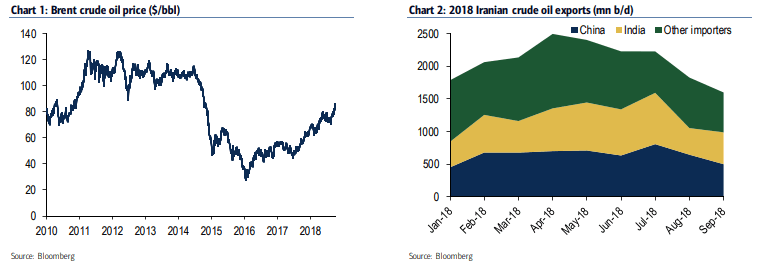

Over the past 12 months, the price of oil has been on a tear. After bottoming at a low of around $30 per barrel towards the end of 2016, Brent has since recovered to trade above $80, up more than $20 a barrel year-on-year.

Rising prices have been a boon for oil investors. The industry has seen profits surge off the back of the oil price recovery. Rising prices have only been part of the equation. Over the past five years, oil companies have rushed to slash prices to cope with the oil price downturn. Companies are now benefiting from the double tailwind of rising prices and lower costs, resulting in fatter profit margins.

But while oil companies and their investors are celebrating the oil price recovery, economists are starting to become concerned about the impact higher prices might have on the global economy.

Q3 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

A global slowdown

A recent report Bank of America Merrill Lynch's global economists, Aditya Bhave and Ethan S. Harris considers the impacts $100/bbl oil might have on global economic growth and the winners/losers from such a scenario unfolding.

But first, the report asks if $100/bbl oil is a realistic prospect?

The most critical near-term driver of oil prices is the possible supply shock coming out of Iran. Last year, Iran exported more than 2.1 million barrels of oil per day. The current US administration wants to get this down to zero through sanctions on US companies that will force other countries to cut their imports of Iranian oil. China and India account for nearly 60% of Iranian oil exports, and while India has shown its willingness to comply with sanctions, China has substantial room to increase its purchases from Iran possibly at below market prices.

Bhave and Harris believe this is unlikely because the country does not want to further escalation of its trade war with the West:

"Refiners from Europe, Korea, Japan and India have already cut their purchases from Iran, and exports have fallen by 900mn b/d in the last five months. This leaves China with substantial room to increase its purchases from Iran, possibly at below market prices. However, doing so would further escalate China’s trade and broader geopolitical conflict with the US administration. Therefore our colleagues in commodities strategy believe China will take a middle course, maintaining its current imports from Iran, defying the sanctions, but not increasing imports. News reports suggest that China is increasing its crude oil imports from West Africa to compensate for import cuts from the US and possibly Iran."

As well as the Iranian supply shock, Bank of America's analysts thinks investors should be watching Venezuela as well. The collapse of Venezuela's economy has sent production down to levels not seen since the 1940s, which along with other factors putting pressure on supply within the global oil market, has resulted in global inventories steadily falling.

Meanwhile, the capacity to increase supply around the world is limited after years of underinvestment. Against this backdrop, higher oil prices "seem inevitable" according to the economics team at BoA.

There are three primary reasons why a higher oil price could be bad for the global economy.

Firstly, "large price moves tend to cause reallocation and uncertainty shocks, which slow growth, particularly in the short run," BoA's report opines. It goes on to say that volatile oil prices make it difficult for businesses to commit to spending decisions that hinge on the price of oil.

Second, the report notes that "purchases of oil typically have a larger marginal propensity to spend than producers." As a result, any significant increase in oil prices may cause consumers to reduce their purchases of goods and services that are both the linked and not linked to the price of oil. On the other side of the equation, oil producers would see windfall profits if oil traded back above $100/bbl, which could drive additional capital spending wage hikes. However, the report notes that because "owners of public and private companies tend to be disproportionately wealthy" they have lower marginal propensities to consume, and may simply save rather than spend profits.

Third, countries that stand to lose a lot from higher oil prices have historically been much more systemically crucial to the global economy.

The biggest losers from higher oil prices are likely to be the Euro area, the UK and Japan:

"As discussed above, many of the large economies including the Euro area, the UK and Japan would be clear losers because they are oil importers. We estimate that growth in these countries would be depressed by 0.2-0.5pp next year. The impact in Japan is likely to be in the low end of this range because robust recent income growth has shored up household finances. By contrast in the Euro area and the UK, saving rates are already very low, leaving households without much buffer to smooth through the impact of a large oil shock."

In comparison, the surge in shale oil production has left the US in a better position to handle the oil market shock than in the past. The same appears to be true for Australia where a recent ramp up in LNG production means higher oil prices will "now have a positive impact on terms of trade."

Overall, Bhave and Harris believe $100/bbl could take two tens off global growth in 2019 -- not a significant impact overall, but considering where the hammer will fall hardest (EU and UK), the knock-on effects could be substantial.

This article originally appeared on ValueWalk Premium