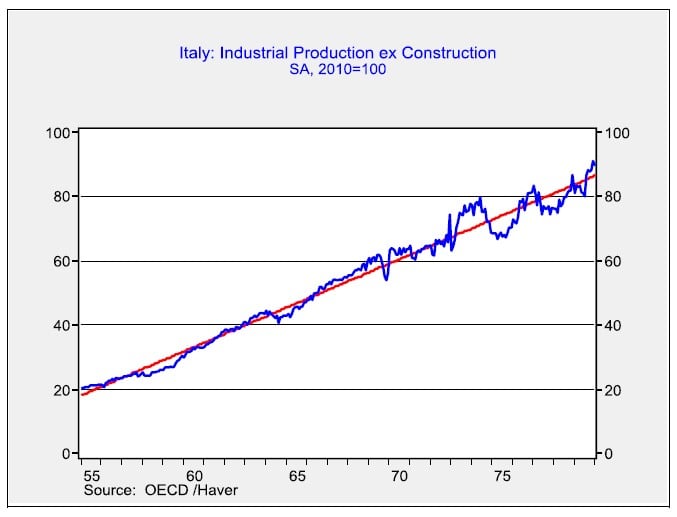

Joining the Eurozone has not improved Italy’s economic performance.

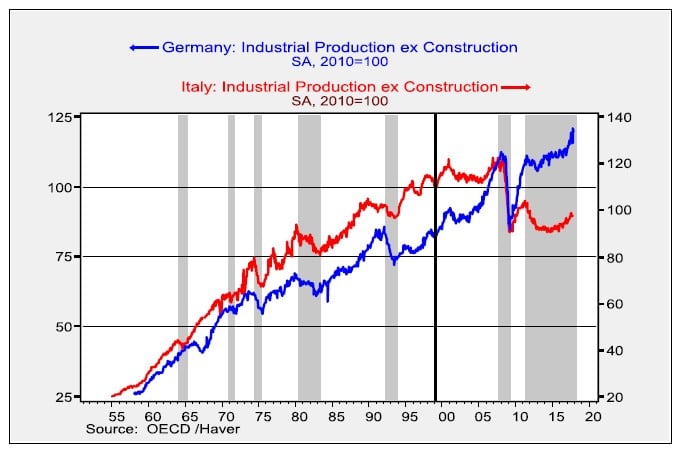

This chart expands the earlier industrial production chart, and added German industrial production. The shaded areas show Italy’s recessions. It is clear that Germany’s industrial output has been rising faster than Italy’s since the introduction o

the single currency. Perhaps even more astounding is that Italy entered recession in April 2011 and is still probably in a downturn even with the recent lift in growth.

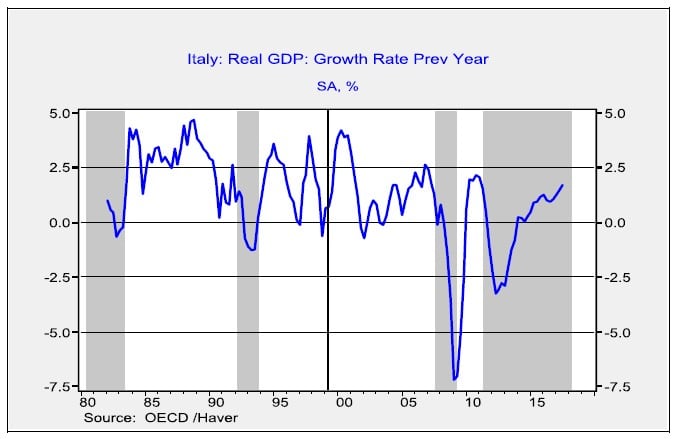

Essentially, joining the Eurozone undermined Italy’s economic model. Fixing the exchange rate to its Eurozone partners and the restrictions on fiscal spending have hampered Italy’s economic growth. The chart below shows Italy’s year-over-year real GDP growth, with the shaded areas showing when Italy is in recession. Prior to joining the Eurozone, GDP averaged 2.0% (1982-2000). Since joining the Eurozone, GDP growth has fallen to 0.4%. The components of GDP show similar patterns Consumption pre-Eurozone averaged 2.2%; post-Eurozone, it is 1.0%. Government spending averaged 1.4% pre-Eurozone; post-Eurozone, the average is 0.6%. Investment averaged 1.8% pre-Eurozone; post-Eurozone, the average has fallen by 0.2%.

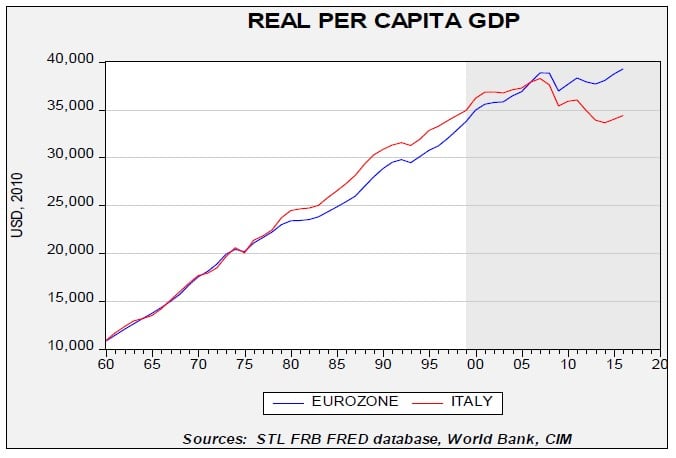

Finally, real per capita GDP has been declining since the Financial Crisis.

The shaded area represents the period since the introduction of the Eurozone. Real per capita GDP for Italy is now lower than when the euro was formally introduced.

These charts show that Italy’s economy isn’t functioning well under the current structure of the Eurozone. The fixing of the exchange rate and restrictions on fiscal spending have weighed heavily on the Italian economy. Although the above charts make it clear that Italy would probably be better off if it had never joined the single currency, politically, Italy did not want to be left out of the major project of European unity.

It should be remembered that the Eurozone was not just an economic arrangement. EU leaders realized that nationalism would never be fully overcome, but their hope was that closer economic unity would act as a substitute for political unity. Europe had been “ground zero” for two world wars and EU leaders didn’t want that to happen again. So, the progression from the European Coal and Steel Community in the 1950s to the Economic and Monetary Union that created the Eurozone and the single currency were all done to foster unity and prevent another European war. Accordingly, nations entered the Eurozone not just for economic reasons but for political ones as well.

Part II

In two weeks, we will analyze the upcoming elections, discuss German influence on the EU and conclude with potential market

ramifications.

Article by Bill O’Grady of Confluence Investment Management