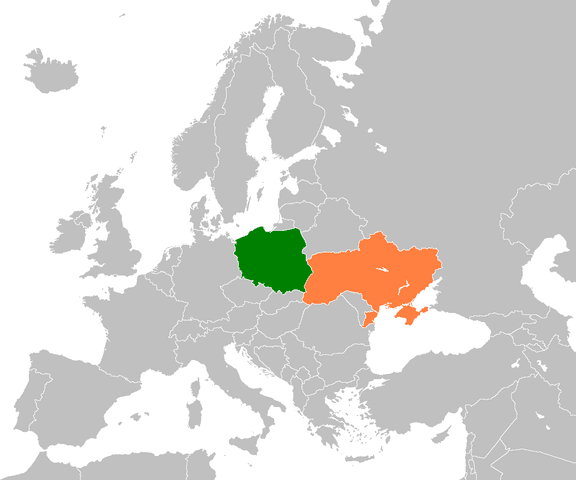

Poles and Ukrainians have every reason to hate each other, but they don’t. Quite the contrary, despite unsettled historical matters, the way these two big nations interact might serve as an example of peaceful, voluntary cooperation. And the market is playing a substantial role in the improvement of their relations.

The Dark Period of the Polish-Ukrainian History

Unlike Poland, Ukrainians didn’t enjoy a stable independence between the world wars. Although they managed to create two de facto independent states shortly after WWI, they didn’t exist for very long. The Ukrainian People’s Republic (1918-1920) was defeated by Bolsheviks, the West Ukrainian People’s Republic (1918-1919) by Poles. As a result, four to five million Ukrainians were living in Poland during the interwar period.

The leaders responsible for the massacre are still considered heroes among some parts of Ukrainian society.

The policy of Polish authorities towards the Ukrainian minority was harsh. Organizations supporting the independence or autonomy of Ukraine were frequently repressed, their supporters arrested, lashed, or — as Ukrainian sources state — killed during punitive actions against the young nationalist movement. Tensions were rising, but the Polish government effectively nipped all potentially aggressive actions in the bud — that is, until the Second World War broke out.

In 1943, when both Polish and Ukrainian people were under the occupation of Nazi Germany, Ukrainian nationalist fighters from the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), together with regular Ukrainian villagers, brutally murdered up to Brutally murdered 100,000 Poles in the regions of Volhynia and East Galicia.

As historian Grzegorz Motyka has stated, the purpose of this action was to cleanse the Western Ukraine territories of the Polish nationals in the hope of creating an ethnically clean Ukrainian state after the war. What makes the history of both nations even more problematic is that the leaders responsible for orchestrating the massacre of Polish people are still considered heroes among some parts of Ukrainian society as they also played an important role in fighting against the brutal Soviet regime in Ukraine.

In 1947, two years after establishing the communist state of Poland, Poles executed the “Operation Vistula” — forcefully exiling over 140,000 Ukrainian nationals from the southeastern parts of the country. The authorities justified it as a revenge act for the Ukrainian atrocities from several years before — but the exiled Ukrainian people had nothing to do with the crimes described above as they lived in a different region.

One can hardly imagine how two such nations could cooperate.

As journalist Pawel Smoleński writes, the operation was aimed at the “final solution of the Ukrainian question in Poland.” Professor Jan Pisuliński adds that it bears signs of a crime against humanity, as people were deported against their will, often badly beaten or even tortured.

Ukrainians Are Saving the Polish Economy

One can hardly imagine how two such nations could cooperate. Yet, as the past three years have shown, regular Poles and Ukrainians not only maintain friendly relations, they depend on each other. Their example is a perfect illustration of a simple economic principle: you will not harm your fellow human being if you can do business with them.

And that's basically what happens in that region nowadays. Poland has always been quite a popular destination among Ukrainians, being the closest and the most easily accessible EU country for them. After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014, the levels of Ukrainian migration to Poland skyrocketed. According to the data of the Personnel Service quoted in this Polish article, there are around 900,000 Ukrainians legally employed in Poland. The author of the article states that next year, we can even expect three million Ukrainian migrants in Poland! That would constitute almost 8 percent of the country’s population.

One could wonder, what on Earth brings them here? After all, in recent years low Polish wages, unemployment, and a high level of bureaucracy made several million Poles emigrate, mostly to the United Kingdom and Germany.

The Polish labor market is heavily dependent on workers from Ukraine.

But the Polish labor market, as adverse as it might be, is still a better option than what Ukrainians have in their own country. The Ukrainian economy, devastated by its war with Russia and the enormous level of corruption it suffers, offers them an average monthly wage of 262 USD, a barely functioning pension and welfare system, paired with little to no opportunities for sustainable employment.

Compared to these stats, Poland, with its astonishing average net monthly wage of 934 USD, seems like a gateway to heaven. Ukrainian workers, bestowed by their Slavic nature with the gift of industriousness and entrepreneurship, finally can truly excel and show their full potential. Ukrainian nannies, builders, drivers, and technicians are able to not only support themselves on a level of living never experienced before but also regularly send money to their families staying in Ukraine.

Ukrainian migration is a deal of mutual interest. As Cezary Kaźmierczak, the chief of the Polish Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers, pointed out, “Without Ukrainians, there would be an absolute catastrophe.” The Polish labor market is heavily dependent on workers from Ukraine, which account for around 5-6 percent of all the employees in Poland. What’s more, the times when Ukrainians took up only the hardest and worst-paying jobs are long gone. Since they are considered to be hardworking and skilled employees, the market has opened more and better-paid opportunities for them.

The Peaceful “Conquest” of an Important Ukrainian City

European borders used to look different before the Second World War — many territories that now belong to Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania used to be part of Poland. As the war ended, Europe’s map was redrawn. As a result of the Yalta Conference, Poland got land in the West from Germany, but the Eastern part of the country — including parts of now-Western Ukraine — was incorporated by the Soviet Union.

Waiters try to endear Polish customers by willfully learning Polish.

One of the major cities in the territories, which Poland lost to USSR, was Lviv, now a million-person city in Ukraine. Lviv, the modern capital of Ukrainian nationalism, has an important place in the Polish national identity as well. In 1920, it became a symbol of the heroism of the Polish soldiers in the war against Ukrainians and, later, against Bolsheviks. The city also gave Poland many illustrious people of science and culture.

This might explain why some people would like to see Lviv as a Polish city again. What they don’t realize is that to make Lviv Polish, you don’t need guns and soldiers. For several years now, this city was and is in the process of being “conquered” by Polish tourists, tempted by both the low prices and high quality of food and accommodation. And Ukrainian people really don’t mind this kind of “invasion.”

Polish visitors are the biggest group of tourists in the city, a substantial source of income for hotels and generous tips for waiters. Needless to say, many waiters try to endear Polish customers by voluntarily learning Polish — which is something you can never achieve by forcefully decreeing people speak a given language.

In any other circumstance, a city with a complicated history like Lviv — considered an important historical symbol for two big European nations — would become a hotspot of nationalist tensions and possibly a source of serious violent conflict. But unlike in the East, where Ukrainians fight in the real war against the real enemy, the only fight that happens on the streets of Lviv is competition for customers.

Making Progress

One honest talk in a pub means more than a thousand political conferences.

It might be true that Polish-Ukrainian relations — especially at the government level — are still far from being perfect. The most burning issue is the place of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in the nation’s history. Ukrainians praise it for fighting against communists, but ignore — or, more probably, aren’t aware of — the anti-Polish crimes committed by the organization.

Such problems can be solved only by dialogue on the political or, more importantly, on the citizen level. And there has never been a better opportunity for discussion than now. Whether politicians like it or not, Poland remains the most important representative of Ukraine in the European Union. Poland provides jobs for Ukrainians who, in exchange, prevent the Polish economy from going down the drain. And let’s not forget who is fighting for Europe’s — and Poland’s — security on the frontlines of Donbass.

We owe each other a lot more than we think. It is crucial to bear that in mind when discussing our differences. And remember — one honest talk in the pub down the road means more than a thousand political conferences.

Paweł Piwowar

Paweł Piwowar is a passionate advocate of economic and individual liberty from Poland, cooperating with two NGOs as a filmmaker and project manager. He is currently pursuing his career in journalism and digital news media.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.